It's tempting for me to think about L'Abri as utopia. I now sit in a house filled with the chaos of unpacking and I look back on my family's two-month stay there this summer, the capstone on a seven-month European adventure. Any morning in June, our then nine-month-old son, Everett, would wake around 5:30, and the hours between then and breakfast tended to be lonely. In the spirit of the place, I tried to take advantage of the quiet time and the fact that we had the grounds to ourselves. On those mornings, Everett would be snug against my chest in his carrier, wool cap on his head, and we wandered the dew-covered yard tucked within an apple orchard. We visited the goats who came running up to the fence hoping for food, and we picked red currants to blend into Everett's breakfast. We tried to avoid the rooster, lest he charge at us to protect his baby chicks. We might stroll the rows of the orchard, and I would point out to Everett that the young apples had grown since the week before. And we wandered down the driveway, looking out for the moor hen family in the canal. In northern Europe, the sun would already be well on its way into the sky (not having gone down completely until around 1:00 am), and its reflection on the morning dew made the endless flat horizon of the Dutch countryside shine.

Despite the beauty around me, I still looked forward to breakfast, not just because my stomach was rumbling, but because the day would actually begin with the breaking of bread among friends. At 8:30 the other students would gather in the dining room; my husband, Eric, would join us, having already spent a couple of hours writing; and we would all sit down to the simple array of bread and various spreads — chocolate-hazelnut paste (i.e., Nutella), jams and jellies made from the fruit on the grounds, peanut butter, appelstroop (a thick syrup made from apples), and hagelslaag (chocolate sprinkles for breakfast!). We looked at each other bleary-eyed. The English might joke about the weak Dutch tea while the Americans whined over the absence of coffee.

I felt at ease gathered this way, around my family and friends as well as people I might have only just met. I never felt nervous when Everett spat out his food or let out a yelp; everyone laughed and made faces at him, and he loved the company and attention. All of our meals were together, as well as breaks for coffee at 11:00 and tea at 4:30. There might be as few as seven, or up to thirty other students on a particular day. Some stayed only a few days, but my family and I were part of a small group that stayed long-term. As the morning meal would conclude with a Scripture reading from a tutor, I took comfort in knowing that no matter what we each went off to do in the time between breakfast and the next meal, we would come back together, learn something from and about one another, and share in the blessings of our daily bread.

I realize that I am not alone among L'Abri students past, present, and future, in thinking of the place so idealistically. Life there is divided into time for study; time for simple tasks to maintain the grounds and prepare meals; time to enjoy those meals together; and time for lectures, meetings with a personal tutor, and discussion. Certain responsibilities, such as planning meals and doing laundry, are left to the staff. This structure provides a framework in which one can commit to a specific endeavor for a certain amount of time and be satisfied and appropriately tired at the end of the day. The logic behind this structure is not new but, rather, reminiscent of the monastic tradition: sharing the responsibility for necessary practical tasks actually frees up bits of one's head and heart for contemplation, prayer, spiritual wrestling matches, and nurturing relationships with others.

As one half of the only married couple with a child besides the tutors' families, I found the structure both liberating and challenging every day. The communal situation demanded selflessness, and the organization of each day meant that Eric and I had to learn new ways to navigate sharing time and space. We took turns caring for Everett's ever-changing needs and curiosities. We found time to do the things we loved — Eric worked on a book and I managed to finish several knitting and sewing projects. Most thrilling, however, was that we suddenly found ourselves acting as partners in new ways. We complemented one another during discussions, and I was proud to listen to his wisdom on many subjects. We developed friendships with other students as individuals and as a couple, inviting others to our apartment in those pre-breakfast hours for a cup of coffee or walking to town for a pint at the pub. He and I would sit while Everett slept and talk about our separate study projects and about the discussions we had had with our tutors. We grew immensely as individuals and as a team — as Christians, parents, servants, and scholars.

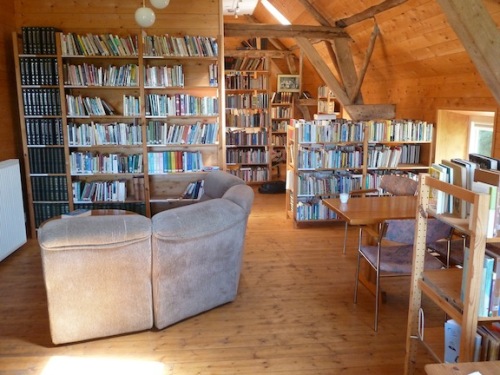

Photo: Noah Emrich

Photo: Noah Emrich

But growth cannot occur without a willingness to confront brokenness, and we found the extended stay crucial on this front. What felt like utopia for the first week or so began to break down as the reality of human nature came bubbling up in every interaction with this tight community. Even though Eric and I worked well together most of the time, having such a structured day sometimes resulted in a lack of time alone, which led to miscommunication and frustration. We both pursued new friendships with vigor, but Eric struggled with the scarcity of other men among the long-term guests, and I had to face a long list of deep-seeded insecurities as well as my tendency to judge by first impression. More than once I thought I had someone figured out only to hear a part of their story and discover I was abominably incorrect and needed to repent.

And you might imagine that as rich as having multiple perspectives around one discussion table can be, it was often equally frightening and painful. I have consistently struggled to live out emotional honesty and avoid breeding resentment, but living with others for this long meant that we all had to work through our brokenness together. We had to be honest or risk sitting in awkward silence over tea or the next meal, or, God forbid, be reduced to mere small talk while cleaning bathrooms together. Because of these interpersonal hurdles that could only be cleared with grace and mercy, I felt a quiet confidence growing in me, and my ability to listen and tend to the needs of others broke away from my need to have control or be independent. This, we found in the end, is the real bread and butter of communal life — forced honesty and a corporate desire to do more than merely share space and chores kept gossip at bay and challenged us to speak truth in love.

Eventually, the day came to leave. Eric departed a few days early to attend a conference in England, and when I met up with him in London after a flurry of packing, catching planes and trains, and calming Everett, I needed a moment to breathe. I felt like I'd been kicked out of the nest. I wanted so desperately to hold on to my newfound confidence about my ability to serve well, to remember the facts I'd learned, and for my son to continue to be surrounded by people from different cultures. I wanted to live in community and share chores (how would I go back to doing all of my own laundry?), and to share every meal plus coffee and tea breaks with my husband, dear friends, and my tutor. There have been days when it has been crippling to realize that this complex group of people, whom we had come to love and with whom we had shared such an intense experience of growth and learning, would not be coming to breakfast.

As we pulled into our neighborhood in St. Louis, the fear set in. I knew it wouldn't feel like home yet; I knew none of my stuff was where I left it; I knew I had to unpack, go grocery shopping, and wash clothes and sheets, and do it all with a baby who was nearly walking. I was not looking forward to any of it. We walked in the front door and dumped our bags. I began putzing around the kitchen while Eric went down to the basement to find something we'd stored there. He came back up the stairs and announced, "We have to leave."

Fleas.

The basement and backyard were infested due to stray cats our renters had cared for, so we couldn't move back in yet. We stayed in a hotel that night, but with the knowledge that resolution to the problem could take awhile, I called some friends from church who had a guest room and an extra crib. Everett and I stayed with them for several days while Eric worked on our house and yard and waited for the exterminator (it was the weekend). Tim and Liz were beyond generous — members of our prayer group but not friends we had spent a lot of personal time with. I was pleased to discover that we didn't slip into mere cordial conversation but enjoyed one another's company and shared parts of our stories bit by bit. They have two small boys, so our routines and needs matched up pretty well, and their demeanor was laid back and positive, despite having their own stresses. They welcomed us to stay for as long as we needed and never asked when we might be leaving. They fed us and even sent leftovers to Eric, who was fearful of bringing fleas into their house.

It was several days after we moved back to our own house before I realized that God was at work in the fleas. The delay in the realization was probably because I had in mind that He would call us to some great new form of service when we got home, having prepared us through our time at L'Abri. But there we were, displaced by the lowliest pest, with no choice but to rely on someone else for our shelter and daily bread. In a very tangible way, God showed me that communal living, a healthy dependence on others, and open honest conversations do not exist only at L'Abri. Returning home did not mean moving back into our little brick-and-mortar house — it meant taking up residence in a community. God has shown us our needs and is now showing us how we are needed here and how to love those around us. I feel called to know my neighbors better — many of whom are refugees from around the world — and to find new ways to serve our church.

I will always treasure our time at L'Abri and look forward to a time when we may return, but for now I am grateful for what it taught me about how to live among people who also have chores to do, who also have questions to ask, and who need to break daily bread with one another.

For more information on L'Abri, its 11 different locations worldwide, and how to stay there yourself or listen to some lectures by the workers at home, visit www.labri.org. It is worth noting that Dutch L'Abri, in Eck-en-Weil, The Netherlands, is the only campus that has a full apartment for families with children.

Emily Bryan is a wife, mother, maker, and reluctant home economist living in St. Louis, Missouri. She has a background in art history and museum education and serves as the coordinator for the Kingsbury Gallery at Grace and Peace Fellowship. She and her husband and son spent the better part of this year living in London, Shropshire, and Oxford, England; Reykjavik, Iceland; and Dutch L'Abri in Eck-en-Weil, the Netherlands. She enjoys a shameful amount of clever television, will bake you a cake if she knows you're coming over, and sporadically writes about all of this and more at http://alltherestofit.wordpress.com.