Wendell Berry may not quite be a household name. But I, for one, mention his name on a regular basis in my house, while traveling around the country, and when talking with neighborhood friends about produce, local happenings, or politics.

Wendell Berry is a farmer, writer, and preservationist from Kentucky. He splits his time between three quiet activities: 1) writing fiction, poetry, and essays, putting pen to paper (quite literally) in a tiny hut on the Kentucky river; 2) working his farm; and 3) engaging in non-violent civil disobedience supporting various humanitarian or agrarian causes. He has spoken out in his 76 years against wars, corporate corruption, nuclear power plants, the death penalty and abortion, coal mining practices, mountain top removal, and other issues of land and life. Although he doesn’t fit squarely into any one political category, just last month, President Obama awarded him the National Humanities medal. Berry is a truth-teller of the storytelling variety, an everyday man with the character of a great king, and he has profoundly stirred up my own spirit to be brave, careful, and rebellious in ways that seem rather contrary to the norm. He reminds me of the Lorax, somewhere in the middle of Dr. Suess’s children’s story, just before all the Truffula trees are gone, balancing there on a stump pleading for the Barbaloots and the Hummingfish.

Over the years, I have started several unfinished thank you letters to him in my head, or scribbled them on the pages of a journal or in the margins of his books. I’ve had a growing sense that I somehow needed to communicate to him how much his work has shaped and enlightened me. So last fall I took out some construction paper and a pen and finally made it happen. It went something like this:

Dear Mr. Berry,

I have begun this letter so many times over the years. Why is it that the most significant things we do are often the things left undone? I should have written it years ago, but here it is now . . . Your writing enables me to crave and long for the country while I live in the city. It urges me to slow down when the pace around me is whirring. And it hushes my spirit when my world is full of noise. I wanted you to know that I am one of many who has been profoundly affected by your mentoring. God speaks through your narratives. His beauty is in your poetry, your disruptive encouragement, and your written voice. May God cause your work and art to take deep root, springing up new beauties in my heart, in the hearts of my children, and in the hearts of many others.

I also told him that his writing made me wish I’d been born in a small town circa 1950, learning the ways of survival from the land and from dependence on neighbors. Though the particulars are not the same, even now while I decidedly raise my family in the city of East Nashville, Berry’s principles of interdependence and sustainability are my daily teachers. My husband and I, both singers and songwriters by trade, think of our careers and our family life as though they were a small farm. We don’t produce heirloom tomatoes, but we aim to produce melodies that go out into culture like agents of nourishment. We teach our children about the craft and economy of self-employment as we write, record, and tour. And we have much yet to learn.

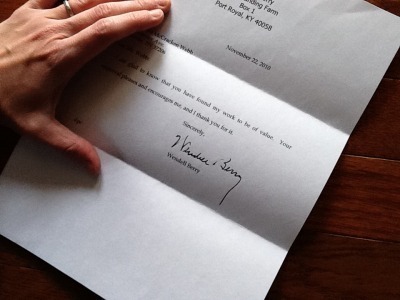

The exercise of writing my letter to Wendell Berry was, after my procrastination, a very gratifying experience. Just knowing that my official “thank you” was sealed, stamped, and on its way to Port William — I mean, Port Royal — gave me a feeling of deep satisfaction and joy. This would have been enough, but then a few months later, he wrote me a reply. I read his words of appreciation on a simple note, typed on simple stationery. I was thrilled.

The exercise of writing my letter to Wendell Berry was, after my procrastination, a very gratifying experience. Just knowing that my official “thank you” was sealed, stamped, and on its way to Port William — I mean, Port Royal — gave me a feeling of deep satisfaction and joy. This would have been enough, but then a few months later, he wrote me a reply. I read his words of appreciation on a simple note, typed on simple stationery. I was thrilled.

Around that same time, just one mile north of my house, my friend Alice had also been writing letters to Berry. She had also had a steady diet of his poetry and writings for the past few years, and she, with another mutual friend Flo, was now plotting a visit on our behalf to celebrate the birth of our friend Katy’s first baby. She thoughtfully planned the meeting as the perfect occasion for the baby’s first road trip and our shared joy as four friends. Although we have been friends for years, we rarely get this kind of uninterrupted time together. Having confirmed our visit by letter, Alice, Katy, Flo, and I loaded up in one car together on a chilly March morning for a trip to Kentucky — books, hopes, a basket of homemade things, and one celebrated baby girl in tow.

L to R: Alice, Sandra, Flo, and Katy outside of the dinerOn the drive, we read excerpts of our favorite Wendell Berry books out loud to each other and chatted about what we most wanted to ask him. Of course, our journey wouldn’t have been complete without a healthy dose of girl-talk — inevitable on a road trip without husbands. Before long, we rolled into a sleepy Port Royal that Sunday afternoon. Although it was on the map, we couldn’t believe it was actually a real place. Port Royal is a patchwork strip of storefronts, a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it sort of spot made up of a local bank, a post office, a general store with a built-in diner (with little printed signs about their town’s famous author, Wendell Berry), and an old Baptist church. I am sad to report that, like most small towns in our country, Port Royal looks as though it is dying.

L to R: Alice, Sandra, Flo, and Katy outside of the dinerOn the drive, we read excerpts of our favorite Wendell Berry books out loud to each other and chatted about what we most wanted to ask him. Of course, our journey wouldn’t have been complete without a healthy dose of girl-talk — inevitable on a road trip without husbands. Before long, we rolled into a sleepy Port Royal that Sunday afternoon. Although it was on the map, we couldn’t believe it was actually a real place. Port Royal is a patchwork strip of storefronts, a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it sort of spot made up of a local bank, a post office, a general store with a built-in diner (with little printed signs about their town’s famous author, Wendell Berry), and an old Baptist church. I am sad to report that, like most small towns in our country, Port Royal looks as though it is dying.

We then passed through the town and down a short way toward the river. We found our way to Wendell and Tanya’s address by narrative instinct. Not knowing the house number, we found their home based on his writings, our observations, and reports from friends who had made this same pilgrimage. The solar panels out in the field, the sheep, the tiny writing hut on the river, and the sloped property like the one where his famous character, Jayber Crow, lived. Even the border collie who ran out to greet us reminded me of the one in his novel Hannah Coulter. As our wheels turned over the gravel driveway, we looked up at a modest, white farmhouse set right on the hill, and we knew it was Lanes Landing Farm. I expected Disney music to burst out with glorious, warbled violins over our heads.

Tanya Berry opened the door and, without any fanfare, welcomed us into the house. We, four girls and one baby, crowded into the entryway. Wendell and Tanya both wore their church clothes. Wendell stood slightly behind the door, wearing a three-piece tweed suit. It took a second for my eyes to adjust to the light. He was taller than I expected, and he shook my hand as I came in; I, in turn, introduced myself. The overhead lights and lamps were off. The room was lit only by natural light from the windows, which seemed just enough at first, and more than plenty once you got used to it. I was surprised at how nervous I suddenly felt, wondering what to say upon first meeting someone you feel like you know but have never actually met.

Their home was beautiful in an ordinary way, with well-used furniture and tasteful modern-folk artwork adorning the mantle and walls. At one point later in our conversation, we learned that they have the same electric stove and washer they purchased in 1965. There were wood-burning stoves in each main room, producing steady warmth. The main wall in the living room was covered entirely with neat rows of books. After our introductions, we circled up to find seats around the stove and stumbled rather clumsily into conversation. Wendell didn’t seem to enjoy being the attention of our admiration but was gracious as we began to establish some common ground of conversation.

Wendell is witty and well-spoken. I have rarely experienced such rich, wide-ranging discourse within such a short time of meeting someone. He and Tanya seemed to dig in more as we shared our experience of living life together (literally within a mile or two of each other) in the city. Katy talked about her front yard garden and how the neighborhood kids thought she was magic because she could pull up carrots from dirt. We also discussed our hopes for our children’s futures and the challenges of public education where we live. Wendell and Tanya have both spent time educating their now-grown children and grandchildren, and Wendell said, “You can’t think up a future for your grandchildren. You can’t even think up a future for yourself. You’re gonna be surprised.” Somehow this comment both sobered and heartened me in the same breath.

There were many more moments like this as we talked; I couldn’t begin to convey them in one sitting. But Wendell is very quotable — he just seemed to toss out pearls of wisdom left and right. The overriding theme we discussed was neighborliness. You might not always like your neighbor, but being able to depend on one another instead of a government or corporation gives you genuine independence. Tanya chimed in with vigor, “Trade instead of buy whenever you can.” As we talked, you could see that they were of one mind in having true, good, change-making conversations about depending on community rather than corporations. “Serve your place, and allow your place to serve you.”

We talked further about the dangers of religion, the business of war, and how words like “public education,” “environment,” and “free market” have been hollowed out. We talked about the death of small towns in America, the importance of local banks, and the value of decent pleasure and joy in the midst of some potentially depressing times.

During every minute of our conversation, the Berrys were committed to saying exactly what they meant, leaving nothing to chance or nebulous romanticism. Wendell is both an idealist and pragmatist in his writing, and he is very much this way in person. At one moment he would surprise us with a gentle reprimand of our casual use of the word "love," commenting “Love is not a feeling, it’s a recipe. None of it gets interesting until it gets down to practicality.” But the next moment he would persuade us with the warmth of a benevolent teacher, reminding us of the importance of tangibility. In this increasingly connected and virtual world, he reminded us, “If it’s baby versus internet, you’re never gonna smile that way over the internet.”

One of my favorite moments was when Wendell said that he is a member of two organizations: 1) The Slow Communication Movement and 2) The Preservation of Tangibility. He noted that anyone can join these and added with a grin, “Actually, I think I founded them.”

At one point in our conversation, I had the opportunity to tell Wendell how much his phrase “the joy of sales resistance” has meant to me over the years. How this phrase has shaped my habits of buying and selling and made me more aware of what it feels like to be “bought and sold” by the pressures of consumerism. Berry said, “I try not to obey ... to buy what I don’t need.” Singer-songwriter Joe Pug says it this way in his song “Hymn #101”:

The more I buy, the more I’m bought. And the more I’m bought, the less I cost.

I realized at one point while thanking Berry for his insight that I was nearly quoting the lyrics to one of my own songs, quite by accident (how embarrassing). But then again, in my song, I was only paraphrasing him. It was a funny moment in my head of how art makes circles around us and within us, taking us to new places of discovery and then bringing us back where we started.

L to R: Sandra, Wendell Berry, Alice, Flo, Katy and her baby girl. Photo: Tanya BerryI took copious notes while we sat on that well-loved sofa in their living room. As I am not well-versed in journalism, and it felt silly at the time, I will treasure that little field notebook for years to come. After our visit, the Berrys were heading to a family birthday celebration and Wendell had to go out to bring in the sheep for the evening. He pulled a “Fred Rogers," swapping his dress shoes for Wellingtons and pulling his coveralls over his dress clothes, charmingly teasing us about having waited to take a picture until he was dressed for chores.

L to R: Sandra, Wendell Berry, Alice, Flo, Katy and her baby girl. Photo: Tanya BerryI took copious notes while we sat on that well-loved sofa in their living room. As I am not well-versed in journalism, and it felt silly at the time, I will treasure that little field notebook for years to come. After our visit, the Berrys were heading to a family birthday celebration and Wendell had to go out to bring in the sheep for the evening. He pulled a “Fred Rogers," swapping his dress shoes for Wellingtons and pulling his coveralls over his dress clothes, charmingly teasing us about having waited to take a picture until he was dressed for chores.

As we drove home that evening across the Kentucky and Tennessee countrysides, we discussed the implications of Wendell’s ideas on our daily lives. The connection between four friends living just a mile or two away from each other is actually the most significant thing he could give us in his life work. He had already given us the seed of “neighborliness” by way of his writings. Indeed, good things have taken root in our front and backyard city vegetable gardens, our children’s educations, our concern about the health of the Cumberland River, and our concern over the flourishing of Tennessee farms.

Somewhere on Highway 65, it occurred to me that ideas are only seeds until they find places to take root. It is in community that ideas become reality — fruit-bearing trees and shelter-giving plants. Our two hours with Wendell Berry himself would not have mattered were his words and writings not woven into each of us as we live life together. By reading his writings on our drive and sharing how his words have intersected with our own narratives, something full-circle happened.

This is my great hope and belief about art: it is culture-making. Do with it what you will. Poetry can change people. Story can change the world. Global good starts as tiny as a Truffula seed. And if the sun and the bees and the rain and the birds give us their graces, we could have ourselves a harvest of renewal by summer’s end.

Sandra McCracken is an independent singer-songwriter whose smart, soulful blend of folk, pop, and gospel is as progressive as it is timeless. A founding contributor to the Indelible Grace projects, McCracken's contemporary settings of classic hymns are sung in congregations across the country. Drawing inspiration from Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash, Emmylou Harris, and U2, McCracken crafts songs that wed razor-sharp hooks with incisive, confessional lyrics to create a transcendent portrait of the human spirit. McCracken currently lives, writes, and records at her home in East Nashville, Tennessee, with her husband, Derek Webb, and their two children.