Heading Home

“When you arrive at a fork in the road, take it.”

My dad loves baseball. From as far back as I can remember, he’s been a Yankees fan. He tells me he was a Brooklyn Dodgers fan until they broke his heart and moved to the West Coast. That was the 1950s and long before I knew him. His grandfather was a Yankees fan, and his parents are Yankees fans. Naturally, the man I chose to marry is a Yankees fan. But I don’t really remember anything about the Yankees before their comeback year of 1996. With a new manager, Joe Torre, who had never won a championship in his thirty-two-year career as both a player and a manager, the Bronx bombers began to live up to their pinstripe glory once again, winning their first world series since 1978. We followed every single game.

We didn’t own a television in 1996. When our third child was born in March, a few weeks before baseball spring training and a couple months before my husband completed his bachelor's degree in education, we were paying our bills with his substitute teacher income. We had no health insurance, no vacation time or sick pay, and made ends meet by picking up extra work cleaning houses. We’d put all our hopes in a college degree landing him a teaching job in the fall. Evenings in our second-floor apartment, after we put our two sons to bed, we’d tune into the game on our radio. While I sat on our hand-me-down sofa to nurse my daughter, Brian sat across the room writing résumés on our clunky IBM personal computer. It doesn’t take a therapist to figure out that we’d associated our own underdog story to the scrappy team fighting for a win, night after night, a couple hours south of us in the Bronx.

The 1996 season introduced Yankees fans to Joe Girardi (catcher), Derek Jeter (shortstop), and Mariano Rivera (relief pitcher), among others. It’s the season we rooted for Darryl Strawberry to rise above his drug history, and he did. We worried about pitcher David Cone’s surgery to remove an aneurysm and rallied behind him when he promised to come back by the end of the season. And he did—in time to pitch a winning game in the World Series. It’s the year I discovered the joy of befriending radio announcers John Sterling and Michael Kay. Even though I’d never meet them in person, they felt like guests sitting in our living room, passing the time with warm conversation for hours each evening. We began to relish the ritual of sportscasting, loving each Yankee home run not only for the score, but also for John Sterling’s patent call: “It is high! It is far! It is gone!” Over time, he would embellish his trademark home-run call with wordplay for each player’s name. Center fielder Bernie Williams hits a run, it’s “Bern, baby, Bern!” from the announcer’s booth; first baseman Tino Martinez cracks one over the fence, “It’s the BamTino!” and so forth.

After a long, uncertain summer, we celebrated our team’s October World Series win almost as raucously as we’d celebrated the teaching job Brian received in September. We earned a salary, and the Yankees earned a championship.

Fast forward nearly twenty years, most of our circumstances had changed. We’d moved our family—which now included a fourth child, a daughter born in December 1997—to Austin, Texas, where Brian was working toward his ordination into the Anglican priesthood. Most of the time, we kept up with our home team by streaming games through our laptops while Brian wrote papers for his seminary degree. When we wanted to replicate the old days of listening on the radio, we used a phone app. By early September, each of the five years we lived in Austin, we’d be suffering full-blown homesickness. When Texas temperatures spiked above 90 degrees at the very same time our New York friends were traipsing through apple orchards and crisp, colored leaves, we comforted ourselves by hiding out in an air-conditioned house, streaming the Yankees game and baking apple crisp from produce we’d bought at the grocery store.

The best cure during those wistful years came on the days we packed up our minivan and drove north by northeast 27-odd hours out of Texas and back to our home state. Even though we could catch the games on our app, we always felt like we were in the homestretch of our journey the moment we could actually get the game on the radio.

We drove so many dark miles during those years, listening to announcers who felt like friends. In 2005, Suzyn Waldman became the third woman in MLB history to work as a color commentator on a regular basis. She persisted through all kinds of sexist criticism, including death threats, to become an icon in her own right, calling games from the radio booth with John Sterling. We weren’t thinking about broadcasting history when we’d find a game on the car radio. From the moment we heard Suzyn’s and John’s voices, thick with Northeast accent and sarcastic wit, we only thought of how close we were to the comforts of home.

On July 4, 2015, Brian and I were driving back to Texas after a week spent with family in New York. I’d cried through most of Pennsylvania, as had become the custom, recovering a happier mood about the time we passed the great lake in Cleveland. We were traveling without any of our kids this time, all at college or in jobs that didn’t allow them much leave time, which was a whole new sort of loss just dawning on us. Probably because the kids weren’t with us, we hadn’t even thought about the fact we’d be driving across the country on the day of its birthday. We’d already listened to the Yankees beat the Tampa Bay Rays with an improbable run scored from second and a slide into home base to win the game 3-2 in the ninth inning. Listening to baseball games seemed like the most patriotic way to spend our travel day, though, so we then picked up the Reds vs. the Brewers. About 9 p.m., we drove I71-S through Cincinnati, past the city’s Great American Ball Park just as the fireworks began. The Reds lost to Minnesota, but everyone was celebrating the USA. Driving through that corridor of red, white, and blue sparks lighting up the Ohio sky helped us settle our hearts toward our new home.

“You’ve got to be very careful if you don’t know where you are going, because you might not get there.”

Our daughter Natalie dropped out of college this past January. She’d set her heart and soul on a plan that did not work out the way she’d hoped. The day after Brian left her at her empty dorm at the end of Christmas break, she called to tell us she needed to come home. We told her we needed to sleep on it because we were trying to be responsible parents, but in my heart I was secretly, selfishly elated. A couple of months before her freshman year began we’d moved from Texas to Connecticut where Brian was called to pastor a church. Natalie had moved with us, in theory, but she’d spent her summer working at a camp and visited our new home only long enough to do her laundry and re-pack her suitcase. All semester, when new acquaintances asked her where she came from, she’d answered something different: upstate New York, Austin, Connecticut, Philadelphia.

Her heart was searching for home.

Meanwhile, I’d tried to remake a home in a house that didn’t belong to us, for a family who no longer lived with us. In our preparation to move, I’d insisted on finding a house with four bedrooms, imagining lots of visits from the kids still living in Texas and weekend drop-ins from our daughter in Pennsylvania. We used the rooms a couple of times, filled every bed plus an air mattress over Christmas, and now, in early January, the house felt overwhelmed by its emptiness. To save money on heating fuel, we closed off two of the bedrooms until we needed them and left Natalie’s open, just in case. We knew she was struggling to get her footing at school, but we were rooting for her to stick it out another semester.

It didn’t take much for her Dad to hop back in the van and drive three hours south to collect her and all the dorm-room supplies we’d helped her select in late summer. None of us knew what the next step would be, or should be, for Natalie. She landed a couple of part-time jobs, slowly unpacked her bags, and watched a lot of sitcoms from the couch. We tried to help her navigate, offering advice when she asked, praying for her when she wasn’t looking, but mostly, joining her on the couch. Evenings, Brian made popcorn on the stovetop the way his Grandma used to make, and we laughed hard at dumb television shows. Natalie’s spirits began to lift right around the time the New York Yankees reported to Florida for spring training. She’d tell you it all started while she was watching Aaron Judge’s guest appearance on The Tonight Show. She watched this shy, 6’7” kid participate in a hilarious segment and immediately set the DVR to record all of the upcoming Yankees games. She’d wait until Brian was home so they could watch every single inning together, a nightly father-and- daughter liturgy that she will never forget. When the team won, she had someone to root for at a time she didn't know how to root for herself. When the team lost, she had a tangible target for her disappointment. Either way, she had her Dad with her for every pitch.

Watching my husband and daughter reminded me of something historian Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote in her memoir, Wait For Next Year, about the incalculable role baseball played in her relationship with her father. Around 1950, on the occasion of her seventh birthday, Doris’s dad gave her a red, spiral-bound scorebook and taught her how to track every play of the game. She would painstakingly pencil in each move of the daily Brooklyn Dodgers game to recount to her father when he returned home from work in the evening:

“Well, did anything interesting happen today?” he would begin. And even before the daily question was completed I had eagerly launched into my narrative of every play, and almost every pitch, of that afternoon's contest. It never crossed my mind to wonder if, at the close of a day's work, he might find my lengthy account the least bit tedious. For there was mastery as well as pleasure in our nightly ritual. Through my knowledge, I commanded my father's undivided attention, the sign of his love. It would instill in me an early awareness of the power of narrative, which would introduce a lifetime of storytelling, fueled by the naive confidence that others would find me as entertaining as my father did.

So too, for approximately 162 games this season, my husband and daughter become reacquainted around the drama of baseball. The final score for each game is about as unpredictable as the plans we make for our lives, but the daily rituals are the same—one pitch at a time, day in and day out, never alone, always part of something bigger than ourselves, something that began before we did and will end after we are gone. This is the dailiness of baseball, and of life. There are plenty of other metaphors for life, other than this one, but for Natalie right now, baseball with her dad is the one that counts. Much like the athletes she roots for night after night, we are celebrating every small effort that inches her closer to home.

“Love is the most important thing in the world, but baseball is pretty good, too.”

On July fourth this year, Brian and I visited my grandparents. We asked them if we could come over to their assisted living apartment and watch the Yankees game together because we knew they’d be watching: they follow every game even though my 90-year-old grandmother has lost most of her sight and much of her hearing. During each game, my grandfather, who’s a bit older but less infirm, sits in a recliner chair shoved up to the screen of their 20”-television in order to provide play-by-play commentary for my grandmother sitting in her recliner a few feet away.

By the time we arrived, the game had already begun, and my grandmother called to me at the front door to sit in the chair holding my grandfather. I can’t be positive, but Grandpa seemed relieved to pass the job onto someone else. At first I declined her offer, laughing that Brian or my dad would do a much better job calling the game, but this was before I realized she was more instructing than inviting me. Obediently, I took my seat. At this point the Yankees were trailing the Toronto Blue Jays 4-0, but we hoped our pitcher C. C. Sabathia would hold the visiting team off long enough for our big bats to make up the difference.

I tried to humor my Grandma, mimicking my favorite radio announcer calls, but was almost immediately stumped when she asked what inning we were in. For all my years of listening to games, I’d paid little attention to the meaning of the scoreboard shorthand. I squinted my eyes to the tiny box in the corner of the small screen and confidently stated, “We’re in the top of the fourth inning.”

“Are you sure about that?” Grandma asked, incredulously peering through her thick glasses in the general direction of the screen. Of course I wasn’t sure.

“Umm . . . Brian? Dad?” I’d caught them mid-conversation on some sports-related debate, and they affirmed my answer without taking the time to check the scoreboard for themselves.

Grandma wasn’t buying it. “How can that be since the home team is up to bat?” Out of all of us, it was Grandma who was really watching the game.

May I be so attentive when I’m 90.

The Yankees never rallied that game, much to my grandparents’ disapproval. At one point, my grandfather—who’d been silent most of the game—shouted at the TV set, “Open your eyeballs, you dummies!” This was the loudest, crossest epithet I’ve ever heard him utter. No matter how disgusted they get, they won’t stay away from the next game. Or the one after that. As long as they have breath, my grandparents will be rooting for the New York Yankees.

And why not? Baseball is the embodiment of hope—a sense that is depleting with each new ailment my grandparents suffer. Every batter that approaches the plate is like a new mercy with the potential of fixing all of the previous wrongs. Baseball is the game for the most moderate of hopefuls - if the batter hits the ball at least one out of every three attempts, we call him great. That’s the sort of expectation my grandparents have lived in their lives, never hoping for too much, but working their hearts out to stay above too little. Now, as their physical capacity to enjoy life fades a little bit each day, they’re hoping for a little relief from nine innings of possibilities.

That’s what our country has always expected from its national pastime. We don’t need every hit to be a run, but we do need the players to keep showing up to bat, and the games to keep going on no matter what crisis is headlining the daily news. in 1942, around the same time my grandfather and his two older brothers were called to military service, the baseball commissioner was uncertain about the appropriateness of baseball in the aftershock of Pearl Harbor. President Roosevelt responded "Let's play ball!" and the players that didn't head to Europe or Japan gave our nation something to cheer for while we waited for all our kids to return home from across the globe. In the fall of 2011, the whole country held its breath when President George W. Bush walked to the mound to throw out the first pitch in Yankees stadium after the Twin Towers came down. He threw a perfect strike, and we all felt a bit more assured that we could go forward into the uncertainty of post-9/11 life. The New York Mets offered their entire stadium to give the Tampa Bay Rays a home away from home following Hurricane Irma last month — this just a few weeks after Tampa Bay had offered the same to the Houston Astros reeling from Harvey.

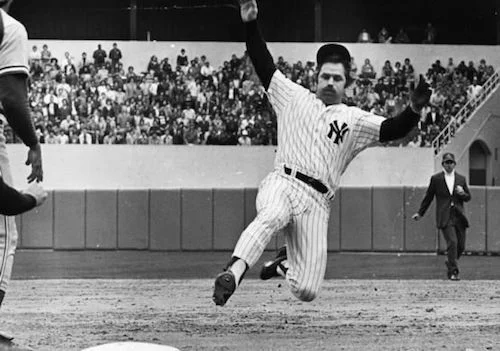

The season of 1979 tells one my favorite stories of the healing powers of baseball. On August 2, the Yankees’ catcher and beloved team captain, Thurman Munson, was killed in a freak airplane accident. Four days later, the entire team attended his funeral in Canton, Ohio, even though they were in the middle of a four-game series with the Baltimore Orioles and were scheduled to play in New York that night. Two of the players, Lou Piniella and Bobby Murcer, gave tear-filled eulogies at the funeral. The team then flew back to New York and took the field, emotionally spent and still in shock at the loss of their teammate. The team then flew back to New York and took the field, emotionally spent and still in shock at the loss of their teammate. No one expected them to beat Baltimore that night, and the prediction seemed to be correct when after six innings the NY lineup had yet to score against the Orioles’ four runs. That’s when Bobby Murcer hit a home run to bring in three runs. The Yanks were in the game, then, but still losing until the last up of the last inning when Bobby Murcer accomplished his finest career moment with a single into left field that brought in two runners and won the game for the Yankees. That morning, Murcer gave the eulogy at his dear friend’s funeral, and in the evening, he hit a baseball hard enough two times to bring five players over the home plate and give the grieving New York fans something to cheer about.

My grandparents have their own stories of grief, loss, and celebration—each moment embedded within the daily, ordinary lives they’ve carved out for 90-plus years. From her rocking chair, Grandma prays for each of her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren by name every single morning, and every single evening during baseball season, she roots for a team to round the bases to cross home. I wonder if one devotion might help form her for the other, both requiring hopeful acts of attention. Like on August 3, 1979, the first time the Yankees took the field after the announcement of Thurmon Munson’s death, when the 50,000 fans in attendance gave their missing catcher a twelve-minute standing ovation after the national anthem and a moment of silence. The starting Yankees players just stood in the field looking toward the place where their captain should have been behind home plate, caps held over their hearts and shoulders shaking with sobs.

So when I watch baseball, I think about my grandparents, and my daughter, and all of us longing for home. Getting up each morning, taking our best swing at what life throws our way, holding on by the sheer grace of the few times we get it right. And I think about promises we are given for our endurance, and our running and not giving up hope. And I imagine something like that stunning ovation cheering us on, ready to welcome and comfort us from all our lost and wandering ways.

It is a good hope, and it is enough to keep me headed home.