Never mind that this child is in a different country than the one for which we have been approved. Never mind that moving forward with this child will mean redoing much of our paperwork, once again driving around to banks, doctor’s offices, police departments, and myriad government buildings to get new documents printed, notarized, and certified. My friend Jill has a song that sings, “And then out of nothing, it’s telling me something I didn’t know that I knew.” There is a mysterious kind of knowing that can happen to a person, and it seems all the more sweet and supernatural when it comes to your life partner in the same time and space.

All in Hospitality

We didn't totally understand what Communion was. At least I didn’t. If it was magical to the Catholics, literally becoming body, and blood, and meaningless to atheists, a bizarre religious ritual, I suppose I fell somewhere in between. We read no books about Communion, took no classes to prepare, made no declarations of faith besides the act itself. Now I see the act is its own declaration, its own remembrance. But I didn't know then.

We didn't totally understand what Communion was. At least I didn’t. If it was magical to the Catholics, literally becoming body, and blood, and meaningless to atheists, a bizarre religious ritual, I suppose I fell somewhere in between. We read no books about Communion, took no classes to prepare, made no declarations of faith besides the act itself. Now I see the act is its own declaration, its own remembrance. But I didn't know then.

. . . so much of what Doll taught me had to do with working around missteps — my own, and others’ — with flexibility and grace. And, posthumously, that she’s redefined the meaning of hospitality for me, so that I think of it not only in its traditional sense, but also in the day-to-day as I “host” my children, their friends, my husband, and our friends and family. Doll cared for and catered to her guests. She hoped to spoil them with the best of what she had to offer — a thing that, when translated, came down to great love and a capacity to supply equal amounts of comfort and whimsy.

. . . so much of what Doll taught me had to do with working around missteps — my own, and others’ — with flexibility and grace. And, posthumously, that she’s redefined the meaning of hospitality for me, so that I think of it not only in its traditional sense, but also in the day-to-day as I “host” my children, their friends, my husband, and our friends and family. Doll cared for and catered to her guests. She hoped to spoil them with the best of what she had to offer — a thing that, when translated, came down to great love and a capacity to supply equal amounts of comfort and whimsy.

Find the Good and Praise It

Like it or not, I have been fine-tuned since childhood to feel the weight of the world’s woes more than most, perhaps like you who read the Art House America Blog (or write for it). Luci Shaw calls it the poet’s curse, this heightened sensitivity to life’s joys and sorrows. We can’t not feel what we feel. I couldn’t agree more and yet the nagging question for me comes down to this: how do we find the good and praise it in the midst of so much suffering? How do we flesh out our callings with lives of deep joy and courage? These questions haunt me year after year. I can’t promise much in the way of satisfying answers, only glimmers, a semblance of peace.

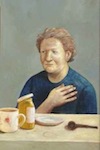

She straightened herself up, turned to face me, and put her right hand over her left — a portrait of dignity and poise. And then, with just the two of us in the room, she began to sing over me.

She straightened herself up, turned to face me, and put her right hand over her left — a portrait of dignity and poise. And then, with just the two of us in the room, she began to sing over me.

“Happy birthday to you. Happy birthday to you. Happy birthday, dear Mr. Ramsey. Happy birthday to you.”

Then she smiled, turned, and left the room.

And I wept.

Sometimes I am frustrated with the way my denominational tribe approaches the Lord's table. (Sometimes I am frustrated with the ways single people are invisible in the church.) Occasionally I sneak off for what I call "a maintenance dose of liturgy," to a place where everything in the service builds to the table, and we literally approach it, getting up out of our seats and walking to it and holding out our hands. (Occasionally I sneak off to someplace where I expect to be invisible.) I did that a few Sundays ago.

Sometimes I am frustrated with the way my denominational tribe approaches the Lord's table. (Sometimes I am frustrated with the ways single people are invisible in the church.) Occasionally I sneak off for what I call "a maintenance dose of liturgy," to a place where everything in the service builds to the table, and we literally approach it, getting up out of our seats and walking to it and holding out our hands. (Occasionally I sneak off to someplace where I expect to be invisible.) I did that a few Sundays ago.

Hospitality begins with homemaking, and proper homemaking is always connected to hospitality. The slow roll of daily tasks, like scrubbing the toilets and sweeping the floors. The seasonal study of vegetables and how they might come together for a meal. The predictable safety of steady care among housemates. And then you want others — non-residents, the stranger the better — to enjoy what you enjoy. You want to extend to others whatever provisions and comforts belong to your household. Even introverts may find that it feels natural to make home in this way. Hospitality is the art of homemaking for people who don’t belong to your home.

Hospitality begins with homemaking, and proper homemaking is always connected to hospitality. The slow roll of daily tasks, like scrubbing the toilets and sweeping the floors. The seasonal study of vegetables and how they might come together for a meal. The predictable safety of steady care among housemates. And then you want others — non-residents, the stranger the better — to enjoy what you enjoy. You want to extend to others whatever provisions and comforts belong to your household. Even introverts may find that it feels natural to make home in this way. Hospitality is the art of homemaking for people who don’t belong to your home.

Waters of Refreshing and the Joy of the Heirloom Tomato

The watering came in unexpected ways. Sometimes the Lord’s refreshing comes through a change of scenery — the resting place of a vacation, a Sabbath day of ceasing our worry and work, a retreat at Laity Lodge. Sometimes it comes through a change of countenance — we are literally righted from the inside out, brought to clarity, given new perspective and strength. Sometimes we’re made compassionate again, given a new imagination and concern for people’s needs, or a renewed sense of meaning and purpose.

I value the domestic arts. I believe in the importance of beauty, whether that beauty is in the form of a poem or a child’s first birthday cake. Yet, I have recently arrived at a place where the things I have learned, the skills I have practiced, and the supplies I have hoarded in kitchen cabinets and over-stuffed drawers are no longer helping me to create this precious thing called hospitality.

I value the domestic arts. I believe in the importance of beauty, whether that beauty is in the form of a poem or a child’s first birthday cake. Yet, I have recently arrived at a place where the things I have learned, the skills I have practiced, and the supplies I have hoarded in kitchen cabinets and over-stuffed drawers are no longer helping me to create this precious thing called hospitality.

It’s hard to tell whether this clay was accidentally or intentionally smashed. The pieces have been fitted back together, and the fault lines are visible, but the glue is not. Iridescent stone beads adorn some of the cracks, where a little bit of pot is missing. Some shards were individually painted before they rejoined their places. It looks like people worked together to restore it. It’s no good for holding water now, but it can’t hold dark any more either. Where the water would pour out, light pours in.

It’s hard to tell whether this clay was accidentally or intentionally smashed. The pieces have been fitted back together, and the fault lines are visible, but the glue is not. Iridescent stone beads adorn some of the cracks, where a little bit of pot is missing. Some shards were individually painted before they rejoined their places. It looks like people worked together to restore it. It’s no good for holding water now, but it can’t hold dark any more either. Where the water would pour out, light pours in.

Writing a letter to a stranger is all about trust. To offer your thoughts and opinions, some of which you might never say out loud, is truly relationship building. But there’s also something refreshing about writing to someone who is not fully aware of your daily life, your flaws, the way you look, or how cute your children are. They get a totally different picture of things, which makes the whole thing special. Our relationship took awhile to gain traction, and it was about a year before Michelle and I got to the meat and potatoes of things. Now I feel comfortable writing to her about just about anything, including some things I might never say out loud to people in my daily life.

Writing a letter to a stranger is all about trust. To offer your thoughts and opinions, some of which you might never say out loud, is truly relationship building. But there’s also something refreshing about writing to someone who is not fully aware of your daily life, your flaws, the way you look, or how cute your children are. They get a totally different picture of things, which makes the whole thing special. Our relationship took awhile to gain traction, and it was about a year before Michelle and I got to the meat and potatoes of things. Now I feel comfortable writing to her about just about anything, including some things I might never say out loud to people in my daily life.

Epiphany

It is hard to come here and not feel guilty. So I come bearing gifts: a bag of navel oranges and three pairs of warm socks (from my overstuffed drawer, yes, but clean and only slightly worn). In the morning they will all be snatched up, along with half of the oranges. Meanwhile, I stand outside in the dark and drizzle under the lamplight, waiting to be let in. My pillow’s stuffed in a white trash bag as deep blue splats form on my sleeping bag. It’s 11:00 p.m., January 6.

There are only four women staying at the shelter tonight, Maria tells me. Should be pretty quiet.

We lived under the same roof for less than two months. The short time gave us many answers to the question, “What makes a house a home?” Shared meals and laughter became the foundation. Courage to tell each other our hard life experiences formed a beautiful entryway. Talking while cooking and cleaning side by side put up an internal framework that remains.

We lived under the same roof for less than two months. The short time gave us many answers to the question, “What makes a house a home?” Shared meals and laughter became the foundation. Courage to tell each other our hard life experiences formed a beautiful entryway. Talking while cooking and cleaning side by side put up an internal framework that remains.

Philip woke at eight the next morning and started the percolator. Around nine we decided that we wanted to treat everyone to coffee in their rooms, so I assembled the trays with pretty mugs and sprigs of holly and cream and sugar and, each carrying one, we ascended the stairs, grinning at one another like children. We delivered their coffee with bright greetings, and Philip started the fires in their rooms so that they could relax in bed for a while before breakfast. I told them we would eat in an hour: already the sacrosanct aromas of my mother’s Christmas Morning Breakfast Casserole, reserved for only the most special of occasions, was filling the air with invitation.

Philip woke at eight the next morning and started the percolator. Around nine we decided that we wanted to treat everyone to coffee in their rooms, so I assembled the trays with pretty mugs and sprigs of holly and cream and sugar and, each carrying one, we ascended the stairs, grinning at one another like children. We delivered their coffee with bright greetings, and Philip started the fires in their rooms so that they could relax in bed for a while before breakfast. I told them we would eat in an hour: already the sacrosanct aromas of my mother’s Christmas Morning Breakfast Casserole, reserved for only the most special of occasions, was filling the air with invitation.

Fruitcake lovers tend to be quiet whereas fruitcake haters tend to be loud, but most fruitcake haters I know have never had good fruitcake (and some have never had any fruitcake at all). So it seems that makers of fruitcake either must either hide their wares under a bushel (no!) or share them with evangelical fervor. Thus, I have decided to become an evangelist for fruitcake. Because everyone (especially my brother-in-law who requires more prayer, for he has yet to refrain from making disparaging remarks while the rest of us groan and ask for more) needs to know how wonderful it is.

Fruitcake lovers tend to be quiet whereas fruitcake haters tend to be loud, but most fruitcake haters I know have never had good fruitcake (and some have never had any fruitcake at all). So it seems that makers of fruitcake either must either hide their wares under a bushel (no!) or share them with evangelical fervor. Thus, I have decided to become an evangelist for fruitcake. Because everyone (especially my brother-in-law who requires more prayer, for he has yet to refrain from making disparaging remarks while the rest of us groan and ask for more) needs to know how wonderful it is.

Taking the Long View in a Life of Hospitality

When visitors come into the well-supplied kitchen of our home, The Art House, with its 60” Wolf range and side-by-side refrigerators, they often rightly ask, “Do you like to cook?” I almost always stumble over a simple yes or no answer. After living most of my adult life feeding hungry people, I am very interested in food and cooking. But the interest has come alongside the necessity. Cooking has been unavoidable, a skill developed with use. Thankfully, I was inspired early on to see the kitchen as a wholly creative and meaningful place to work, so I have leaned into all the need with an imagination formed by those ideas.

With Bread

Company. Campaign. Champagne. Champion. Companion. Familiar words that sound so alike because they all spring from the same medieval French and Latin roots. “Com” = “with” and “Pan” = “bread.” “Camp” (champ) = “open country or field.” These words are cousins in etymology and function. To be a companion is literally to share bread with someone. To share bread with someone is to keep their good company. To keep their good company is to be their champion. And to be their champion is to be their defender, to walk among them and eat with them.

In my letters I tell him, “I wish you were here so I could make dinner for you.” I daydream about how when he is released, eight years from now, I’ll have mastered new cooking skills and will prepare him whatever he wants, however much he wants. I imagine I’ll hold a spoon coated in sauce or frosting up to his mouth and say, “Here. Taste this.” And he’ll close his eyes and taste it and then smile, like we were in a movie or something.

In my letters I tell him, “I wish you were here so I could make dinner for you.” I daydream about how when he is released, eight years from now, I’ll have mastered new cooking skills and will prepare him whatever he wants, however much he wants. I imagine I’ll hold a spoon coated in sauce or frosting up to his mouth and say, “Here. Taste this.” And he’ll close his eyes and taste it and then smile, like we were in a movie or something. We lined the jars on the familiar countertop, but first things first: blanching and cutting the tomatoes. It takes some waiting, I discovered, but only after scalding my fingers — too impatient to let the water cool down. When I asked Grandma how she knew how much salt and sugar to add to the jars, she looked at me and said, “I do it that way because that’s what my mama always did.” There is no written recipe, only paying attention.

We lined the jars on the familiar countertop, but first things first: blanching and cutting the tomatoes. It takes some waiting, I discovered, but only after scalding my fingers — too impatient to let the water cool down. When I asked Grandma how she knew how much salt and sugar to add to the jars, she looked at me and said, “I do it that way because that’s what my mama always did.” There is no written recipe, only paying attention.Counterclockwise: Keeping an Open Door in a Timekept City

The mechanical clock, first introduced in Benedictine monasteries to regulate the hours of prayer, was perhaps the true starting point of the industrial age. Timekeeping exchanged the imprecise rhythms of an agrarian world, sunrise and sunset, feeding and milking, planting and harvest, for autonomous, mathematical regularity. It was a boon for business, enabling one to promise and deliver products at an exact time.

But the invention of the clock also had unintended consequences. Time became a currency: trafficked, not received. We make time, save time, spend time, waste time.