Man gave names to all the animals

in the beginning, a long time ago.

—Bob Dylan, “Man Gave Names to All the Animals” from Slow Train Coming

He saw that in this dusty and fathomless matter of learning the true name of each place, thing, and being, the power he wanted lay like a jewel at the bottom of a dry well. For magic consists in this, the true naming of a thing.

—Ursula Le Guin, A Wizard of Earthsea

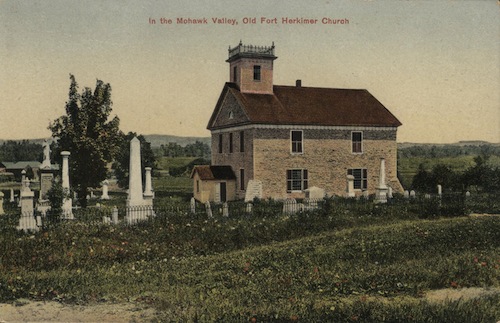

On June 16, 1710, a ship dubbed The James and Elizabeth completed its trip from London to New York. Among the passengers were Johann Adam Baumann (age 44), his wife Susanna Catharina (Dresch) Baumann (age unknown), and their six children: Margretha Elisabeth (20), Anna Margretha (17), Elisabetha Catharina (15), Heinrich Peter (11), Maria Sybilla (9), and Maria Margretha (7). Several years later, Baumann and a small group of fellow Palatine immigrants became the first Europeans to live on the Mohawk River in a deal known as the Burnetsfield Patent.

A map still exists in which I can see the precise parcel my ancestors farmed in the town where, three hundred years later, I grew up knowing nothing of the history of my family or its name.

I knew only my own small story — mostly, that we were poor and I hated it. When the school bus picked me up, I felt ashamed, as the house was always in a state of disrepair. After buying a cheaply refurbished double-wide trailer on a country road, my parents took out a loan they couldn’t afford to dig a foundation and build a small addition off the back. That house was the focal point that I most associated with the name Bowman, since the place — and the way we lived — was available for all to see.

I was eight years old when the construction started, and the project never saw completion. Outside and in, things were left undone, half-finished, or simply broken. My parents always ran out of money long before they could make good on whatever part of the project they’d started. (Worse, they always fought about not having money.)

The new cellar they’d built retained far too much water and had no sump pump, encouraging constant dampness and the growth of mold that would put me in the hospital with asthma attacks. Silver foam board alone covered the exterior of the house for many years. It weathered to an unbearably lonely gray. The bright orange company logo repeated dozens of times on every board dulled to something like the dirty and burnt yellow of an old paperback. I longed for the traditional white clapboards or the tidy new vinyl siding on neighbors’ houses, complete with soffit and aluminum flashing.

Our roof awaited asphalt shingles with only thin layers of tar paper that would come up and flap when the wind got under them. The floor in the main part of the house was uncovered chipboard, nails and all; it was the first thing you saw when you walked in, and it had holes in it. The cabinetry in the kitchen had been pulled out in hopes of a complete remodel. Instead, the plumbing simply remained visible and the sorts of things that normally go under one’s sink were placed elsewhere.

I’m not sure if I ever felt truly settled in that house. Everyone always spoke about “someday” when they could finally get this or that done, and how, on that day, everything would change. But nothing did. (I’ve told a little more of my family’s story here.)

After my mother left my father in 2006, neither of them could afford the mortgage payments on the old house. It was repossessed by the bank, which finally dumped it at a fire sale price not even equal to the total amount of the home improvement loan my parents took out in the mid-1980s.

As an introverted child embarrassed by our circumstances — by our very name — I turned to the woods. I climbed trees and sat in the crooks of branches daydreaming of a better life for hours at a time. I dug up arrowheads of the original settlers, built forts, swam in Tory Creek, and spent the winter tunneling through the wild drifts of snow. Most of my positive family memories, too, are outdoors. We chopped and stacked enormous amounts of wood to prepare for winter. We gathered seasoned kindling at the edges of the woods. We dug ditches to try to reroute the water off the hills around our house and dirty gravel driveway; we built up the bank on the road side with the root systems of native pines. We grew tomatoes. We ran around the field at my grandparents and ate from the apple tree and plum tree. We swam in Canadarago Lake; we fished the Erie Canal and the Mohawk River. We did nothing special, but we did it outside, and I liked that best.

Even so, when I think of growing up in the Bowman house, I think about how the Bowman name was one I would’ve traded in a heartbeat for the proud names of families who lived on Brookside Drive in those lovely split-level homes, or those who owned extensive property in the country and had three-wheelers and swimming pools you couldn’t see from the road, or those who went on vacation to Disney World and other magical places I hadn’t seen and probably never would.

It could not have occurred to me that perhaps with some context, that perhaps with more stories to understand the heritage of my name, I might have felt more connected to it. Maybe I could have accepted it and even come to learn to celebrate it.

What’s in a name, after all?

Juliet’s soliloquy is quoted (and misquoted) every year around the world as Shakespeare’s play continues to be popular with both theatergoers and junior high school English teachers. But do those teachers try to answer her question? I vaguely recall something mine said about the connection between name and identity, and about identity and story.

My family’s name, Bowman, derives, I have since learned, from the German “Baumann.” The Surname Database says, “This long-established surname is of early medieval German origin, and is either a status name for a [subsistence] farmer or a nickname meaning “neighbour, fellow citizen.” Another source notes that the name has its roots in the Middle High and Old German word ‘baum’ or “boum,” meaning “tree.”

I’ve come to love the earthy resonance of both etymologies. We have indeed been citizens living in the woods by the trees, first on the banks of Germany’s Rhine and then New York’s Mohawk River. But how did we come by our citizenship? What’s in a name?

Johann Baumann and Susanna Dresch, the only daughter of a shoemaker, married in Bacharach, Germany, in February 1688, and undertook a difficult life together. Their native Palatinate region endured destruction and pillaging from the constant wars waged by the Swedes, the French, the Saxons, and other neighbors. Whichever prince claimed dominion over the area inevitably raised taxes, squeezing every last penny from the Palatines, until the land was wrested from him by the next war. The residents became known throughout Europe as “the poor Palatines,” one of the humblest and least desirable people groups in the Western world.

Then came the legendary winter of 1709, the coldest on record, later called “The Year Europe Froze.” Those who had anything left lost it: the grain froze, the livestock froze, people froze to death in their beds at night despite building roaring fires before going to sleep. It was said that birds froze in midflight. The city of Paris alone reported a death count of over 24,000. Across Europe the lack of food and drink caused famine and rioting, especially among the lower classes. As is always the case, the brutal winter hit the very poor the hardest. The Baumanns and their neighbors were among that group. This should have been the end of the story for them, as it was for so many thousands just like them. But somehow, the Baumanns survived.

Meanwhile Europe was at a loss in terms of what to do with the miserable hangers-on in Germany. Their dire situation could no longer be ignored, and Queen Anne of England had an idea. Her colonies in Carolina had been producing pitch from the abundant pine trees to be used by the Royal Navy. She would ship the Palatines to the New World, and in order to allow them to pay off their passage, she would put them to work, making more pitch. A pre-Twitter and pre-Facebook master of marketing, she began a campaign, sending her underlings everywhere Palatines remained to begin rumors and disperse books with her picture on the cover and the title page in gold letters. The books detailed the attractions of the “Island of Carolina” — foremost being the availability of good farming land and freedom from the invaders that had been the Palatines’ lot for over a century. Buzz about The Golden Book infiltrated the starving Palatinate, encouraging families to leave behind their shambles of homesteads and strike out for the colonies. I can only imagine the combination of excitement and fear Johann and Susanna felt when hearing about this magical place and considering the prospect of leaving their homeland for a new life across the great ocean.

The journey began when the ships arrived to carry the Palatines down the Rhine to the Dutch city of Rotterdam. This was a four- to six-week trip fraught with danger, malnutrition, and disease, and some died before the first leg of the trip was completed. The rest camped outside Rotterdam upon arrival—the city could not support them — and stayed for several more weeks. It was still winter, and the Palatine castoffs were living in “shacks covered with reeds,” according to Palatine scholar Henry Jones Jr. The death tolls continued to climb within the refugee camp.

Survivors eventually sailed on from Holland to London, where they were once again forced to camp outside the city proper. The fortunate received government-issued tents. Even if they survived the elements, however, they were not out of danger: the British citizenry resented their presence and its perceived draw on the city’s resources, and after several weeks, the poorest Londoners formed a mob and attacked the refuges with axes, hammers, scythes, and other weapons, killing some and wounding others. The Palatines had nothing with which to fight back. How did Johann and Susanna Baumann protect themselves and their children? How did they survive yet again?

The Queen had to act quickly, for by then she had become a victim of her own PR blitz. Her first action was, in fact, to send some of the ships back to Holland. And Holland sent them back to Germany! Other Palatines were dispatched to Ireland and various parts of the United Kingdom. The original plan was beginning to look disastrous.

Of the 30,000 Palatines who initially left the region for Holland, only about 13,000 made it to England, and only an estimated one-fourth of these ragged and sickly ones finally set sail for America. More bad news, of course: for the long transatlantic journey, they were packed tightly into small, unsanitary ships infested with vermin. Many became ill and died. Then the entire fleet was ravaged by “ship fever,” now called typhus. Many more died.

Yet the day would come when some of these Palatines would actually see the shores of the New World. Even with that miraculous arrival, though, life would not get any easier. The British officials had no idea what to do with 2,500 disease-laden German-speaking newcomers. At first they demanded that the immigrants camp on an island off the shore of New York City (typhus was still claiming victims for some time after the landing). But finally they had no choice but to accept them. They relocated them up the Hudson River, and put the healthy ones to work as best they could, making it clear that their status as indentured servants would continue for years to come. They also broke up families, put children to work, and generally ran the operation very badly. To boot, the British didn’t understand until then that the northern pines of upstate New York were characteristically different from the pines in Carolina; the New York varieties were, in fact, worthless for the production of pitch. Suddenly, there was not enough work to keep the Palatines busy and profit the crown.

Some Palatines staged a revolt, demanding to be free and to receive the land they had been promised from the days of The Golden Book. The revolts were put down. Back in England, the Tories won control of Parliament from the Whigs, who’d sponsored the Palatine relocation. The newly-empowered Tories pulled financial backing from the project they had never agreed with in the first place. The British officials in the colonies were left to deal with the problem of the Palatines on their own. Their government at home offered no support and seemed even to have little interest in the results.

At that point, many Palatine families simply got up and walked away. There was little anyone could do to stop them. Many went back to New York City, most others to Pennsylvania. Some actually returned to Germany. A small band of forty or so families ventured out into the untamed wilderness further up the Hudson and west to the shores of the Mohawk River. Johann and Susanna Baumann and their children were one of these families. This decision to go west and start over would profoundly shape my own life three hundred years later.

The British government tried to discourage the deserters by not allowing them to take any government-owned tools and implements they would need to clear and farm the land. They went anyway. And they devised their own tools out of whatever was available. Again quoting scholar Henry Jones Jr., the records show Palatines using tree branches as pitchforks, hollowed-out log ends as shovels, and large knotted pieces of wood as mauls.

Trees. Baumann: “Man of the trees.” Citizens, neighbors working the earth together.

This is no rags-to-riches myth; it’s just a story of hard work and plain grit, and relationship. It is worth adding that the Palatines who settled on the Mohawk River lived in peace with the Indians who were instrumental in helping the Palatines survive their first cold winters on their own.

* * *

In The Power of Naming, author J.B. Cheaney writes:

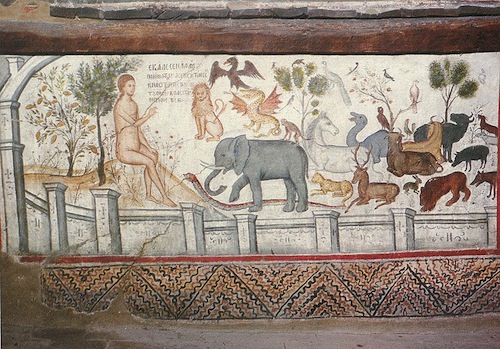

Notice how quickly Adam progresses. From pointing and saying "elephant," he bursts into poetry when confronted with a creature like himself: "This indeed is bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh. She shall be called Woman because she was taken out of man." He's speaking not only conceptually but metaphorically. He's making a clear logical connection, a valid comparison. He's not just talking; he's understanding. And creating: Out of a cloud of words steps a relationship.

The name of the game for the Palatines was survival, and the Baumanns were survivors. They became citizens, doing nothing extraordinary except staying alive. And they were inventive and infinitely industrious in their survival. What’s in a name? A story — one of overcoming hardships in pursuit of a better life for your children in the face of outrageous odds that claimed the lives of friends and relations at every step. This immigrant story deeply informs the story that I grew up with — a story where my very name, rightly or wrongly, was a source of shame to me.

To know who my family is, to know who I am, I needed to know the power of our name; I needed to know the story of the Palatine immigration to New York, the tale of the Baumanns enduring during some of the more difficult circumstances any people group on earth had ever faced. A quick summary would not have sparked my compassion — would not have caused me to imagine my ancestors for any length of time — for any more than a passing moment of intellectual curiosity. Story holds metaphor, and metaphor enables the creation of a bond. Adam names the animals with wonderful aplomb, but when he names his partner, he reorients himself as well. His name stays the same but its meaning changes in some foundational way. There’s a story now, a very old one, that still moves us today: a story of how men and women relate to one another and make their way through the world together. As J.B. Cheaney says, “Out of a cloud of words steps a relationship.” Name is related to identity, and identity comes in part from story. When I learned more of our stories, I could see my family and myself in a new, larger context; I could enter into relationship — into community — with both the quick and the dead; I could inhabit a richer understanding of what community means. I could even “burst into poetry” and celebrate my heritage, my name.

“Adam Naming the Animals,” a 16th century wall painting at the Agios Nikolaos Anapafsas Monastery in Greece.

“Adam Naming the Animals,” a 16th century wall painting at the Agios Nikolaos Anapafsas Monastery in Greece.

In his essay “Naming and Being,” Walker Percy speaks to the role of the namer in making us “co-celebrants of being.” He says, “When a tribesman utters a single word which means the-sun-shining-through-a-hole-in-the-clouds-in-a-certain-way, he is combining the offices of poet and scientist. His fellow tribesmen know what he means. We have no word for it because we have long since analyzed the situation into its component elements. But we need to have a word for it, and it is the office of the poet to give us a word. If he is a good poet and names something which we secretly and privately know but have not named, we rejoice at the naming and say, ‘Yes! I know what you mean!’ Once again we are co-celebrants of being.”

I had analyzed my childhood “into its component elements,” only seeing it from my limited perspective. When I learned the Palatine story, I could celebrate. I’d been named again, with a fuller, more ancient name. And by newly addressing the question “What’s in a name?” the Palatine narrative was a way for me to begin addressing that other question, which forever lurks below the surface of a name: “Who am I?” The first question belongs to Juliet; she must know about the power of a name in relation to someone she loves. The second question belongs to Oedipus; he must find out the true nature of his being. “How did my family survive?” is a poignant and interesting inquiry for me, in part because it’s a starting point to answering, “How will I go on?” I will need many more stories in order to continue answering that question, stories and poems and songs and essays the language of which reflect my humanity back to me across time periods and cultures. I will need new words and, finally, a new name.

In Biblical terms, a new name signifies a change in direction, a turning away from one thing and a turning toward another. Lisa Nichols Hickman reminds us that “God called Abram and Jacob and then named them Abraham and Israel — their names marking a dramatic shift in life’s trajectory, a new orientation, a new mission, a new way of life bound in faith to the God who named them.” Other examples abound.

In the Book of Revelation, God promises that, “To him who overcomes, I will give some of the hidden manna. I will also give him a white stone with a new name written on it, known only to him who receives it.” That’s a substantial promise, a name infinitely more meaningful than Bowman, a fulfillment, perhaps, of my first name Daniel, a Hebrew name that means “God is my judge.” But what is the judgment?

A name is always a kind of judgment; everyone who learns it will call the named one thing and conceive of the named as a certain kind of thing, as I did when I was growing up with the negative implications of my name. Something is always lost in that transaction, in part because the name cannot contain all the stories that make the named one everything he or she really is — the True Name — how God sees each of us. A name from God, “known only to him who receives it” is a strange and thrilling prospect. Perhaps whatever’s on that white stone will change what it means to ask “What’s in a name?” and two of the significant questions it contains: “Who are we?” and “Who am I?”

Until then, I am doing what I can to redefine my earthly name, the only one I have, for myself and for my own children who will live in this world as Bowmans. I was among the first people in my family to complete a college degree. I went on to do an MA and an MFA, which makes me the most educated person in the entire long family line. I am now a college professor. In early 2012, I published my first book with a small press in Chicago. I sit on the Board of Directors for a local center that offers music, art, and creative writing instruction to members of our community.

I’m trying very hard to create these new redemptive stories so my daughter and my son can grow up with a different understanding of what it means to be a Bowman, a citizen and neighbor, so that our house will feel like home, and so that story and identity can come together in helpful and generative ways for them. But I’m also doing the work of learning and telling the old family stories, not as a before to which there’s a better after, but as a steady continuum that brings the generations together, a dynamic force that helps us know our true name.

Note: I owe most of my information on the Palatine migration, including my family genealogy, to Henry Jones Jr.’s comprehensive The Palatine Families of New York 1710 (two-volume set). California: Universal City, 1985.

Daniel Bowman Jr. is the author of A Plum Tree in Leatherstocking Country (Virtual Artists Collective, 2012). A native of the Mohawk Valley in upstate New York, he holds an MA in Comparative Literature from the University of Cincinnati and an MFA in poetry at Seattle Pacific University. His work has appeared in The Adirondack Review, American Poetry Journal, Books & Culture, Good Letters, The Midwest Quarterly, Rio Grande Review, Seneca Review, and many others. He recently completed his first novel, Beggars in Heaven. He lives with his wife, Bethany, and their two children in Indiana, where he teaches at Taylor University.