Photograph by Judith Hougen

Photograph by Judith Hougen

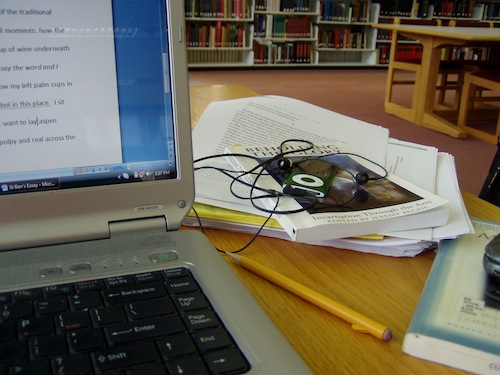

It is early August, and I am on the second floor of the university library on the campus where I teach. The school grounds rise lush and full after so much generosity of heat and rain and light, beauty now pouring in through the floor-to-ceiling window next to my table. The deserted floor is stillness, save my hive of the mind, as I work over an essay begun two summers ago, trying to conjure its closure, engaging in the slow, steady work of knitting together these little pictures of the world, of life.

I began this writing project — a book-length collection of literary essays on faith and writing — during a sabbatical four years ago. The project has ebbed and flowed, drifted through certainty and doubt, call and confusion. In the last six months, my proposal has been rejected by a handful of agents — unsurprising, really. I know this project is a hard sell.

A pencil fidgets in my hand, tapping my yellow legal pad. There is so much difficulty in the saying of things as I scratch away at sentences in this room, alone, windowed away from summer. My first paycheck of August reflects this year's teaching contract — vast diminishment, a pay cut I requested that felt like a spiritual call to buy time. But everything slows now — sleepy words and thoughts — and nothing about these essays, their future, is remotely clear. I don’t even know how the one scattered on this table will end.

I look up. The library's emotionless air and light remain a hymn of constancy, and all around me, the rows of books darken the spaces between shelves.

* * *

The Catholics have a word for these places — liminal space, liminal from the Latin meaning threshold — in times of hard transition, in the awkward footing between old and new, in lives pressed toward change, whether birth or death. It is a time of disequilibrium, imbalance, teetering at the edge of the unknown. Liminality is marked by darkness, a lack of control, yet spiritual guides call it sacred space where the only genuine transformation occurs.

* * *

My mother has cancer. Almost eleven months ago, in October, she was given three to six months to live. In those first months, I wept and waited, last fall semester a nightmare, deep breaths to pull myself together in classroom doorways, my brain on a numbing kind of auto-pilot, grief coursing through me like electricity. All that passed, calming into Christmas, spring, and now late summer, and she remains reasonably stable. The hospice nurse visits weekly and is not concerned. We are completely off the given medical maps.

When I decided to bring meals over more regularly, I began internet searches for recipes, needing dishes beyond my personal throw-together style, tapping in search terms like "chicken noodle casserole" or "easy stroganoff." I bought a bigger Crock-Pot and bottles of wine for cooking, filling my refrigerator with good cuts of beef, shallots, and mushrooms. When I stand in my small kitchen, carefully measuring and splicing together all the ingredients in a frying pan, it feels like purchasing goodness or hope.

Tonight, we sit together, my mother, father, and I, in the small dining room, surrounded by antiqued-flower wallpaper, and eat beef short ribs that simmered for seven hours in a Cabernet sauce, with pilaf and field-fresh Minnesota corn, chatting amid the satisfying clink of silverware against plates, as applause and ticking roulette spins of Wheel of Fortune resound from the small TV on the credenza. Day wanes and the light summer air in the room gentles everything, and for a minute, it's as if little time has passed, and we are all younger, wooled away from terrors of every kind. A little island of grace.

But after the serving and the cleaning, as I prepare to depart for home with darkness glazing the living room windows, I wonder how I can leave these two fragile people embracing me by the front door, and then I feel it, the edges of the painful in-between, this shadowland where we find ourselves, sharp and distinct, this place of vulnerability and hard thresholds.

* * *

Catholic priest and author Richard Rohr explains liminal space: "It is when you have left the tried and true, but have not yet been able to replace it with anything else. It is when you are finally out of the way. It is when you are between your old comfort zone and any possible new answer. . . . These thresholds of waiting and not knowing our 'next' are everywhere in life and they are inevitable. If you are not trained in how to hold anxiety, how to live with ambiguity, how to entrust and wait, you will run . . . anything to flee this terrible cloud of unknowing."

* * *

I climb into my Toyota and turn the key for the drive home, the illuminations from my car the only light on my parents' lampless street. I cue my Innocence Mission Pandora station, as I often do when leaving their home, wrapping the ride in a wistful, melancholy comfort. Exiting into Northeast Minneapolis, my car rolls toward the stoplight just before the railroad bridge, when "Snow" comes on . . .

I go out in the morning snow

in my pajamas and my winter coat

And take from the house our darker thoughts

And take away the memory of loss

And if I drop them into the snow

Will we never find them anymore?

and I let the words sing my grief into solidity. While the car idles at the light, a train rhythms over the bridge, the rumble of dark, secret cars winding across my windshield, glimpsed, then gone.

I think about the passings to come, the uncertainty I hold in this long journey with words, wanting to fully embrace the dim thresholds I’m given. Sometimes, there is a bone-deep loneliness to these moments, a lostness that buries me in the dusk of the car's interior.

* * *

I believe that our lives, our stories, are ultimately meaningful. We are marooned in time, and within our ever-evolving pilgrim way, there is a strange goodness in the places where we learn to hold the faint mysteries of the eternal while at the brink of earthly affliction and darkness. With nowhere else to go, liminal space bids us to anchor ourselves in the present moment, to hold the anxious tensions, to see and feel and love more deeply the beautiful and broken world around us.

* * *

The library closes soon, so I push back from the table and gather up my books and papers, the essay’s ending still unformed but closer. I am achy, a little foggy and discouraged, but I know making art is part of the ongoing work of meaning in my life. I shrug my messenger bag onto my shoulder and walk the long aisle past the stacks, the oversized art collection, thousands of books standing at attention. I head toward the stairs and back into the hot breath of summer.

In a time threaded with liminality, all I have to offer is my finite, fallible self, my defenseless skin, and I try to hold onto my capacity to be faithful to the inexhaustible opening of time and whatever glories or agonies attend it. I think about the coming months, this precarious stretch, my parents and my infamous traveling Crock-Pot, the urgencies of art, stacks of sentences that require me to wrap myself around silence and suffering and joy's quiet possibilities so closely that I recognize myself in every note of grandeur and desolation.

Classes begin in a few weeks, and this quiet campus will soon be teeming. The deep green will give way to autumn, to things I can’t picture. I know liminal space invites me to a larger place of trust in God, and most days I desire to live into that. Car keys in hand, I unlock the door, listening a little harder, more readied for mystery — perhaps this is the grace of the journey.

Judith Hougen is the author of a collection of poetry (The Second Thing I Remember) and a spiritual formation book (Transformed into Fire). She teaches writing at the University of Northwestern in St. Paul, Minnesota. When not spending inordinate amounts of time in coffee shops, she blogs about spirituality and writing at Coracle Journeys.