Color Story

I watch a lot of Project Runway. Entering into the fashion world through the shattered vision of reality TV, I get to critique the efforts of fledgling fashionistas. The viewers are asked to forgo their logic for the greater good of fashion. Forget that the designers sew garments out of cell phone cases. Ignore the fact that the judges seriously evaluate hot pants made from SweeTarts. The absurdity provides me with no end of glee. “Think about the story of the woman you are designing for,” the judges remind the designers. “Who is she? Where is she going?”

I watch a lot of Project Runway. Entering into the fashion world through the shattered vision of reality TV, I get to critique the efforts of fledgling fashionistas. The viewers are asked to forgo their logic for the greater good of fashion. Forget that the designers sew garments out of cell phone cases. Ignore the fact that the judges seriously evaluate hot pants made from SweeTarts. The absurdity provides me with no end of glee. “Think about the story of the woman you are designing for,” the judges remind the designers. “Who is she? Where is she going?”

Viewers equipped with insider jargon can pretend, for 43 minutes, that we are experts on fashion, too. Ellie, my twelve-year-old, and I often predict what Nina Garcia will say about a particular outfit. “I love your use of color blocking. Very couture.” We pretend to be Michael Kors. “I love the balance of hard and soft at play between the tulle and barbwire.” Often, our fake comments include the phrase “color story,” because Tim Gun says it so often.

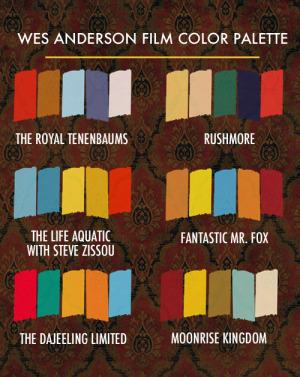

We mock that last phrase, yet it seems there is something to it. What is a color story and why does having one matter? In the fashion world, just like in the movie industry, the color story is what the artist’s particular palette conveys. The success of any piece of art — whether a garment, a painting, or a film — is often in direct proportion to the color choices.

In his philosophy of aesthetics, Plato determined that beauty incorporates proportion, harmony, and unity. Later, Aristotle added his two cents that beauty included the universality of three elements: order, symmetry, and definiteness. A great example of this is found in the beauty of Wes Anderson movies.

For Wes Anderson, the color story is clearly a high priority, for the colors he uses are consistently direct, determined, and definite. Fans of Wes Anderson movies may find themselves, upon glancing at the color palette of all of his films, delivered back to the emotional story of each movie. The effect of the color story in Moonrise Kingdom is no exception.

In one scene, the mother in Moonrise Kingdom, played by Frances McDermott, is standing in a kitchen, calling her daughter to dinner. Her celadon-blue dress and beige sweater mimic the blue and beige above and below the chair rail on the kitchen walls. Why does this delight me to no end? This is not a throwaway detail; it is a burst of life-affirming imagination. It must be the symmetry and order about which Aristotle spoke. Though the mother was an attorney, she was connected, through color, to the kitchen and the 60s ideal of a woman and mother.

In one scene, the mother in Moonrise Kingdom, played by Frances McDermott, is standing in a kitchen, calling her daughter to dinner. Her celadon-blue dress and beige sweater mimic the blue and beige above and below the chair rail on the kitchen walls. Why does this delight me to no end? This is not a throwaway detail; it is a burst of life-affirming imagination. It must be the symmetry and order about which Aristotle spoke. Though the mother was an attorney, she was connected, through color, to the kitchen and the 60s ideal of a woman and mother.

“The color palette of a film is the canvas on which the look of the film is drawn,” says Stockhausen, one of the production designers of Moonrise Kingdom. “Color, next to music, is probably the thing that affects the audience the most, and the choices of dark, light, bright, or pastel color schemes create an indelible feeling in them. It is important, therefore, that we as filmmakers be in control of how that feeling is created.”

In trying to further understand my enjoyment of the color treatment in Moonrise Kingdom, I went to an essay entitled “Recovering Goodness, Beauty and Truth” by Andrew Fellows. “The human imagination has this ability to read symbols — a word, picture, gesture, sound, shape [color?] . . . These symbols point beyond themselves to a higher reality; it is by means of them that reality becomes meaningful for us. We cannot have a firsthand experience of something until it is symbolized to us.”

“Through beauty,” Fellows surmises, “we are led to a joy which belongs to another world.” Walking out of the theater after viewing Moonrise Kingdom, I carried with me the joy of a determined color story. Anderson’s choice of warm, desaturated colors intensified a feeling of nostalgia for childhood. Every shot is elaborately self-conscious recreating a childhood longing for fantasy worlds. The real genius of Wes Anderson, in my opinion, is his story of color.

Nostalgia and Norman Rockwell

"All Together" by Norman RockwellWho else calls up a longing for a time gone by more than Norman Rockwell? In his paintings, the best of the 50s and 60s have been captured in the muted yellows, khakis, and celadon blues. Images of ice cream parlors, soda and barber shops, and troops of boy scouts led by patriotic and capable scout masters trigger a yearning for a simpler time.

"All Together" by Norman RockwellWho else calls up a longing for a time gone by more than Norman Rockwell? In his paintings, the best of the 50s and 60s have been captured in the muted yellows, khakis, and celadon blues. Images of ice cream parlors, soda and barber shops, and troops of boy scouts led by patriotic and capable scout masters trigger a yearning for a simpler time.

As I watched Moonrise Kingdom, I immediately recognized the Norman Rockwell influence. The stills from the film looked like paintings I’d seen before. I swore to myself they were replicas of Saturday Evening Post covers. They weren’t. But Norman Rockwell’s paintings did affect the design of Moonrise Kingdom.

“Norman Rockwell’s Boy Scout paintings were inspirational,” says Stockhausen. There is something life-giving in recognizing one artist’s influence on another. I see what you did there, we say to ourselves. The artist, by reflecting another’s work, offers the viewer a personal invitation to enter the story as a participant. Many viewers may have connections to the scout paintings of Norman Rockwell — even if they didn’t live in that era themselves — to memories of mid-century juvenile fiction, to playing Parcheesi in the parlor, to finding solace in a record player on a rainy day.

What’s in Suzy’s Suitcase?

When my husband and I were at our wits’ end parenting our precocious five-year-old, we took her to see an art therapist, a classmate’s mother, who specialized in children. As part of our intake and assessment, she gave us the task of creating a collaborative art piece. Together, we were to draw a deserted island and place ourselves there along with two survival items per family member. We were also allowed to draw natural resources that we’d need for survival.

As she timed us, I frantically began drawing myself with my survival items: a fishing pole and a machete. Then I was off to the races adding palm trees resplendent with coconuts and palm fronds, banana trees, birds flying overhead, and schools of fish. As the therapist began to count down to the end of our project, I looked up to see Dave, my husband, working on a detailed rendition of a lobster.

“What are you doing?” I breathed in exasperation. “She said survival items, not luxury items!”

“Time’s up!” the therapist called to us.

While we placed the caps back on our markers, the therapist asked us to each share what we’d drawn. Our five-year-old, sharing first, had completed a stick figure of herself along with a suitcase full of clothing that she explained was “only for my clothes and nobody else’s.” I went next, proudly explaining how efficiently I’d used my time to provide our family with all the necessary resources for a secure existence on a secluded island. Finally, Dave shared his contribution: a guitar, the complete works of C.S. Lewis (the book he’d drawn had a lion on the cover), and a sketch of his pants rolled up wading in the water toward a skillfully depicted lobster.

The therapist applauded our efforts and determined that we, as a family, came up with more than enough to survive, and therefore, in her therapeutic opinion, were doing just fine.

I, on the other hand, was not so sure. In my un-therapeutic opinion, we had utterly failed. During the car ride home, I noted our failures:

1. None of us drew our one-year-old in the picture until the therapist noted his absence before our time ran out. What healthy mother forgets her own child, I ask you?

2. For the half-hour of activity, we did not speak at all. We left our five-year-old to her own devices, thus allowing a monster of self-absorption to flourish, and a vain one at that! A suitcase full of clothes? Really?

3. Casting hand-woven nets over schools of feeder fish, I was alone in the role as provider while Dave was off making music, reading books, and enjoying the sweet life with broiled shellfish and afternoon wades in the water. When do I get to swim?

Even though I could acknowledge the absurdity of whining about how tired I was in our fantasy world, my diagnosis was clear: we had a work-share imbalance in our marriage. For seven years, I have stubbornly clung to this diagnosis. Until watching Moonrise Kingdom.

In the movie, two young lovers set out to inhabit their own deserted beach. Both Sam and Suzy bring a collection of items they determine indispensable for their survival. When Sam — who brought along everything a good scout is prepared with — pressed her to share what was in her suitcase for cataloging purposes, Suzy methodically laid out her contributions: a record player, records, books, and binoculars. As she finished placing her items on a large rock, I thought for sure he’d let her have it. But how did that prepubescent kid handle such a disparity in the responsibility of sharing? The answer: better than me.

In subsequent scenes, we find the pair of runaways reading the afternoon away and listening to the vinyl records Suzy brought. Their emotional survival depended on Suzy’s baggage. Sam’s fire-making skills and compass literacy were necessary for sure, but Suzy’s contributions were equally valuable. Why did their mismatched relationship work? I’d have to say, in my un-therapeutic opinion, that it was their ability to accept what each brought to the island without judgment.

* * *

I know that Wes Anderson movies are not everybody’s cup of tea. I can imagine my friend Sonia’s response: I got it. I just didn’t like it. However, if you watch Moonrise Kingdom, you might be surprised by the memories and emotions evoked by the story of color, the nostalgia of Norman Rockwell, and the contents of Suzy’s suitcase. I left the theater affected not so much by the plot line as by the gravitational pull of the film’s images and color. For me, Moonrise Kingdom brought an unexplainable joy that just might belong to another world.

A recipient of a master’s degree in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts, Sarah Braud is a freelance writer and artist living in Franklin, Tennessee, with her husband, photographer David Braud, and their two children, Ellie and Atticus. Sarah’s writing has not been published in several literary journals, though her collection of rejection letters is compounding into forceable proof of a solid writing career.