There’s something to this whole believing like a child thing, I sometimes think. One doesn’t have to think hard to remember all the scriptural admonitions to do so, starting with Jesus’ declaration that we must become like little children in order to enter the Kingdom of Heaven.

But what about the flip side? What if you’ve grown up in church believing strongly and simply in a certain set of ideas — in the image of God presented to you by those around you — and you find, as more and more candles are added to your birthday cake, that you are unable to believe in the same way or with the same certainty? As anyone who has struggled with this can tell you, these are not easy questions to try and sort through. Maybe that is one reason we find such comfort in the words of others who are processing the same things. That need to know we are not alone — that others are thinking through similar issues — is one reason I find so much to value in the work of Rob Mathes.

But what about the flip side? What if you’ve grown up in church believing strongly and simply in a certain set of ideas — in the image of God presented to you by those around you — and you find, as more and more candles are added to your birthday cake, that you are unable to believe in the same way or with the same certainty? As anyone who has struggled with this can tell you, these are not easy questions to try and sort through. Maybe that is one reason we find such comfort in the words of others who are processing the same things. That need to know we are not alone — that others are thinking through similar issues — is one reason I find so much to value in the work of Rob Mathes.

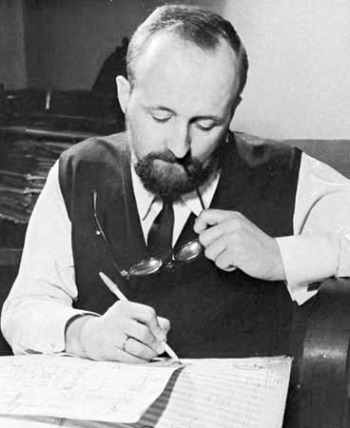

Rob is a busy man. He writes and records songs for his own albums, but only when he is not listening to the symphonies of Gustav Mahler (just one reason I like him: he’s a bigger Mahler nerd than I am), serving as the primary arranger and co-producer of Sting’s new album Symphonicities, writing hit songs for the likes of Kathy Mattea and Rascal Flatts, producing albums for Vanessa Williams and Panic at the Disco and Bettye LaVette (to name just a few), serving as the musical director for the annual Kennedy Center Honors and the star-studded “We Are One” Obama inauguration concert, and writing 25-minute orchestral works based on the poetry of Wendell Berry for the Nashville Symphony.

Rob’s 2002 release, Evening Train, is currently my favorite and most-listened-to album in my collection. Among the songs I listen to most on the album, one speaks to this idea of the struggle to believe. Rob builds ”When I Was a Child” around a conversation he had about faith with his grandfather who “used to drive the train from Providence to New Haven.” In the chorus, Rob sings:

When I was a child, when I was a child,

I spoke like a child, I acted like a child,

I thought like a child, but I believed like a child.

Now that I’m a man, I wonder

will I ever believe that strongly again?

From the first time I heard that song, I knew that it put into words something I had probably been afraid to ask. As I move farther and farther away from the way I believed as a child, is there anything left to hold onto? Is it possible to believe in anything so strongly again? In the song, Rob describes his grandfather’s faith and recounts a story his grandfather told him about “a train wreck in the ’60’s,” which brings up what theologians call theodicy, the problem of the existence of evil if there is a God. Rob responded to that story by asking his grandfather if “he ever thought the heavens were cold,” and the answer, Rob told me one rainy afternoon over coffee at a Starbucks in Cos Cob, Connecticut, is one he is unable to sing to this day without his voice cracking: “Son, to tell you the truth, I have loved my Creator since the days of my youth.”

For the first couple of years after I first heard “When I Was a Child,” as much as I loved it, there was one part I never understood — where Rob sings, after the second and third choruses, “I think I need a hymn,” followed by an eight-bar chorale melody, played the first time by a brass section joining the band, and the second time adding a choir and repeating it twice. It wasn’t until I listened to the 76-year-old Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki lead the Nashville Symphony in a couple performances of his piano concerto earlier this year that Rob’s song finally made sense to me as a complete idea.

For the first couple of years after I first heard “When I Was a Child,” as much as I loved it, there was one part I never understood — where Rob sings, after the second and third choruses, “I think I need a hymn,” followed by an eight-bar chorale melody, played the first time by a brass section joining the band, and the second time adding a choir and repeating it twice. It wasn’t until I listened to the 76-year-old Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki lead the Nashville Symphony in a couple performances of his piano concerto earlier this year that Rob’s song finally made sense to me as a complete idea.

Penderecki started writing his piano concerto in the spring of 2001, intending it to be a lighter work, but after the events of September 11th, he changed direction, building the concerto around a short chorale melody he wrote that same afternoon, and titling the work “Resurrection.” “The title,” Penderecki has said, “should be understood in a wider, symbolic, and universal context. It stems from the chorale that crowns the work and is a symbol of life’s victory over death, of faith bringing consolation.”

Throughout the work, amid the dissonance and often dense orchestration one would expect to hear in a 21st-century piano concerto in the tradition of Bartok and other modern classical composers, you hear bits and pieces of the chorale melody poking through — two bars played by the woodwinds here, four bars from tremolo strings there. It is not until the final section, that you hear the chorale melody stated in full, played by most of the orchestra, the chimes ringing out like church bells over the orchestra, the pianist playing arpeggios up and down the keyboard. I found myself unexpectedly blinking back tears when three trumpets joined in from the upper balcony, the melody soaring over our heads and swirling around in the far corners of the hall.

I returned the next night, dragging a friend with me, ready to sit through everything else on the program again just for those couple of seconds when the hairs on the back of my neck stood up. And I understood something a little better that night about our need for music, for a wordless hymn that communicates what we cannot put into words, something perhaps best described as “a groaning that cannot be uttered.” Something that gives voice to the mystery around us, reminding us that despite whatever objections we have, something exists beyond ourselves. This is also what Rob Mathes’ song “When I Was a Child” accomplishes: that mysterious confluence of certainty and uncertainty in the knowledge of the divine.

Will I ever believe as strongly as I did as a child? I don’t think so. But surrounding myself with great music will at the very least help me avoid a descent into nihilism and complete cynicism. Maybe that is enough for today. And next time I listen to Rob sing about his need for a hymn, I think I’ll turn up the volume and sing along.

Stephen Lamb lives in Nashville, Tennessee, where he works as an arranger, composer, and copyist. When he’s not printing out another thousand pages of music for a studio orchestra or a symphony orchestra somewhere, you can usually find him hanging out at a local coffee shop or pub, book or journal in hand; playing board games with friends; or smoking his pipe while sharing good conversation over a single malt scotch, a pint of Guinness, or pretty much any kind of coffee or tea. Sometimes he dreams about being a writer. He blogs at Rebelling Against Indifference and The Rabbit Room.