On Songs and Stories: Tokens of Knowledge in Another, Deeper, Rarer Form

Sometimes words keep circling back-and-around a person’s life. For example, it was at the Art House that I first asked this question, “Can you sing songs shaped by the truest truths of the universe, but in a language that the whole world can understand?”

Charlie Peacock, Steve Turner, and I were speaking to a group of 50 or so young musicians who all had some kind of relationship to Charlie’s vision for music, the culture, and the world. In one of the sessions I asked that question, and I have been asking it far and wide ever since. It seems the right one, or at least one of the right ones. It is not enough to know what you believe about God and the world, or to be able to communicate that to people who see life as you do. The harder work is to develop the habits of heart that form the skills which allow us to communicate with everyone, with Everyman and Everywoman.

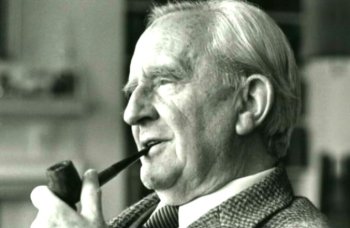

We celebrate the artfulness of Tolkien and his unusual ability to write for the whole world. A deeply thoughtful Christian, a very committed father, an unusually gifted professor — along the way he began to wonder about hobbits. First he told his tales to his children, delighting them with the story of Bilbo and his adventures. Over time he began putting the story to pen and paper, and read it aloud to his friends around a corner table at the Eagle and the Child. Finally, he found a publisher, and the rest is history.

A story of cosmic conflict, with painfully clay-footed hobbits given the task of affecting the way the world would turn out, Tolkien’s literary vision has changed the way we think and live: schools and schooling, films and books, even the marketplace. My wife and I were part of the founding of Rivendell School in Virginia over 20 years ago, a place where — in Tolkien’s own words — we hoped that “duty and desire would someday meet.” The global phenomenon of The Lord of the Rings films — blockbusters in every sense — achieved both popular and critical acclaim. It is not possible to walk into a good bookstore anywhere in the world and not find his books making money for booksellers of all sorts. While “shaped by the truest truths of the universe,” Tolkien’s work is written in a language that everyone can understand — whether one believes in the Nicene Creed or not.

Tolkien and his friends — the Inklings as they called themselves — together created a community of practice which over time has shaped the moral imagination of generations. Young and old alike have loved the worlds the Inklings created, as they have allowed us to love our world more fully. That is perhaps the best of art, and the best of life.

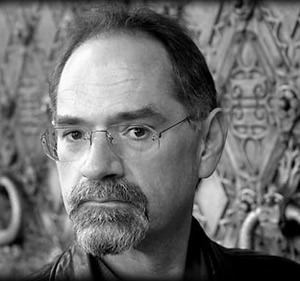

One of those drawn into this vision is the novelist Stephen Lawhead. An American, he moved to Oxford 25 years ago to breathe in the air of the Inklings, and he began writing about the Celtic lore that stands behind all things that we know as Welsh, Scottish, and Irish—and on some tellings, perhaps even British.

In a certain way, Lawhead’s is a good story to tell in light of the story that is the Art House and its vision — the briefest and sketchiest of histories. Charlie and Andi met in high school, and began their life together in the jazz and fusion scene of northern California in the 1970s. With their move to Nashville and the purchase of the 100-year-old country church that became the Art House, early on it was a haven for anyone looking for alternatives to status quo models of what it meant to be a Christian and an artist. Some of these folks were deeply embedded in what was then known as the Contemporary Christian Music industry. But over time Charlie began to wonder about the music that was in its heart. As he put it in his book At the Crossroads, we know we can make money singing songs to each other — but should we? For him the question was never born of arrogance or contention, but more as one of the most respected voices in the community. Having come from the mainstream pop world, he was championed by the CCM industry and became a respected producer of some of its best music. But it was never his home, and he soon came to the conclusion that there was another kind of music yet to be done.

If dcTalk meant one thing musically — gifted, able, entrepreneurial as they were, singing songs for the church — then Switchfoot has meant something else, taking their music into a culture that they understand with surprising intuition, offering songs that play across the cultures. And Charlie’s work with other bands continues on, keeping him very busy, working with them to sing songs that the whole world understands, and likes.

But this business of translating is hard. I confess that the first time I saw a Lawhead novel, I was suspicious. I knew that he had come from Wheaton and the Christian publishing industry. My radar was “up.” When I began reading Taliesin, the first of his Pendragon novels (the story of the Arthurian legend), I was ready to put it down if he disappointed me, if he “cheated” by forcing a “Christian gloss” on the story that did not fit, that did not have integrity. Sorrowfully, “Christian art” is too often known for this problem.

Lawhead surprised me. After reading Taliesin, I read Merlin, and then Arthur, and on through the series. Fairly sure that he could not keep it up, I didn’t read anymore for a while. But in a bookstore I saw Byzantium, Lawhead’s story of the Irish monk who takes the Book of Kells from Ireland to Byzantium, the capital city of the world at that point, offering it as a gift to the Emperor of the World, for whom the book had been made. Lawhead imaginatively created a world with genuine complexity, drawing on the contours of a history that is all of ours, though I did think that the very end the story was less than it ought to be. (I remember talking with novelist Tom Wolfe about his work, and he looked back across the table and said to me, “I don’t finish my novels very well, do I?” If that is true of him, it can sometimes be true of Lawhead, too.)

My reading of Lawhead’s novels has now taken me through The Song of Albion, a trilogy exploring in one more way the ancient Celtic world that lies underneath and behind our modern world. Again, the last pages were a small disappointment to me. It is hard to finish well, whether in life or in literature!

But I found Patrick next, the story of “the son of Ireland” as he is named in the book, and here Lawhead offers a surprising, richly-drawn account of Patrick’s early years — from his boyhood on the coast of what we now call England, on into his years of captivity and slavery in Ireland, and finally to his decision to return to Eire, and to the story that most know much better. Along the way we are asked to think through the common graces of premodern life, with human beings longing to make sense of the world in which they live. The ways in which Lawhead’s Patrick connects to these deepest of longings is fascinating and believable.

A few days ago I finished another trilogy of Lawhead’s, a retelling of the Robin Hood legend. Like every other book I have read by Lawhead, he does his homework and remains faithful to the history, language, and culture of the world he imagines in and through his novels. That matters, at least for the “smell test” (i.e., does it sound right? Does it feel right? Or am I being manipulated by the author to step into a world that I cannot imagine, that I am sure would never exist?) One of the persistent themes in Lawhead’s writing is his willingness to allow the reality of the yet-but-not-yet to thread its way through his stories. Honorable dreams are dreamed, and awful tragedies happen. Love is lost, found, and lost again. And without being “cheap,” when all is said and done, his books offer a redemptive vision of human life under the sun, and I honor that.

It is not, of course, that we require the details of our stories to reflect with photographic agility the worlds that we know. Hobbits, for example. Or Aslan, talking beasts, and magical wardrobes. But rather, as Walker Percy has so very wisely argued, it is more about truth, and whether our stories tell the truth. In his essay “Another Message in the Bottle” in the collection Signposts in a Strange Land, Percy wrote, “Bad books always lie. They lie most of all about the human condition.” When we groan in a story — whether the story comes to us on stage, in a novel, or on the screen — we do so, more often than not, because we feel that the writer cheated, that the narrative asks us to believe something about who we are that simply cannot be true, that will never be true.

I love Percy and his corpus, reading and rereading the stories of Will Barrett and Tom More, finding myself in these characters whose lives are so far from mine in most every way. And yet in pondering his imaginatively-drawn depiction of life, I am sure that he knows me, too.

I looked far and wide for an old (really old) collection of Dickens and found one from 1871 because I enjoy reading and rereading about Tiny Tim and David Copperfield, always certain that the world that Dickens saw is the same one that I see. And similarly with an early collection of Tolstoy, one that includes not only his well-known longer works but his short stories, too, I think about the world in which I live and know that Tolstoy lived in it as well. The same is true for the long shelf which belongs to Wendell Berry. I rarely go anywhere without taking him with me — teaching a course at a college or a seminary, giving a lecture or a series of talks, engaging someone somewhere in something that matters. Berry’s understanding of life makes sense of life — way beyond the front porch of his farmhouse on the banks of the Kentucky River.

Each of these authors tell the truth about the human condition, so their books are “good” in the deepest and truest sense. Not ever moralizing, so that we feel the authors are cheating, insisting on a “Christian” voice that does not belong in the story, or even worse perhaps, a revising of honest faith that does not allow for the breadth and depth of human existence, glories and shames that we are. In fact, these authors are suspicious themselves of bad faith and expose hypocrisy wherever its head is raised.

Yes, there are words and ideas and names that keep circling back, giving continuity to life. Charlie Peacock is like that for me. A few weeks ago he and I were together in Nashville at the biannual Wedgwood Circle gathering. My role in this story is always the professor, "the facilitator of meaning,” so I was asked to muse over the meaning of our work together, at the beginning, middle, and end. As we concluded, I told the gathering about Lawhead. He’s like Tolkien, I explained: one cannot go into a good bookstore without finding Lawhead’s novels. They have not been blockbusters like Tolkien’s, but the comparison is unfair. It would be like asking every musician to be Bach or Bono. Now 25 years and novels later, Lawhead publishes in mass-market paperbacks, selling widely all over the English-speaking world.

I read to them from Hood, the first of the trilogy telling the tale of Robin Hood. Like in every story of his that I have read, Lawhead weaves a fabric of life as we all know it, and without a blush there are people full of loves and lusts, angers and passions, truths and lies — some with faith and some with no faith, just like life on everyone’s street, and in everyone’s city. His are stories that everyone understands because they tell the truth about the human condition.

Hear these words — for every reader, yes — but for artists, too:

"One night, Bran realized that he had not heard such tales since he was a child. This, he thought, was why the songs touched him so deeply. Not since the death of his mother had anyone sung to him. This is why he listened to them all with the same awed attention. Caught up in the stories, he lived them as they took life within him . . .

As Bran’s knowledge grew, so did his appreciation of the stories themselves. He began to behold possibilities and portents, glimmerings of distant hope, flashes of miracle. The things he heard in Angharad’s songs were more than mere fancy — the stuff itinerant minstrels plied — they were tokens of knowledge in another, deeper, rarer form. Perhaps they were even a form of power, but one long dormant. At the very least, these songs were markers along a sacred and ancient pathway that led deep into the heart of the land and its people — his land, his people — a spirit and life that would be crushed out of existence beneath the heavy, unfeeling rule of the cold-hearted Ffreinc."

The story stands on its own, and yet in reading these words by Lawhead I understood again the longing that brought the Art House into being, viz. to nourish artistic visions and vocations where songs touch people "so deeply," ones that are "tokens of knowledge in another, deeper, rarer form." Charlie and Andi, and the wider community that is the Art House, have given themselves to calling into being this kind of music, this kind of art — songs that are shaped by the truest truths of the universe, but in a language that the whole world can understand.