The first time I realized that I loved Theodore Roosevelt was when I learned that he had once read Anna Karenina while navigating the Dakota wilderness. I loved him even more when I later discovered that at the time he was aboard a boat he built from scratch, and he was floating through a nearly impassible ice dam in below-freezing temperatures, and he was reading aloud in order to entertain his two boating companions and three thieves whom he had just captured because they had stolen his original boat six days before.

The first time I realized that I loved Theodore Roosevelt was when I learned that he had once read Anna Karenina while navigating the Dakota wilderness. I loved him even more when I later discovered that at the time he was aboard a boat he built from scratch, and he was floating through a nearly impassible ice dam in below-freezing temperatures, and he was reading aloud in order to entertain his two boating companions and three thieves whom he had just captured because they had stolen his original boat six days before.

When I was little I wasn’t sure if I wanted to grow up to be a scholar or an adventurer. Then, when I was about eight, I picked up a skinny paperback biography called Bully for You, Teddy Roosevelt! From that day on Roosevelt became my rollicking older cousin who I would follow anywhere, both to the library and the wilderness beyond. After that I started reading books while perched in oak trees and quoting poetry while riding my bicycle.

One autumn in college, I visited Theodore Roosevelt’s long-time home—now a museum—in New York. My roommate and I drove from her family’s home in Forest Hills to the regal, wooded town of Oyster Bay, Long Island. We ate maple cream cookies and rolled down the windows. The air smelled of sea salt and the spicy, fecund scent of dying leaves. Like Roosevelt himself, the house on Sagamore Hill is bigger than it looks initially. It is sturdy and compact, not long or lithe, and lacks the Victorian frills of many houses of the time. It is a stocky house, and jolly, with a front porch as wide as Roosevelt’s grin.

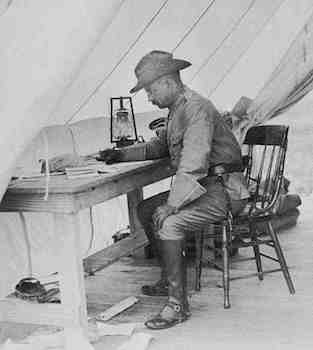

The interior of the house has not changed significantly since Roosevelt’s death. The rooms are set up as if for use; Roosevelt’s chair is at his desk; the kitchen looks ready for cooking. The back room boasts a tall, arched ceiling of dark, rich wood. The whole house looks both scholarly and strapping, literary and vigorous. Bearskin rugs stretch out under shelves of books. Roosevelt’s waste paper basket is made of an elephant foot.

After my visit, I purchased Theodore Roosevelt’s Letters to His Children. This collection proved an apt guidebook to Sagamore Hill; I immediately felt I’d been inaugurated into the culture of Roosevelt’s family life. The letters are playful and personal, full of anecdotes and advice, stories of outdoor adventures and contemplations on politics and literature.

In one letter, Roosevelt writes to his son Kermit about studying Latin and playing football, all in the same paragraph. In others he tells of exploring Rock Creek with the children, and reading The Last of the Mohicans to them at bedtime. Sagamore Hill was a place for verbal and physical spars—riotous dinner parties, boxing matches, presidential visits, pillow fights. A number of absurd pets roamed the grounds—horses, dogs, a blue macaw, and a bear named Jonathan Edwards.

In one letter dated August 16, 1903, Roosevelt describes his daughter’s birthday celebration:

When Ethel had her birthday, the one entertainment for which she stipulated was that I should take part in and supervise a romp in the old barn, to which all the Roosevelt children . . . [and several friends] were to come. Of course I had not the heart to refuse; but really it seems, to put it mildly, rather odd for a stout, elderly President to be bouncing over hay-ricks in a wild effort to get to goal before an active midget of a competitor, aged nine years. However, it was really great fun. (Theodore Roosevelt’s Letters to His Children, p. 54)

The easy thing would have been to stay indoors. Roosevelt was born with weak lungs; as an asthmatic child in grimy New York City he could barely breathe. His father’s famous words—you have the mind, but not the body; you must make your body—convinced young Roosevelt to strengthen his lungs and muscles. By college he could box and hike and row crew. Despite his weak heart, he travelled extensively throughout his lifetime—to the American West, to South America, to sub-Saharan Africa. And when his children were born, he passed his father’s advice on to them. Life is richer when both the mind and the body are healthy, he told them. Building one without the other just will not do.

I have followed Cousin Roosevelt to several of his stomping-grounds—New York City, the African savannah, the Dakotas. I have not read Anna Karenina while floating through an ice dam, but I have recited Victorian poetry in the Arizona wilderness and read Aristotle in a safari tent. And perhaps more dear to me still are the romps I have taken closer to home, followed by a satisfactory flop into my own bed with a favorite book.

One of these favorite books is Roosevelt’s autobiography, in which he writes a bit about his heritage. It turns out his pet bear, Jonathan Edwards, was named for his distant ancestor, the renowned preacher. As I read this for the first time ever while lying in my New York apartment bunk bed, I was delighted—several years ago my cousin had traced our genealogy, and we, too, are descended from the line of Jonathan Edwards. Cousin Roosevelt and I may actually share blood—even if it’s just a drop—and I may follow him and his antics forever.

In 1903, while Roosevelt was in the White House, he wrote a letter to his oldest son, Ted Jr., who was sixteen years old at the time and in boarding school. He advised Ted on whether or not to pay football that year. He concluded by saying, “I need not tell you that character counts for a great deal more than either intellect or body in winning success in life” (Theodore Roosevelt’s Letters to His Children, p. 63).

When I imagine a rich and balanced life, I picture a home much like Sagamore Hill, bustling with active bodies and active minds, where faithful character above all drives the life of the family. One of Roosevelt’s most common phrases for his experiences was great fun. When mind, body, and spirit are working and growing together, life can indeed be great fun, whether on icy river waters or in the comfort of home.

Betsy Brown is a writer and teacher who lives in Arizona. She received her Master of Fine Arts in creative writing from Seattle Pacific University.