I remember the first time someone actually purchased one of my CDs. It was 1999 at a roller-skating rink in Sacramento, California, where I was opening for a ska band (a story unto itself). The kid who made the purchase had blue hair and was probably sixteen. He handed me sweaty cash from his pocket saying, “I didn’t think I’d like you,” which I took as a compliment. Further, I took it as a sign that I’d made a connection and, as corny as it may sound, I was actually moved. This kid was willing to part with his money in exchange for my music. He was, in a small way, “in this thing with me.” I had left an oh-so lucrative career as Young Life staff, earning upwards of $400/month, to take a risk on music. This kid was taking a risk on me.

I remember the first time someone actually purchased one of my CDs. It was 1999 at a roller-skating rink in Sacramento, California, where I was opening for a ska band (a story unto itself). The kid who made the purchase had blue hair and was probably sixteen. He handed me sweaty cash from his pocket saying, “I didn’t think I’d like you,” which I took as a compliment. Further, I took it as a sign that I’d made a connection and, as corny as it may sound, I was actually moved. This kid was willing to part with his money in exchange for my music. He was, in a small way, “in this thing with me.” I had left an oh-so lucrative career as Young Life staff, earning upwards of $400/month, to take a risk on music. This kid was taking a risk on me.

I also remember the first time I heard someone talk about “stealing” my music. It was 2001 at a theater in Athens, Georgia, where I was opening for Caedmon’s Call. One young man was about to purchase both albums I made available that night. His friend stopped him and said, “I found his stuff online. I’ll just rip it for you.” The young man handed the CDs back to the foxy dame (my wife) behind the table and said, “Thanks.”

I wouldn’t have been able to articulate it then, but the sting of that ‘01 moment was not the loss of a sale. It was the loss of the connection I first experienced in ’99. In its place was the sense that what I was making was just one more item like any other, the value of which was determined solely by the machinery of the marketplace. I understood I was a part of the machinery that routinely marked CDs up to $17.00 or $19.00 in stores (artists saw only a fraction of that) and those who had become wise to that broken system were rather unwilling to pay into it, even in support of an artist they valued.

Where that connection had been severed in the past by either the short-sighted greed of industry or the short-sighted selfishness of buyers, some mending has begun in recent history. The most visible sign has been the prevalence of free music options provided by artists. Be it a giveaway at an artist’s web site, the use of NoiseTrade, or even the added bonus material provided with purchase of an album, artists have been working to meet buyers and listeners closer to their side of the tracks. But at the same time, art consumers are taking similar, relational steps toward the arts, and I believe this is where the rubber meets the road.

The truth is, most artists will never be “hot” enough or long-term enough to make a career of it. That takes the consistent support of invested listeners. This has always been true at the root of things, but the collapse of old marketing machinery has exposed those roots recently, and the connection between the artist and the listener is much more vital.

A year ago, if we were talking about an artist asking his fan-base to help fund a project, we would either be talking about a local artist or something very new and unfamiliar. But in recent days, notable names like Over the Rhine, David Mead, and David Bazan have funded albums through crowd-funding. Similarly, Donald Miller used Kickstarter to raise an eventual $345,992 to fund a film adaptation of his book Blue Like Jazz. What this said was more than just “Donald Miller has a lot of fans.” It said that these fans feel sincerely connected to his work and that, given the opportunity, they would even take some level of ownership and responsibility for it.

It is this symbiosis that, I hope, defines the next chapter for the arts. But there is a catch.

In the same way that artists have had to change their approach to consumers in light of the brokenness of the old system, responsible and interested consumers must continue to change their relationship to art. Just as artists must continue down the road of greater access and relationship to their fan-bases, patrons of art might want to consider planning accordingly, particularly as they continue to share in the process by which art is produced and distributed.

“What are you saying, McRoberts?” you might ask. “Are you asking me for money?”

Well, not right now, and not for me, but I am suggesting this:

The list of artists who will be asking for help to make art is only going to grow in the coming days. Plan on actually “getting in this thing,” and be there when they ask. Like you might plan to give a percentage of your income to charities doing redemptive work in the world, consider doing the same for the arts. You see, we all took part in dismantling the old system, and we all have a part in building something new. It just so happens that in this rebuilding, the role that consumers, listeners, and fans play is far more central, far more vital, and way more fun.

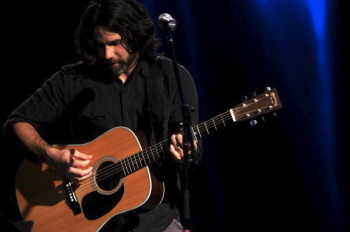

Justin McRoberts is a singer-songwriter and storyteller from the San Francisco Bay Area where he lives with his wife and their son, Asa. He thinks aloud at his blog: www.justinmcroberts.com/blog.