Growing Up With Imogene Herdman

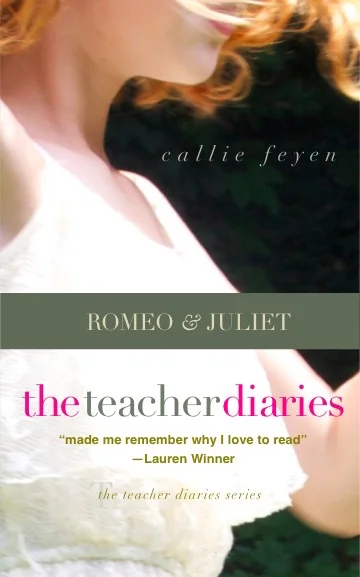

Photograph by Callie Feyen

There once was a family I’ll call the O’Hannigans. (They were Irish, and there were a lot of them.) They wreaked havoc in the neighborhood. They would push you off your bike, or wait for you in the locker room of the community pool so they could steal your quarter and you couldn’t get a Fireball or Superope during the rest period. One summer, the O’Hannigan kids stuck a firecracker up a hornets nest, and one little girl whose name I have forgotten but could play the piano like Mozart got stung on the inner part of her thigh and screamed so loud we could all hear her over the Chicago el. None of us were allowed outside for weeks that summer.

I was particularly afraid of Stacy O’Hannigan. She wasn’t much older than I was—two years at the most, but she was bigger, and because I was quiet, and, I’ll be honest, cried a lot, I was on her radar. Stacy never laid a hand on me, but she liked to harass. She’d sit on the front steps of her house, and if she saw me coming, she’d yell how much she hated me, how much she wanted to hit or kick me. She made fun of my snow boots, my haircut that for years was in the perfect shape of a bowl; anything was fair game. I was terrified of her.

The O’Hannigans lived across the street and about seven houses down from me, and every morning, as I wrapped my feet in plastic bags and then shoved them into my boots, I worried that Stacy would come out of her house at the same time I came out of mine.

That never happened, and as a matter of fact, I cannot remember ever seeing Stacy walk to school. I remember her brothers, tall and gangly. They took long strides and almost bounced when they walked; their heels never touched the ground. I know this because I used to try and walk the same way. The way they walked looked fun.

I can’t describe how Stacy walked. I only paid attention to whether or not she was around, and when she was around, I was afraid. My fear was all I chose to feel and see.

This was right around the time I met Imogene Herdman from The Best Christmas Pageant Ever.

My family read two books around Christmas time: Madeleine L’Engle’s The Twenty-Four Days Before Christmas, and Barbara Robinson’s The Best Christmas Pageant Ever. I don’t remember a word of L’Engle’s book, but I can recall all sorts of information about the Herdmans: How Imogene ratted out kids who had lice or any other deep, dark embarrassment. How they set fire to things and stole treasures from other kids. How they lived over a garage and for fun, “used to bang the door up and down just as fast as they could to try and squash one another.”

Indeed, I knew all about the Herdmans; I lived across the street from a real live set of them, and as we read The Best Christmas Pageant Ever, fear started to fade and intrigue began to grow. This was the first time I rooted for the alleged bad guy.

I laughed slyly when my parents read the scene where the Herdmans stole money out of the offering plate at church, and I nodded in agreement when they insisted that King Herod needed a good beating. I eagerly awaited for what the Herdmans would do next. Would one of them say something sassy to an adult? Would there be a fight? Perhaps a practical joke would be played. I was more than anticipating trouble; I was looking forward to it. I admired the Herdmans, particularly Imogene.

I loved that she wanted to be Mary in the Christmas Pageant, but what’s more, I loved how she went about getting the part—telling Alice, the know-it-all tattle tale and goodie two shoes who always plays Mary that she will “stick a pussy willow so far down your ear that nobody can reach it” if Alice doesn’t let her have the part. Sure, Imogene did something bad — we shouldn’t threaten other children to get what we want, of course — but Alice was so annoying and she always got to play Mary. There was something creative and relieving and perhaps heroic about Imogene snatching that part from Alice.

I loved when Imogene heard the Christmas story for the first time, and she kept interrupting with questions and opinions.

“No room in the inn? Not even for Jesus?”

“You mean they tied him up and put him in a feed box? Where was the Child Welfare?”

“My God! He just got born and already they’re out to kill him?”

I think I lived out a bit of a fantasy through Imogene. I was always afraid of the Christmas story, especially when I turned 12 or 13, the age Mary was when Gabriel paid her a visit and totally changed her world. Even though Imogene might not have been satisfied with the answers, she wasn’t afraid to ask her questions. She showed me how to wrestle with a story.

I loved that Imogene wore big hoop earrings to the dress rehearsal and wanted to be the one to name the baby. On the night of the Pageant, I loved that she burped the baby doll she was carrying before placing him in the manger. I loved that Imogene cried during “Silent Night.” I cannot think of a Christmas Eve service when I didn’t cry during this carol, and knowing Imogene cried too—knowing she didn’t understand all of this story but demanded to be a part of it—made me feel good. I was happy to have something in common with Imogene. I wonder if that’s what a good character in a book does: imprints herself on you so that when the story ends you’ve layered a bit of her onto you, and she fits, and where she ends and you begin is intertwined forever.

I never got over my fear of Stacy O’Hannigan. I would always be on the lookout for her, even when I was married and a mother coming back to visit my childhood home. Once, though, and only once, I was with Stacy and I saw more than my fear. We were in high school, and we were both waiting outside of the Dean’s Office. I was there because instead of taking my study hall and lunch periods to write a report on the geological findings in the Shenandoah Valley, I convinced my best friend Celena to drive with me to the city and maybe do a little shopping at Water Tower. I don’t know why Stacy was there, but I don’t think it was to get signatures for Student Council.

When Stacy saw me, she accidentally on purpose hit me in the side with her elbow when she sat down, which brought tears to my eyes. I didn’t want to cry in front of her, so I began to pick at my nail polish to distract myself.

Our dean—a big, loud man—opened his door, and I jumped at the click the handle of his door made.

“You two?” he bellowed. “What are you doing out here?”

“No, no,” I began.

“We’re not together,” Stacy said, shaking her head vigorously.

“I don’t care,” he said. “You’re coming in my office together. I don’t have time to deal with you individually.” He turned and walked back into his office, and the door slammed behind him.

Stacy sort of snorted, shrugged, and stood up. I followed her in, afraid of my punishment, but slightly relieved I wouldn’t have to face the dean alone. I’d be with Stacy.