The red and yellow tomatoes contributed some of their juice to that of the lemon and olive oil to make a sauce, taking flavor from the fresh-chopped thyme. Strewn thickly across the pasta I’d just tossed with water, ricotta, and parmesan cheese, those tomatoes provided the loveliest sight I’d seen all day.

Not even nine hours straight spent staring at the e-mails and ever-imperfect edits that had marched across my computer screen at work could rob me of this latter-evening respite. Best of all, a handful of roasted pecan fragments spiked the dish with protein and crunch, accompanied by memories of the December afternoon when I roamed through my aunt’s front yard in Dallas, retrieving the fallen nuts buried in the latticed but hardy grass beneath her front yard trees.

Though I brought home close to five pounds of nuts, they’ve proved so time-consuming to shell — even with the special nutcracker I ordered for them — that I’ve strung the pecans out almost a year, saving each batch of carefully shelled meats for special cooking projects like a jar of cranberry conserve or the granola I stir into yogurt and homemade jam each morning. I did not regret using a few more for my pasta feast.

When co-workers learn what sort of breakfast I’ve brought to a mid-morning meeting or spy the leftovers just heated up for lunch, they sometimes marvel at this “talent” for using a spoon to stir grains together or my hands to chop onions by knife. Sometimes they even suggest I turn my cooking skills into a business.

To judge from our daily work together at the office, hands mostly serve to type, swipe security fobs, and touch screens, push buttons, or occasionally, move papers in and out of copy machines and printers. Mouths serve to answer phones, form responses in meetings, and gulp down the usually bad-tasting caffeinated drip we’re not yet able to mainline in the morning.

Noses cause inconvenience, mostly — especially when someone’s dared to reheat leftover fish or we’ve timed a bathroom visit poorly. Only on major employment anniversaries does the company give our noses a treat, but even then it may smell more like a florist shop than the individual blossoms assembled in the bouquet. (I’ll never understand why pre-cut flowers so rarely smell as bold and distinct as my childhood neighbor’s yellow roses, which tossed their scent at us over the backyard slats, as if they knew I liked to stage fake weddings with my siblings and the neighbor girls there.)

No, what my company really sought when it hired me — what I imagine most white-collar firms do — was a sharp brain attached to just enough functioning eyes, ears, hands, and lips to maximize their returns on my neurons. Our bodies matter mainly during weekends.

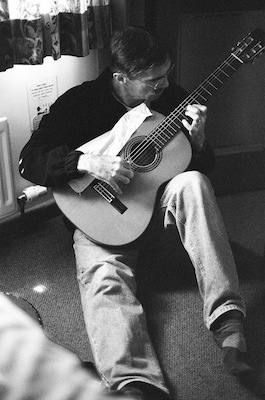

I wonder sometimes what some of my co-workers would make of my father’s multi-decade commitment to classical guitar. For as long as I can remember, he’s spent regular evening sessions practicing, composing, and refining his strumming technique (classical guitarists use carefully grown and groomed fingernails instead of a pick to pluck the strings). As a child, I remember falling asleep to the sound of him practicing versions of “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” or “I’ll Fly Away” arranged by a Christian classical guitarist he liked named Rick Foster.

Photo by Anna BroadwayEven in elementary school I was a night owl who fell asleep long after my official bedtime. As I lay in bed in the semi-dark, whispering stories to myself and occasionally turning the pages in a paperback I’d snuck from my parents’ library and kept hidden beneath a pillow for this purpose, Dad’s guitar playing often provided a soundtrack for at least 15 or 20 minutes before he and Mom also turned in for the night.

Photo by Anna BroadwayEven in elementary school I was a night owl who fell asleep long after my official bedtime. As I lay in bed in the semi-dark, whispering stories to myself and occasionally turning the pages in a paperback I’d snuck from my parents’ library and kept hidden beneath a pillow for this purpose, Dad’s guitar playing often provided a soundtrack for at least 15 or 20 minutes before he and Mom also turned in for the night.

In those days, he might have still been taking private lessons from a professional guitarist who taught out of a studio in nearby Seattle. We kids soon learned the necessary accoutrements for the occasional Sundays when Dad helped with the music at church: the slim, stainless steel music stand whose wires could never hold more than a few pages in place and the grooved, green footstool that supported Dad’s left foot when he played. (I’ve never seen a classical guitarist in concert, but I wonder what the performance-grade foot stand looks like: do they modify the stage with a small, special riser there? Is it painted a dull black for concealment? Or would the Liberace of classical guitar bling his out with rhinestones?)

Dad’s footstool was adjustable, so we kids could lower it several notches for the guitar lessons he gave us as one of his contributions to our homeschool education. None of us ever caught his full-blown passion for the instrument, though. At best we can affirm it. Dad’s guitar has accompanied him on so many vacations and family trips that a few years back, we kids finally decided to replace his heavy, battered case featuring a macramé carrying cord (Mom made it herself) with a lighter version that boasted a more ergonomic handle.

For a long time, Dad focused on refining his technique and tried to learn songs he’d come to love from recordings by his favorite classical guitarists, chief among whom was Christopher Parkening. But the year I turned 13, my maternal grandparents celebrated their 50-year anniversary, and Dad decided to write a song for them.

Though none of us four kids (and soon-to-be performers of this song) could remember Dad composing before, it turned out that he’d written a simple but memorable praise song, beloved by some of Mom’s nieces from the years when Dad was courting Mom and still a fairly new Christian. One summer when their family made the annual drive up to Washington state from their home in Dallas, those five older cousins learned the song from their aunt’s new boyfriend. It’s endeared him to them ever since.

Even today, those cousins ask Dad to play “The Bird Song,” as we all know it, whenever a now rare occasion brings us together. A few years ago, I sat next to one cousin’s daughter singing something quietly to herself, and I realized only a few bars in that I knew the song . . . and its composer . . . quite well. Those five girls never forgot the song, and they have taught it to their children.

For whatever reason, though — whether because he and my mom went on to have four kids in five years, or because said births also coincided with his completing two degrees in the first nine years of their marriage — Dad took a long hiatus from composing after “The Bird Song.”

With the “50-Year Love Song,” as he called my grandparents’ anniversary song, that all changed. Throughout the two decades since, Dad has continued to write pretty regularly. If he’s not actively working on a song at present, he probably finished one not long ago, or he’s noodling away at the motifs he’ll draw together for a new song in the future. He’s written for church retreats, the graduation of my siblings, in response to the illness or death of friends . . . even a song about his trying years as a 50-something struggling to earn his PhD in engineering.

In the years since I left home, I’ve met many other people who play an instrument, but most either do so in some kind of professional capacity (even if that means occasional gigs and a day job) or they aspire to do something more serious, which usually means a recording of some kind. I say that not to disparage their ambitions, but as a contrast to what “serious” musicianship means for my dad.

On a recent visit to see my parents, Dad confided how a change in the way he cuts and sands his plucking nails has improved the quality of his tone. He made the change based on a technique he’d read about in an interview with a professional like Parkening or someone from the L.A. Guitar Quartet.

Dad, too, has made recordings of his songs — even investing in progressively better technology to do so — but he does that to help him in the composing process as well as for posterity and gifts for family and friends.

Hearing him now, on my occasional visits home, I’m always struck by how good he sounds. Sometimes I tell him that if he ever wanted to, and could find a bass player and violinist to accompany him, he could probably do jazz trio gigs at restaurants or coffee shops that like local performers.

But Dad has never struck me as ambitious for a larger audience. He seems content to quietly excel in the midst of those he loves, works, and worships with. Their delight, coupled with his Maker’s and his own, suffices somehow.

Watching my fellow, white-collar professionals go about their lives via cell phone, I sometimes wonder what they would do if imprisoned, marooned on an island, or just stranded without Internet or a working TV. “What ordinary people once made, they buy; and what they once fixed for themselves, they replace entirely or hire an expert to repair,” Matthew B. Crawford writes in Shop Class as Soulcraft. In a real crisis, cut off from those who sew on their buttons, sing their favorite songs, bake their bread, and construct the furniture they sit on . . . how would my coworkers survive?

I’ve seen three separate exhibits of art by prisoners — two from American internment camps for the Japanese, one from European camps on the Isle of Mann. All included paintings and drawings made on available materials, like newspapers or sheets of cardboard torn from boxes. Some prisoners at one of the Isle of Mann camps even found a way to construct furniture (which I believe had been their trade before the war). The French composer Olivier Messiaen actually composed his “Quartet for the End of Time” while held in a Nazi prison. He and three other musicians he’d met in the camp premiered the work there for their fellow prisoners and guards.

When freedom and dignity suffer the worst threat, the response of those who survive seems to involve reclaiming and reasserting their humanity through their eyes, noses, hands, tongues, voices, and imaginations. But what about those of us who store our lives in the cloud and outsource all but the most intimate bodily activities to skilled “professionals”?

A couple years ago, I read sociologist Christian Smith’s book Lost in Translation, which looks at the religious lives of young adults. In it, he paints a rather grim picture: a generation that mainly sees work as a source of money, which one apparently spends on belongings like those they presumably see on TV all the time, for hours on end each day. Though Smith and his fellow authors didn’t emphasize this point, I had difficulty finding in their account much evidence that their subjects had experienced art or many of the joys of physical crafts or activities, aside from sex and drinking.

Yet if fully experienced humanity requires the data each sense provides, the whole body’s engagement with the people and world around us, what happens when we outsource more and more skills to others, reclassifying learnable traits and activities as professions?

Now, certainly I am grateful for the cheerful mechanic who diagnosed and replaced my broken alternator last Christmas Eve. And I owe a great deal to the tailor who salvaged the almost-brand new red leather shoes I’d spilled jojoba oil on. But that does not diminish my own satisfaction from improvising an oil plug gasket by sewing together part of a leftover ring from a battery-cleaning kit. Nor does it dim the delight of successfully building a new pad for a seatless chair frame I found on the street.

Many things take experts, yes. And for their years of skill and experience, I’m happy to remunerate them. But some skills I’ve found it worthwhile to learn myself, even if in passable fashion. “To fix one’s own car is not merely to use up time, it is to have a different experience of time, one’s car, and of oneself,” writes Crawford.

A few months ago, I convened several friends to sightread through Beck Hansen’s new, sheet music only “album” Song Reader. We formed an uneven ensemble, to be sure. I, as the primary pianist, may have hit more bad notes than right ones. I’m sure the few professional musicians among us suffered many moments of private horror at how ineptly we managed things.

And yet, despite all the inequity in skill and uneven efforts at prior practice, there were moments when we almost found a groove and the song’s potential began to shine through. Though I nearly wince every time I hear the recordings again, something magic happened among we few musicians and the friends and neighbors we’d gathered that warm, June Friday night.

We made our own entertainment. In doing so, we made something more than that.

Anna Broadway is a writer and web editor based near San Francisco. The author of Sexless in the City: A Memoir of Reluctant Chastity, she has written for TheAtlantic.com, Books and Culture, and Paste.