Photo: Betty McCracken

Photo: Betty McCracken

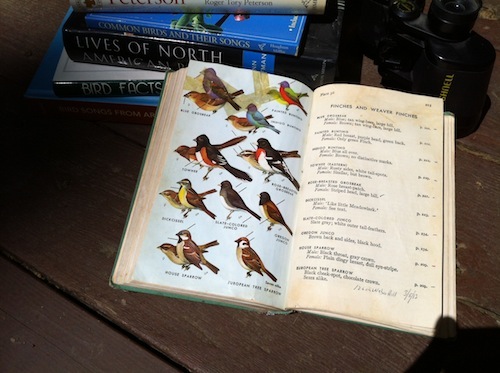

My father is a brilliant biology teacher, now retired. My mother is a thoughtful student of the Bible. They will have been married for 50 years this August. They have made records of their years of bird-watching in a worn Peterson Field Guide, plotting their dates and sightings together in the margins. They took me on nature walks as a child and we talked about the names of Missouri birds and trees and flowers.

Maybe that’s one of the reasons that I love Maltbie Babcock's "This is My Father's World." I love the line “He shines in all that’s fair” because this poetry has given me license to make art about all aspects of life. I have been shaped by the same kind of experience that Babcock describes in being able to taste and hear and see the glory of God in the skies, the flowers, and the birds singing their melodies like hymns.

In recent months, I’ve been reading John Muir's memoir and writing poetry and melodies about what it means to posture myself in such a way that is more mindful of my place in the world. Water. Electricity. Oil. Pesticides. Organic foods. As Muir wrote, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” We are all pulled and affected by our place and by each other. Our little choices do have consequences. And there is so much to consider — just reading labels at the grocery store can be a precarious business.

The more I learn, the more I find that unfortunately America has not had a stellar reputation for stewardship throughout history — logging, strip mining, and crop dusting, just to name a few problems. Nor has this been a pressing concern for most of the American church, whom you might think would be at the front lines ready to care for God’s creation. All too often, the topic of conservation quickly becomes political and we run to the safety of our pat answers. There have been some confusing lines drawn by both parties that do not add up to a consistent theology. The only way to get past these political blockades is to go up and over, elevating the conversation, speaking in nuances instead of sound bites, truly listening to each other, and looking for points of unity in spite of our differences. In fact, our diversity may be our best asset when it comes to seeking solutions for our environmental challenges.

One of the biggest hurdles for me personally in caring for the earth is that the problems feel so overwhelming. I cannot easily read National Geographic without feeling heavy-hearted about the realities of our condition, both within our own insatiably selfish hearts and in my sadness over the many species and habitats that we are losing along the way. And deeper still, if we are attentive to the words of Jesus and His care for the poor, the choices we make in the way of stewardship deeply cut into the survival of the people most desperate for these natural, sustaining resources. The poor are the first and hardest hit by these ecological losses and irregularities.

Photo: Sandra McCracken

Photo: Sandra McCracken

So with each passing day, I am becoming more attuned to the particular DNA I have from each of my parents — biology and theology — pushing me forward on the journey of conservation. I might be unqualified, but everybody has to start somewhere. Rather than burying my head in the sand like I am inclined to do, I have to lean into my discomfort. I’d rather deepen my longing, not assuage it. And I look to the great hope that all things will one day be restored and renewed. I want to honor and care for God’s creation not because of a marketing team pulling on my checkbook, but because of a doxological pull that tugs on my conscience.

As a songwriter by vocation, all of this comes out of me more as poetry than as politics. The wonder of the great outdoors creeps into the songs I write. My favorite time with my children is when we walk in the woods or explore the creek. We visited the Redwoods together in January and stood at the base of those 2,000-year-old trees in wonder. I can’t help myself from whistling back at the Towhee birds in Shelby Park. I am giddy when I hear or glimpse the Barred Owl that shares the beautiful old trees in our urban neighborhood. I wake the kids up some nights to see a particularly bright moon in the sky. And I will never get over the thrill of an airplane window seat view — seeing the horizon, the landscapes, the contours of the countryside, and the rivers carving spaces in between.

Recently, I had the great pleasure of hearing Peter and Miranda Harris, the founding members of A Rocha, a global conservation organization. They shared the story of their journey from a humble small group in Liverpool, to the Alvor estuary in Portugal, and now it has become an international network of conservationists in 16 countries. I had never before heard anybody speak with their particular blend of hope, ethics, and spirituality. It was a rare and powerful combination. As I sat in the room that evening, it confirmed in my own spirit that I'm on some sort of old-yet-new journey through these themes.

L to R: Jill Phillips, Sandra McCracken, Miranda and Peter Harris, and Jenna Henderson

L to R: Jill Phillips, Sandra McCracken, Miranda and Peter Harris, and Jenna Henderson

Miranda wisely confessed, “We cannot save the world — that’s God’s business. If we stop being in-process, we’ve lost the battle.” Knowing that we cannot control the outcome is really the beginning of the path, not the end. It is a small but real thing that each of us can enter into this practice of conservation believing that we can be part of tangible renewal. For some, it might take the shape of educating or gardening. For others it might look like banking or engineering, a public office or scientific research. It takes all kinds to accomplish the greater good. And it matters for us to practice renewal. It matters because God loves what He made, and when you love someone, you are drawn to love what they love.

At this invitation, we see that the earth is full of remarkable displays of God’s glory (Psalm 104). As we join together in earth-enjoyment, we come not just as individuals, but as a diverse family of people. This co-laboring to bring healing and wholeness is a simple call and yet a difficult one to abide.

This kind of unity is a challenge every day right under my own roof. In our family of four, from morning until night, we shift our weight back and forth to try our best to respond to the will and desires of each person. And therein is the conflict. My youngest child is three years old and she shows her will in full color. I, too, have a strong will, but a more grown-up version. The same goes for the other two. We each want things our own way. Sometimes we want to be left alone to have it our own way, but we need each other. We get frustrated. We want things to work but they don’t always work. And if Mick Jagger is right, that “you can’t always get what you want,” then could there be a higher objective for our desire?

The result of how we go about getting what we want extends out from individual families to neighborhoods, then cities, countries, and even out into the atmosphere surrounding our planet. Together we multiply our potential for sustainability, and together we multiply our potential for destruction. We react to each other with changing shades of conflict and complacency because we desire to have things our own way. Meanwhile, the honeybees in the clover fields, the fish in the ocean, and the polar bears on the ice caps go about their day-to-day lives. Their health and wholeness is directly and profoundly affected by how we work out our desires.

Jonathan Edwards, the great intellectual and theologian, made the case that we have free will, but that at any given moment we are slaves to our greatest desire. And our desires will function to guide our behavior whether we acknowledge them or not. James K.A. Smith, philosophy professor and author, puts it this way in his book Desiring the Kingdom: “Our love is aimed from the fulcrum of our desire — the habits that constitute our character, or core identity. And the way our love or desire gets aimed in specific directions is through practices that shape, mold, and direct our love.”

I confess that I am more than a little weary of my same old practices. I want to wake up and name my desires, to bring them out into the light. I want to see things as they are so that I can change and be changed. This is the beginning of care and conversation, whether it’s about protecting dolphins, or about the community garden, or about policy making on Capitol Hill.

No matter your life station, there is still some small good to be done. Maybe we can’t change the world, but we can do something. This summer, as we celebrate my parents’ 50 years of marriage, I realize that they have built 50 years of good things, pouring themselves into their family. They taught me to love the things that they love, shaping my desire for beauty and biology, and now I am able to spend some of that inheritance on my own little ones. No one may notice whether or not you recycle that cup when nobody is looking, or if you ride your bike to work, or if you teach your young nephew the difference between maple and oak trees. But a few small habits aligned for the greater good can add up to a whole garden of hope. And hope, like an eager seed, points us to a day coming when God’s green earth will be made new.

Sandra McCracken is an independent singer-songwriter whose smart, soulful blend of folk and gospel is as progressive as it is timeless. In the past 13 years, McCracken has released seven studio albums and two duo EPs with her husband Derek Webb; most recently, she has teamed up with a side band, Rain for Roots, to record and produce an album of children's songs. She is a founding contributor of the Indelible Grace hymn project, and her re-tuned hymns are sung in congregations across the country. McCracken currently lives, writes, and records at her home in East Nashville, Tennessee, with her husband, Derek Webb, and their two children.