Though dark clouds have certainly passed and lingered before my eyes during this particularly slow period of work, I have not yet resorted to loitering on the couch, consuming Twinkies, and watching Ricki Lake reruns. On the contrary, I have striven to keep myself occupied with various odds-and-ends work while delving into new, creative ventures I never would have imagined myself participating in even just one year ago. In truth, this may have been the most creatively fruitful season I have experienced in my entire life — unquestionably so since first becoming a parent five years ago. For this reawakening and exploratory migration, I have, in part, John James Audubon to thank. For the courage and willingness to utterly fail, I have Christ the Lord.

In reading Richard Rhodes’s tremendous 2004 biography of Audubon, I learned how much (and how little) I have in common with the man, husband, naturalist, and artist: he deeply admired birds, desperately needed light, professionally failed as a businessman, enjoyed the support of an incredible wife, and worked with an insatiable desire to create, to see color, to offer beauty, to make art — ideally, of lasting and permanent value.

In 1819, after his Henderson, Kentucky, business failed miserably amid a national economic disaster, Audubon and his family were reduced to few material possessions, significant financial debt as Audubon himself suffered a dark psychological depression, a melancholia with which I can all too easily sympathize. However, rather than succumb to the despondency of the circumstance — the “saddest of all my journeys,” he wrote — it was at that crucial and pivotal moment that Audubon, broken but not hopeless, wholeheartedly devoted himself to what had heretofore been mere hobbies of collecting, drawing, and painting bird species. With a stout heart, he dreamed of self-publishing an immense work, an opus of his own heart, mind, and hands which, if successful, would allow him to solely — perhaps even comfortably — support his wife and two sons. It was the unbridled American spirit, newfound in Audubon.

This monumental and risky undertaking, The Birds of America, would consume the next fourteen years of Audubon’s adult life, nearly to his own detriment. To support and fund it, Audubon traveled throughout America, France, and the UK to solicit subscribers and patrons (ahem, Kickstarter, circa 1825), collecting specimens, painting, exhibiting, and selling subscriptions to the voluminous work with inexhaustible vigor and determination. At nearly every stop, he painted commissioned portraits, mailing this much-needed income to his ever-faithful and equally stout-hearted wife, Lucy. In short, Audubon leaned into his talents even though it was risky, trusting himself to them and giving himself fully to his innate need to create.

“The world was with me as a blank, and my heart was sorely heavy; and yet through these dark days I was being led to the development of the talents I loved.”

During my own particular downturn, in addition to the time spent working on and recording an album, I have invested my energies in creative pursuits: painting, reinvesting in an old passion for B&W 35mm and Holga medium format photography, and woodworking. Not to mention my peculiarly obsessive home landscaping — a venture that is without end.

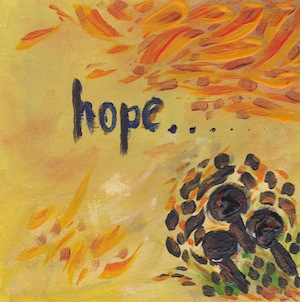

"Hope" by Eric Peters

"Hope" by Eric Peters

Temporarily set up in a corner of our master bedroom, with a library of books and two children clambering for my attention, I paint. Here in this domestic non-quiet I dream of securing a separate, private studio space, a dedicated work area where I can paint, write, and, if running water is available, establish a twentieth-century-era darkroom — a venue where my archaic Leitz enlarger, developing equipment, and my mind can together sow veritable seed, a place where scenes can appear from out of nowhere on the stark white space of imagination. I like to think this hope of mine is not wishful thinking.

With piles of wood siding and tongue-and-groove bead-board spared from our recent house addition, I, being too cheap (or wise) to relegate 100-year-old oak and pine planks to the wastes of a garbage dumpster, have begun repurposing much of it, building and constructing objects I never knew I could make: picture frames, a bunk bed, work table, key rack, coat hanger, various house décor. I have, in short, delved into the realm of folk art. More pragmatically, in addition to these more or less creative outlets, I work sundry odd jobs to make ends meet: mowing lawns, pruning trees and shrubs, cleaning gutters, painting houses, degreasing kitchen appliances, cleaning up construction sites, substitute teaching, hanging ceiling fans. The list goes on ad nauseum, and rarely do the so-called ends actually meet.

There is never a simple answer to the question I am frequently asked: “What do you do with your time when not touring or playing music?” Perhaps the better question is, Why do you do what you do? Why cull together (more like cobble) a mishmash income year-in and year-out — each year the same, each one different, each one in hindsight a miracle? The years carry with them the same struggle, the same burden, only clothed in different hides. Some years are grimier, more pungent than others.

That word: struggle. We bristle at it. The Greeks were no fools in their assessment: Mathe pathein. Learn to struggle. I ask again, Why bother? Why prolong a waffling, often floundering, capitalistically failed career? Why persevere? Why hope in distant dreams? Here, reader, you must believe me for I ask myself these very questions on a daily, if not hourly, basis. Too often the voices I lean into are ragged, mercilessly cruel, and tyrannical in their damning condemnation. And if they damn me, they surely damn God, in whose image I am made. And if it is true that we are never fully alone, then the voices, reader, surely curse you as well. Take heart in Audubon’s response during his tremulous days of depression immediately following bankruptcy:

“Hopes are shy birds flying at a great distance, seldom reached by the best of guns.”

Hopes are slight angles. Without them — the birds and the hope — we have no need for light, no need for a soul. Without them the world goes pale and silent. St. Matthew’s birds of the air flutter across the sky, and the flurry of their incessant song trills new beginnings. “A bird doesn’t sing because it has answers,” quoting author Sally Lloyd-Jones. “It sings because it has a song.” Carry forth, carry on; carry, and be carried.

“Look at the birds of the air; they do not sow or reap or store away in barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not much more valuable than they? Who of you by worrying can add a single hour to your life?” (Matthew 6:26-27)

Eric lives in a quiet historic neighborhood in east Nashville with his wife, Danielle, and their two boys. When he's not on the road playing his songs in front of human beings, he writes songs and, every couple of years, records them. Which is what he is doing now, recording his ninth studio album, Birds of Relocation. When he's not doing that he paints, changes diapers, tends to his burgeoning lawn care business, and ponders quirky things. Eric enjoys birds, manicuring lawns, and eating well-seasoned nachos. He has no love for snakes, but he does enjoy making music he himself would want to listen to, and painting images he himself would want to look at.