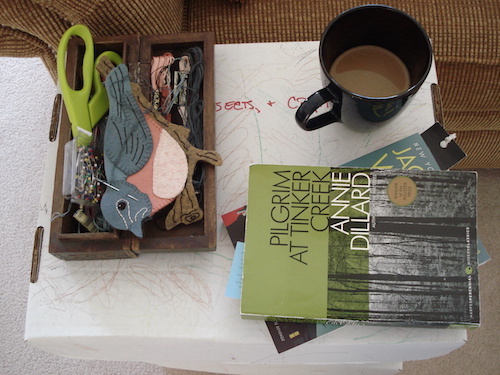

Photograph by Amanda Dymacek

Photograph by Amanda Dymacek

“You see the homes where the windows and doors match each other?” My friend points out the quilt squares as she lays them out, side-by-side, each one pieced to look like a house. “That means the door is open. Those are the squares I stitched on days company came.” She picks up one of the little fabric houses and rubs her thumb across the gold window, the gold door. “It was usually a day when our community group came over.”

I don’t machine sew, but my friend Amanda does. She also knits; I embroider wool felt with needle and thread. When she came to visit me at our new house, it was the first time we had seen each other in six years. Then, we were in a community group together at a church in a different town. She and her husband were one year from moving away. My husband and I — no children yet — were less than a year into living in Blacksburg, Virginia, the town we’ve stayed in the longest, the one we just moved away from. Amanda and I liked each other just fine during that short time we lived in the same place, but it was the intervening years and the Instagram pictures and the periodic status updates on Facebook — “Rainy day, working on my quilt.” And “Snow flurries out my window, a good day for stitching ornaments.” — that told us how much we had in common.

As of last summer, Amanda and I live only one hour apart, and one October weekday, she drove from Farmville, Virginia, to Lynchburg to see me. She brought fingerless gloves to show me; I had packaged up hand-stitched ornaments, a partridge and a pear, to share, and a jar of granola. She confirmed what color I’d like my own pair of gloves to be (light salmon). I showed her my great-grandmother’s quilt draped across my bed. “I don’t put the baby on it,” I explained, “because I don’t want to have to wash it.” I showed her a hole in the middle where the fabric is torn and disintegrating, and earlier today, she messaged me pictures of 1930s reproduction fabrics that might patch it nicely. “This quilt is in great condition,” she told me last week, and I felt a twinge of guilt over using it on my bed. Still, I keep it out. Otherwise, why have it? “It’s definitely from the 30s,” she explained, pointing out certain greens — my favorite colors on the blanket — that you could only get then, not now. I showed her which squares I liked best, mostly tiny flower prints, the ones I wish I could wear in a shirt or a dress.

Amanda quilts both ways: by machine and by hand. I don’t quilt at all, but I can stitch up a storm, especially in autumn. A friend I left behind in Blacksburg pieced a quilt for me last year, the top an orderly arrangement of blue and green squares. It was for my daughter, but, as most stitching projects go, my girl is too old now to stay still on a quilt, and the friend started growing a baby of her own mid-project, and the quilt waited and waited, until one happy day, it arrived in my mailbox with batting and backing all ready, and now Amanda will teach me to stitch it by hand. How many Netflix shows will I watch while I finish it? Which ones? Sermons online serve the purpose, too — in some ways better. The colors on the baby quilt match my bedroom in our new house, and if it’s finished by next winter, it will probably stay up here with me instead, cozy across my own lap, and my daughter will never know it was supposed to be keeping her warm. She has plenty of afghans anyway, made by great aunts and one great-great aunt and also a friend of my mom’s whom my girl has never met (who once gave me her dining table to use in my first college apartment) and by someone else from a past church community whom I never met. She’ll be warm enough.

When I stitch my little felt ornaments, my fingers sometimes get sore. I take breaks and rub them, looking out the window and listening to the sermon that is streaming. “It is perhaps through the work of kind welcome and laden table and warm bed,” the pastor says, “that the church labors most effectively to bear witness to the reality of the kingdom of God and the welcome that we receive in God in Christ.” He is preaching on the book of Ruth. Ruth! I studied it so many times in college, together with girlfriends all waiting for men, for boyfriends, for husbands, trying to glean some insight from this woman who did strange things indeed to secure her man. That is not the point of the book, the preacher says. I breathe a sigh of relief. Instead, he gleans kindness, hope, hospitality from the passages. The kind of hospitality that hems in, honors, and protects everything about the person being welcomed into our lives. “How can we offer the sheltering kindness of God to our neighbors?” the pastor asks. We fling open our doors to all of it: the sorrows and the needs and the depths of personality of the people we’re setting about to love. “Oh,” I say, rubbing my sore fingers. We learn the people who come through our door. We love them, whoever they are. We sit with them in joy and in sorrow. We listen. We bear their joys and sorrows along with them. I start pushing the needle through the fabric again.

This particular project is a cross stitch pattern. I have loved to do cross stitch since elementary school. So exact, the tiny linen squares, the counting. I have never much enjoyed the end product, too country for my taste. But sometimes, I need a good counted cross-stitch to apply my thought toward, and this one is a small purple bird with a blue snowflake wing. My oldest daughter watches the needle squeak in and out (she has always liked to watch me stitch), and says, “Oh! It is so pretty!”

I ask, “Would you like to have this in your room when I finish?”

“Oh, yes!” she says. I work harder at it.

The quilt top my Blacksburg friend pieced for me sits folded with its blues and greens on the corner of my writing desk, and it smells to me like the mountain air blowing up the hill in front of her house, and I can’t shake a craving for the BLT sandwiches she always makes when I come over, always on sourdough bread with egg and basil and guacamole, and also the conversations we have, when I talk and she listens and understands, or is understanding. Until my friend Amanda gets the chance to come back to my house, the quilt waits. It waits to be finished and I wait, and while we wait, I work, and when I don’t work at crafting words, I work at caring for my daughters in our house here, and sometimes I make things for them, and at the necessary times I feed them, and sometimes I play with them, and sometimes I watch them play with each other (and steal a few moments for stitching things), and sometimes friends come through our door, and I feed and listen to them too, and my youngest girl climbs on them and my oldest brings them books or something else special to show, like a glittering purple rock or the bird I cross-stitched. And in our work, our hearts are open, all the windows and doors of them — at least, I pray that in holding my own heart this way, my girls will learn to do the same, will learn the beauty of laying down that part of themselves that would prefer to stay shut safe and tight sometimes.

Amanda lays out house after pieced, stitched house on my kitchen counter and points out details of her fabric choices. “This one was done at night; the pattern looks like stars. And these were in daytime. The flowers.” She holds them between her thumb and forefinger and rubs them. She made them, and they are beautiful to her. The ones with the open doors are the loveliest to me. “You know what I will call this quilt when I hang it on my wall?” she asks. “Love Lives Here.”

Several weeks or months later, my husband comes upstairs after putting my daughter to bed. “You know what she told me tonight?” he asks. I wonder. “I love looking at the bird Mommy made for me.”

Photograph by Rebecca D. Martin

Photograph by Rebecca D. Martin

Rebecca D. Martin's essays have been published in The Curator, Proximity Magazine, and Coffee + Crumbs, among others, and she is a contributing writer at Makes You Mom. She lives in Lynchburg, Virginia, with her husband and two young daughters, and had the best conversation with her five-year-old the other day about bodies, souls, and bones at Lynchburg's Old-Cemetery-turned-botanical-gardens. You can find her online at Down the Rabbit Hole.