It’s said that culture is a mirror held up to show us who we are. This can function in a number of ways, positive and negative. The shallowest culture acts as a funhouse mirror, distorting our flaws into a vision of sycophantic beauty, lying to our faces with its praises. As an aspiration and cautionary tale, reality television and tabloid culture often fall into this category.

But some of the best culture shows us ourselves far clearer than any real mirror, piercing skin to soul, and portraying us as monsters underneath. In the writing of Flannery O’Connor, we find such a mirror, and the experience of looking at ourselves through her eyes can be as entertaining as it is disconcerting.

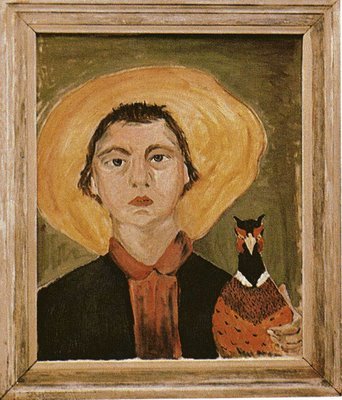

"Self-Portrait" by Flannery O'ConnorO’Connor grew up Southern and Catholic in Georgia, deep in the Bible Belt and yet, through her Papism, completely outside it. In 1951, at the age of twenty-seven, she was diagnosed with lupus, and would live only another thirteen years. In those short years, she helped develop the Southern voice in American writing as she acutely observed the culture that surrounded her. She left behind just one novel, Wise Blood, and several collections of short stories, but her impact is felt today in corners as diverse as the studious sci-fi of Lost and the silly Coen Brothers romp O Brother Where Art Thou?

"Self-Portrait" by Flannery O'ConnorO’Connor grew up Southern and Catholic in Georgia, deep in the Bible Belt and yet, through her Papism, completely outside it. In 1951, at the age of twenty-seven, she was diagnosed with lupus, and would live only another thirteen years. In those short years, she helped develop the Southern voice in American writing as she acutely observed the culture that surrounded her. She left behind just one novel, Wise Blood, and several collections of short stories, but her impact is felt today in corners as diverse as the studious sci-fi of Lost and the silly Coen Brothers romp O Brother Where Art Thou?

The word most often associated, positively and negatively, with her writing is “grotesque.” In our contemporary world, faced with the Saw movies at the multiplex and grisly war footage available for download, the physically grotesque is at our fingertips. O’Connor’s grotesques were often more spiritually deformed than they were physically morbid. A stolen prosthetic leg was nothing compared to the dark heart of a hustling Bible salesman.

It is here that she begins to draw out the tools with which she shows us ourselves. The Church then was as infested with sanctimonious sinners as it is now, and her writing offered no quarter. She turned the idealized pastoral on its head, showing that “Good Country People” were no better, and often a lot worse, than the city-fied folks they looked down on. But the prideful prudes were not the only targets of her pen; the seemingly well-meaning liberal intellectuals, with their haughty disdain for the Southern culture they’d obviously outgrown fare no better, often meeting ends just as gruesome or humiliating as the farmer’s wife gored by her own bull.

In the hands of another author, the blood and shame meted out in her stories would be cruel and nihilistic, a demonstration of an unfeeling universe smiting everyone alike. But O’Connor’s aim was different. She was focused at her core upon the Gospel, the arc of sin, redemption, and glorification, and though many of her stories stop short of redemption (much less glorification), redemption is the long shadow cast over the whole proceeding. At any moment, the hateful protagonist could reach out for mercy, destroy the pride within before it’s destroyed from without; the fact that the gracious offer is unaccepted only highlights the tragedy of not accepting it.

In the hands of another author, the blood and shame meted out in her stories would be cruel and nihilistic, a demonstration of an unfeeling universe smiting everyone alike. But O’Connor’s aim was different. She was focused at her core upon the Gospel, the arc of sin, redemption, and glorification, and though many of her stories stop short of redemption (much less glorification), redemption is the long shadow cast over the whole proceeding. At any moment, the hateful protagonist could reach out for mercy, destroy the pride within before it’s destroyed from without; the fact that the gracious offer is unaccepted only highlights the tragedy of not accepting it.

So the core of her writing is about this ache for redemption: the ache of the wronged character, beset by man and nature and longing for his tears to be wiped away; the ache of the reader who hopes for the best, knowing that the worst is on the very next page. It’s the sound of Creation’s very groans. As a character in “The Life You Save May Be Your Own” says, “Nothing is like it used to be, lady . . . The world is almost rotten.” It’s on the word “almost” that everything hangs.

On the few occasions that the redemption and glorification are found, they’re more like a ninth-inning home run: unexpected and triumphant. It’s the only closure that’s ever really found in her work, as everything else closes with a purposeful sense that retribution rather than redemption has been the order of the day. More often, the petty kingdoms ruled by the prideful characters come tumbling down on their own heads, ruined by hubris and the least of these whom they wronged.

The fact is, as I’m writing this, I’m desperately trying not to give the whole thing away. The stories are so vivid, so completely realized, that they’re breathtaking and impossible to put down. Though packed with imagery and portent, they are also supremely entertaining, and are like a candy shop for those who love literary detail. It would be a damned shame to give away any more than that.

Flannery O’Connor also stands as a challenge to Christian artists. She was surely one of the masters of her form, and received the accolades from the literary world that her talents deserved. She was in the world, to the degree that she could see its warts and pimples up close, and in the sense that she had the ear of taste-makers in academia and the publishing world. But she was not of this world, vigorously defending her Catholicism, her brutal, almost karmic, view of divine judgment, and the necessity of redemptive work that most decidedly does not come from within.

We live in the same fallen world that Flannery did, and we see the brokenness around us. Too often, we see the solution as the election of our favorite political party, the ascendance of our ideal solution, or the elevation of the national discourse. What we learn from O’Connor is that the desire to see evil change into good is as old and primal as the earth itself, and as futile as it is old. The ache, the despair that comes from this realization, is the common ground that she builds on. Flannery shows us that the Gospel story, the invitation to redemption and human flourishing, and not our own visions of grandeur, is the only elixir for these groans.

As she so often maintained, the grotesque in her writing serves to reveal the simple ugliness that exists in all of us. Her country bumpkins, children pining openly for their inheritance from still-breathing parents, tramps and laborers alike, meet their own reflection, and in their reflection we see our own. We might not like to swallow the truth that we are indeed looking at ourselves, but on a deeper level, we’re relieved to find that our own sin is not as cartoonish as it could be.

As she so often maintained, the grotesque in her writing serves to reveal the simple ugliness that exists in all of us. Her country bumpkins, children pining openly for their inheritance from still-breathing parents, tramps and laborers alike, meet their own reflection, and in their reflection we see our own. We might not like to swallow the truth that we are indeed looking at ourselves, but on a deeper level, we’re relieved to find that our own sin is not as cartoonish as it could be.

Though unspecific in both time and place, O’Connor’s stories clearly take place in her contemporary world, the Deep South still haunted by Reconstruction and uncomfortably lurching into the Civil Rights era. Yet the stories still ring true today; regardless of political persuasion, her control of her characters is so complete that you find yourself rooting against your will for the comeuppance of the character who most resembles you.

Rob Hays is a freelance writer from Houston. His work has appeared in Comment, Houstonist, The Curator, CultureMap, the Houston Chronicle, and an array of blogs for desperate fans of the Astros. His wife is significantly more well-rounded than he is. He's been known to wear bow ties, but it's not his "thing."