QU4RTETS — a collaborative project by painters Makoto Fujimura and Bruce Herman, composer Christopher Theofanidis, and theologian Jeremy Begbie — opened at Baylor University’s Martin Museum in December 2012 and Duke University in January 2013. This inaugural project of the Fujimura Institute will continue its exhibition and concert tour at Yale University later this month, Gordon College in April, and, hopefully, abroad this fall. Plan to attend if the show will land near you.

Graphic artist and singer-songwriter Sarah Duet and writer/editor Jennifer Strange took a January road trip to see the paintings in the Martin Museum, and this is their collaborative response.

I: On Reading and Seeing

So many writers and artists say they return often to T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets and that when they do, the poems make them want to make. Makoto Fujimura’s word for this is generative. Much in the Four Quartets emerges from specific cultural expressions of personal or community identity that quickly reveal broader truths moving beyond mere self-expression; the poems convey this energy and responsibility for culture-making to their readers, fostering in them the desire to do more culture-making. Thus, they are generative.

One way Eliot accomplishes this is by creating moments of selah throughout his quartets, just like Beethoven did before him, and just like every artist or writer inspired by Eliot has done. The poems act generously upon their readers, engendering in them the deep knowledge that they will only begin (to be, make, do, or live) when they rest and come to the end of themselves. Makoto Fujimura’s and Bruce Herman’s QU4RTETS do the same.

For this reason, we saw the generative power of Eliot’s Four Quartets anew as we visited QU4RTETS, because the paintings do their own good work in resonance with the poems that inspired them. We wanted to respond by making, not just critiquing or even experiencing. In fact, we spent our four-hour drive home that evening discussing work and beginning to outline several collaborative projects. We were intellectually and emotionally exhausted, yet enlivened for work (our various cups of coffee throughout the day helped, too). These paintings cause the viewer to take a life-giving, culture-making posture before she even realizes that she has begun to stand. This is the generative nature of good art/work.

II: On Stillness

Detail from Makoto Fujimura’s "Desire Itself is the Movement" (photo and type design by Sarah Duet)

Detail from Makoto Fujimura’s "Desire Itself is the Movement" (photo and type design by Sarah Duet)

In Four Quartets, we feel the tension of living in time, and this is part of the enduring legacy of those poems: Eliot reveals time as the vehicle of God’s saving work, for in time we simultaneously experience decay and life. In “East Coker” specifically, searching for the beginning of his real self leads the speaker of Eliot’s poem to determine that we truly become ourselves when we come to the end of ourselves. When we quit grasping for ourselves and instead get still.

Jesus put it this way: lose your life for his sake and you actually save it (Luke 9:24). “East Coker” depicts it again and again through paradoxes: possession through dispossession, health through disease, self-awareness through self-denial, individual identity through submission to a community of persons, true life through death to self. So Eliot’s speaker gets as still as possible in the universe. He will wait where there is no waiting, hope where there is no hoping, and thus settle into truth that he cannot totally comprehend but in which he can rest.

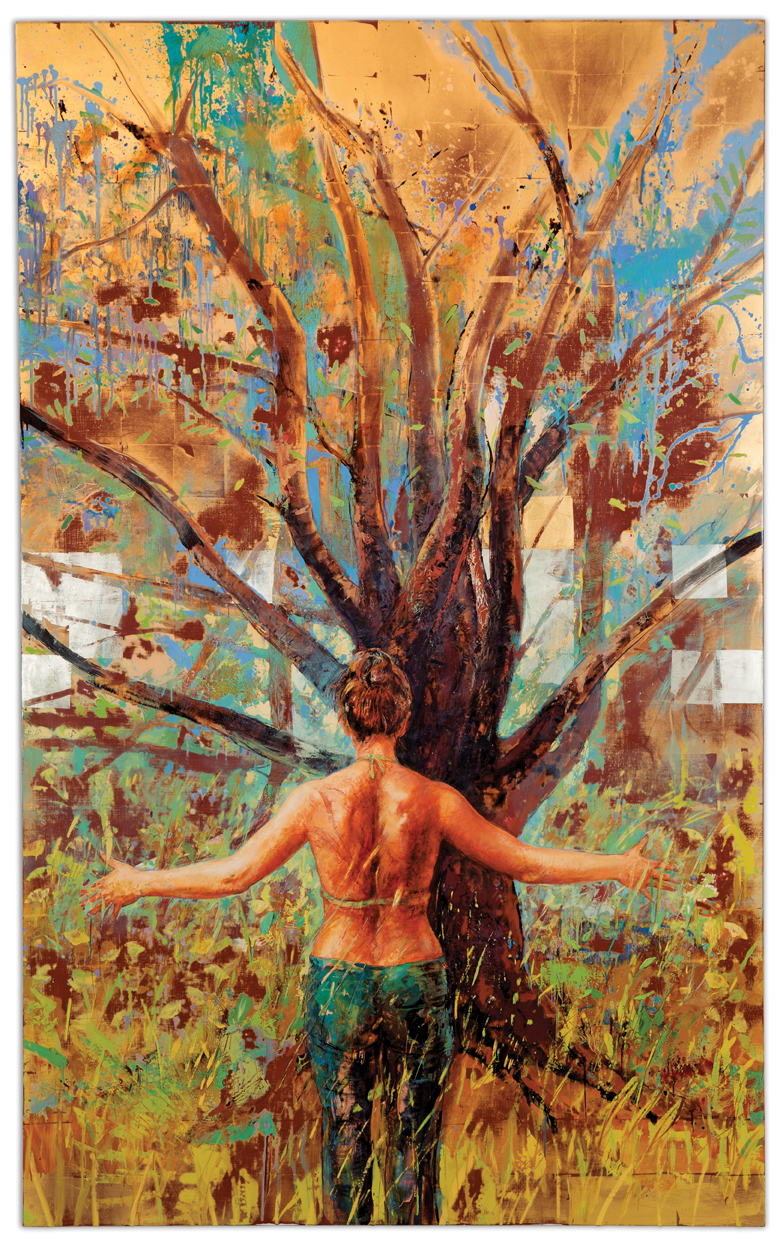

"QU4RTETS No. 2 (Summer)" by Bruce HermanQU4RTETS invites long, immersive contemplation as well. The exhibit space in the Martin Museum was one side room, which seemed shockingly small until we realized how essential the cozy room was to the stillness we eventually settled into in front of each piece. These paintings call for a kind of centeredness and focus that left us attentive to little else. We walked the perimeter of the exhibit, left for a coffee break, and returned to sit on the center bench for another hour, stepping forward to the paintings again and again.

"QU4RTETS No. 2 (Summer)" by Bruce HermanQU4RTETS invites long, immersive contemplation as well. The exhibit space in the Martin Museum was one side room, which seemed shockingly small until we realized how essential the cozy room was to the stillness we eventually settled into in front of each piece. These paintings call for a kind of centeredness and focus that left us attentive to little else. We walked the perimeter of the exhibit, left for a coffee break, and returned to sit on the center bench for another hour, stepping forward to the paintings again and again.

The woman in Herman’s QU4RTETS No. 2 (Summer) has her back to us, her arms opened wide to her tree, and her body seems to lift off its canvas. The figure in his Winter, who is Makoto Fujimura’s father, has fixed his eyes upon us; we watch him, stoop or bow a little, wait for his walk into the next age. His white, almost ghostly outline folds him into his tree, whereas the subtle red line underneath Summer’s arms gives her her lift; each figure in Herman’s paintings emerges from or recedes into the tree according to his or her age. But even as Winter folds into his tree, we draw closer to look directly at him rather than move back to take in the whole, as the vibrancy of Summer makes us do.

Detail from Bruce Herman's "QU4RTETS No. 3 (Autumn)" (photo and type design by Sarah Duet)Fujimura’s paintings, as always, employ abstraction to make the beauty and meaning we behold in his work. In QU4RTETS, he has crafted truly minimalist abstraction: even in QU4RTETS III with its gold-leaf grid, the painting offers stark contrast but little activity. Fujimura has said that he crafted his paintings intentionally for pause: “They are phenomenological. They require our senses to be quiet and still. . . . They require us to simply gaze and behold the painting for a while until your eye gets used to looking at it and open to the possibility of seeing something.”1 So do Herman’s paintings, and all — it seems — because Eliot’s poems do the same. It is in the stillness before each piece that one finally sees the glory of the whole.

Detail from Bruce Herman's "QU4RTETS No. 3 (Autumn)" (photo and type design by Sarah Duet)Fujimura’s paintings, as always, employ abstraction to make the beauty and meaning we behold in his work. In QU4RTETS, he has crafted truly minimalist abstraction: even in QU4RTETS III with its gold-leaf grid, the painting offers stark contrast but little activity. Fujimura has said that he crafted his paintings intentionally for pause: “They are phenomenological. They require our senses to be quiet and still. . . . They require us to simply gaze and behold the painting for a while until your eye gets used to looking at it and open to the possibility of seeing something.”1 So do Herman’s paintings, and all — it seems — because Eliot’s poems do the same. It is in the stillness before each piece that one finally sees the glory of the whole.

The individual movements within Four Quartets suggest certain themes and arguments, but only when read as a whole can they tell you the weight of those suggestions; the poems want quiet listening, like a Beethoven quartet where the silences of the rests and the space between the movements are every bit a part of the compositional whole as the melodic lines and discordant developments. We see this most pointedly in QU4RTETS in the two sets of four ancillary paintings — one by each painter — which offer meditations on specific lines in the Eliot poems and reflections with the larger works. The painters hint here at their major themes: water, movement, time, unity, paradox. The types appear easily without any essay telling you to watch for them, though the paintings are not didactic — they “are not here to verify, / Instruct yourself, or inform curiosity / Or carry report. . . . [but] to kneel / Where prayer has been valid” (“Little Gidding,” I.43–46).

III: On Glory

Lighting in the museum space will make every viewing of these paintings unique. In Baylor’s Martin Museum, the relatively dark room with spotlights on each canvas revealed something new at every angle. Walk toward a painting, and you will see the texture change: Herman’s figures begin to pop out from their gilding,2 and the deep gray or black background of Fujimura’s canvases seem to cave inward.

Both painters made use of a grid laid down in gold or silver leaf, but what is built on the grid differs. Herman uses an effective combination of figurativism and abstraction to express the progression of time — both in the four seasons of nature and in the aging process of human life, featuring one personage per painting. Herman’s use of color, detailed layering, and the reflective nature of the metallic grids create a kind of paradox for the viewer: they draw you in just as quickly as they send you backward, offering a rather different image from every angle because of the painting’s interplay with its lighting. Part of his craft is even paradox, for it seems that after his extensive and meticulous layering process, he sands through the layers of paint in some places to reveal subtle, polished white spaces, which remind us of the glimpses of pure glory that we can still find in creation.

"QU4RTETS III" by Makoto Fujimura

"QU4RTETS III" by Makoto Fujimura

The generosity of gold on Fujimura’s QU4RTETS III will blind the eye at a certain angle, suddenly refracting all of the spotlight’s intensity, and the blue and green hues on all of his canvases will only show themselves over time. Indeed, “the darkness shall be the light, and the stillness the dancing” (“East Coker,” III.128). Upon first glance, there’s no denying the excellence of QU4RTETS III, but we could only guess why after prolonged study, realizing that much as we tried, we could not divert our gaze from its corner of the room. We recalled, then, how C.S. Lewis spoke to the compelling nature of such beauty, saying that an encounter with something truly beautiful moves us to want more than “merely to see beauty . . . something else which can hardly be put into words — to be united with the beauty we see, to pass into it, to receive it unto ourselves, to bathe in it, to become part of it.”3 So Fujimura has given us a truly beautiful painting no less than Fujimura, Herman, Theofanidis, and Begbie together have given us a beautiful gift in their collaborative project.

IV: On Gospel

Detail from Bruce Herman's "QU4RTETS No. 4 (Winter)" (photo and type design by Sarah Duet)QU4RTETS is incarnational and generative in the same way that Eliot’s Four Quartets is. Eliot accomplishes his work through fragment and paradox, offering a unified contemplation of the human project through four poems in five movements each. Gregory Wolfe, in his foreword to the exhibit catalogue,4 says Eliot’s poetic language accomplishes its brand of wholeness through its fragmentation: “paradox simultaneously respects reason and points us toward mystery, a place that reason alone cannot reach.” So too, Fujimura and Herman offer a unified contemplation of the ironic hopefulness of decay — hopeful because only the person or planet in decay can be redeemed. Their paintings operate as pieces of a unified whole, and in their whole expression we see the mystery of glory.

Detail from Bruce Herman's "QU4RTETS No. 4 (Winter)" (photo and type design by Sarah Duet)QU4RTETS is incarnational and generative in the same way that Eliot’s Four Quartets is. Eliot accomplishes his work through fragment and paradox, offering a unified contemplation of the human project through four poems in five movements each. Gregory Wolfe, in his foreword to the exhibit catalogue,4 says Eliot’s poetic language accomplishes its brand of wholeness through its fragmentation: “paradox simultaneously respects reason and points us toward mystery, a place that reason alone cannot reach.” So too, Fujimura and Herman offer a unified contemplation of the ironic hopefulness of decay — hopeful because only the person or planet in decay can be redeemed. Their paintings operate as pieces of a unified whole, and in their whole expression we see the mystery of glory.

Bruce Herman has put it this way: “Poetry and paintings are not merely a means of communicating ideas or messages. They are a form of making — making a new thing. A fundamental human act that says ‘yes’ to the mystery of things, our very physical existence.”5 So the Four Quartets, Herman says, give us “ourselves,”6 and so do QU4RTETS in their generative response. They give us reality packaged in a form of beauty that we can actually bear, and by which we can be enlivened to enter the world more fully — starting with the stuff of our everyday lives. These paintings, as the poems before them, express real hope — that which is neither sentimental nor despairing. It is the incarnational hope in which life begins in full after what seem to be the darkest, most difficult moments — the kind of moments that pose as the end of things.

We close our response, then, considering Eliot’s “East Coker” again, for it centers on an expression of an end-of-things paradox that profoundly articulates the Christian gospel: “In my end is my beginning.” This is the generative point for Eliot’s poems, and for all who have followed them, like Fujimura’s and Herman’s QU4RTETS. They show us that death of self begets real life. And real life is found where life begets life — where it is generative. So Fujimura’s and Herman’s paintings share in this generative nature because they emerge from and also express that same end-beginning point. And so we honor their works best when we too join in making. When we come to the end of ourselves at the still point of the turning world and — then, there — begin.

Detail from Makoto Fujimura’s "The Voice in the Waterfall" (photo and type design by Sarah Duet)

Detail from Makoto Fujimura’s "The Voice in the Waterfall" (photo and type design by Sarah Duet)

1 “Engaging Eliot: Four Quartets in Word, Color, and Sound,” Duke University, January 28, 2013.

2 See the video about this process embedded in Charlie Peacock’s Art House America Blog interview with Bruce Herman.

3 C.S. Lewis, “The Weight of Glory,” The Weight of Glory and Other Addresses (New York: HarperCollins, 1949/2001), 42.

4 QU4RTETS (New York: Fujimura Institute, 2012) can be purchased from the IAM store online.

5 “Engaging Eliot: Four Quartets in Word, Color, and Sound,” Duke University, January 28, 2013.

6 Ibid.

Sarah Duet is a freelance graphic artist, sometimes singer-songwriter, and coffee-obsessed barista based in Shreveport, LA. She is also a founding member of the Yellow House, an intentional community for young adults, and an intern for the Art House America Blog. You can find and follow Sarah’s work at www.duetartanddesign.com.

Jennifer Strange is the assistant editor of the Art House America Blog. Also a wife, mother, writer, editor, Twitterer, annual reader of Four Quartets. She contributes regularly to this blog, and her poems have appeared recently in The Other Journal and The Southern Poetry Anthology, Volume IV: Louisiana published by Texas Review Press.