Finding Voice

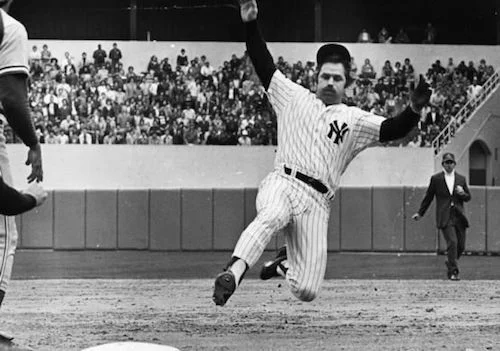

Photograph by Barbara Lane

Over the past year or so, I’ve discovered a love for jazz music.

I’d listened to it before—because a lot of people who I thought were pretty cool seemed to like jazz and I thought that I probably should as well, even though it sounded like barely contained chaos and stressed me out a little bit. But now I’ve really begun to enjoy it. I’m not exactly sure what changed except that I made a friend who shared with me his love for vinyl and I played summer babysitter to his record player and extensive vinyl collection: Miles Davis, Chet Baker, John Coltrane, Clifford Brown, Billie Holiday, Thelonious Monk, and others—more than I could take in over a summer that flew by in a blur of vinyl-lilted breakfasts and evenings on the couch with a bourbon, listening to Miles Davis’s rendition of Porgy and Bess or Billie Holiday’s 1956 concert at Carnegie Hall. Within the fantastic blur, however, there are moments of slow contemplation and true leisure, delight—moments as clear and precise as the movement of the stylus through the grooves of a record in my tiny, but growing, collection.

When I place a record on the turntable, something in me slows down. It simply will not do to continue the multitasking that consumes most of my days and some of my nights. This is not background music for grading; it is an experience. I must listen. And as I listen, the experience threads its way into the busyness of my everyday. As I listen, the crackle and hiss of the turntable’s voice lets me into the wild soul of the music.

Suggestion: Pause from your reading to listen to the song threads. Really listen. Savor the sounds.

* * *

Thread: Chet Baker, “Broken Wing”

The scratch and tap of pencils filled the room, punctuated by miniature drumbeats pattering through a set of headphones. I was substitute-teaching a high school art class. When I’d arrived that morning, the teacher’s scrawled instructions were waiting on the desk: Have them write a two-page essay—“If you were to create a self-portrait, how would you reveal yourself and what materials would you use?” After a collective groan, my students set about their task. I drifted between desks, answering questions along a trail of pencils poked into the air. With a distraught sigh, Taryn raised her hand. When I reached her desk, she looked at the floor and shuffled her feet. “I dunno what to write,” she whispered, fighting tears. “Besides, nobody’s gonna read this shit.”

* * *

Thread: Miles Davis, “Bags’ Groove”

I sat down with Taryn and talked about why she didn’t want to write. Her experiences of rejection, invalidation, and abuse were the heartbreaking foundation of a deep-seated contempt for herself and for the world that wouldn’t allow her to be freely in the world. She did eventually write the assignment, but only after I promised to complete the assignment myself and share it with her the next day. I didn’t heal her every wound or solve any major problems, but we met in a deeper-than-usual place that I hope made some sort of difference in that young woman’s life.

There’s this thing I’ve been trying to articulate ever since that day I encountered Taryn. I know that it has something to do with vocation and voice. And I know it’s something that I have found, with very few exceptions, matters deeply to my students—whether they are in high school, in their first semester of college, or returning to school after a life took them away for many years.

It was that day with Taryn when I first encountered a strong sense of my vocation (understood in light of Frederick Buechner’s definition: “The place God calls you to is the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet”). I experienced, in a very real way, how my particular aptitudes met the needs of a particular moment in a way that I could voice, and by exercising my voice, I met another human being in a place of vulnerability and meaningful connection—in a place of truth. That movement from a typical teacher-student interaction to a place of meaningful connection and truth happened in the context of voice.

I’ve come to understand voice in two ways. The first is practical and embodied. Voice becomes visible in the many ways we go about giving expression to the truths that would otherwise sit or rot silently inside us. Writing is the particular modality I’ve dedicated myself to, but there are countless ways we express truth. Some speak their truth in powerful rhetoric. Some paint or draw or sculpt theirs. Others sing or dance or play an instrument to the rhythm of the realities they long to express. The second way I understand voice is more theoretical and therapeutic. Voice is a person or group’s sense of agency, developed as they feel as though and see that, in fact, they can affect change in their own lives and in the world around them (I gained this understanding in part from a paper-in-progress presented at Northern Arizona University in April 2017 by Dr. Kym MacLaren: Agency and Self-Actualization: Lessons from Anorexia Nervosa). Where these conceptions of voice meet with my understanding of vocation—this is the thing I want so much to articulate. It’s a living, moving reality that’s difficult to stick words to—surely, at least in part, because the thing I’m trying to give voice to is voice itself. It is voice; it is articulation; it is vocation.

* * *

Thread: Duke Ellington and John Coltrane, “The Feeling of Jazz”

So now I love jazz. I listen and where, before, I heard only loosely contained chaos, I now hear freedom and wildness and voice. The more I listen, the more aware I become of the wild soul of the music and how intricately it braids itself with the expertise of the musicians who have given a lifetime of practice and discipline and passion to their craft—the sheer volume of time they’ve given to finding a voice in their instrument, honing that voice, and sending it out into the world.

The concept of voice seems particularly present in jazz. Common instruments—I’m thinking of the trumpet, trombone, and saxophone in particular—possess inherently vocal qualities and are often played in a way that enhances that quality (through the use of mutes, for example). But even the drums, piano, and bass are played in such a way that lets me sense the cadence of emotion, thought, and breath—and often more than a little sass. Each instrument, no matter how seemingly minor, is given its moment in the spotlight. I first saw this last year when I saw Branford Marsalis perform in Phoenix (beauty happens even in the sprawl). Most of the audience was there to see Marsalis, yet most of the performance time was given to the drum, piano, and bass players—and their voices were breathtaking. A hypnotic cycle: rounds of solos punctuated by audience applause followed by another round of the collective voice of all the instruments. Boldness and generosity embodied.

* * *

Max Roach and Clifford Brown, “Jordu”

“Why are you here?”

I pose this question to my students at the start of every semester and allow silence to fill the room as they stare back at me, uncertain of how they should direct a response.

“Do you mean why are we at this university?” one student asks.

“Sure,” I say. “Let’s start there.”

Most of my students are freshman, so where to go to college is the big life decision most of them have recently made—the transition they have just completed. Most of them have just left home for the first time. Their families are in Phoenix or Tucson, Los Angeles or New York, Nepal, China, Austria, and too many other places to count. Most of them are living on their own and experiencing autonomy for the first time, and where they are doing that is significant to them. So we talk about their reasons for coming to NAU. For some it’s closer to home than the other places they were accepted. Others were offered scholarships. Still others made it onto the football, hockey, or dance team. The reasons are varied and most of them respond to the question with excitement and pride.

“So why are you here?” I ask again.

Another student asks if I mean to inquire about the degree programs they’ve chosen, and a wave of anxiety washes over the room. Most of them have already declared their majors. A few of these feel certain about the decision; most are uncertain or are terrified they made the wrong choice. The ones who haven’t declared a major sink down in their seats and hope that I don’t ask. The implicit assumption is that their major will define them to the world and to themselves for the rest of their lives and one wrong move here will make or break them. They don’t yet know that I hold three separate degrees in three very different fields because I couldn’t make up my mind (business and accounting) or I let someone else make up my mind for me (seminary) or I finally found that what I’d love and be good at might never make ends meet (teaching and writing). They don’t yet know how much my life was enriched by making these so-called mistakes. I steer the conversation away from their majors because I don’t believe that it really matters how well they adhere to our rigid labeling system or where they place themselves within it.

“Do you mean, like . . . why do we exist?” The student who asks this question is the one I expect will remain unafraid as the semester goes on to move class discussion to a deeper and more meaningful level. Sometimes it’s the driven A-student who is hoping to get into the same sorority her mother was in; other times it’s the stoner C-student sitting at the back of the room. There are no predictors for curiosity or depth or pending existential crisis. This is where I sit back and let the conversation happen. They find their own way from here to the concept of vocation—how who they are and what they do might intersect with the needs of world around them. Students majoring in engineering and computer science majors point out that the ways their minds work will enable them to better infrastructures and technologies; students majoring in nursing are clear in their desire to be present to the world’s pain; business students declare their aptitude for organization and entrepreneurial endeavor; students in the humanities tend to struggle most in articulating how their particular passions will meet a need in the world, but they know it relates somehow to history and words and beauty. The undeclared students respond with the most fear (because they haven’t yet filed themselves into an educational category like they are supposed to) and with the most curiosity, which is perhaps the very aptitude they bring to the world.

“So . . . ” I ask once more, “why are you here? Why are you taking my class?”

I teach a four-credit-hour composition course that is required for almost every undergraduate student attending my university. Naturally, then, they all stare at me for a good long moment as they contemplate 1) The possibility that I may not be aware of the fact that they are only there because they have to be, and 2) Whether they should say that out loud. Silence fills the room again. One brave soul finally speaks up: “Because . . . we . . . have to?”

A minute or two into a discussion about the university’s motivation for requiring them to take a composition course, we connect this requirement to their desire to be successful in college and, eventually, in their chosen careers (however many of those they end up having). Finally, one student makes the connection between what we’ll do a lot of in my class (writing) and our earlier conversation about vocation: “Wait, so does being a better writer make us better at doing whatever we do to help the world be better?” The student who makes that connection is the student I expect will gain the most from my class and from any class they take. This is a student who forges a path between the impositions of education and their own development as a human being striving to live meaningfully in the world. Often, this is a person who has already begun to discover their voice, who longs (or has already begun) to unlearn the lessons taught by a cruel world that told them they had nothing important to say and that, even if they did, no one would listen.

I’ve been surprised to learn how many of my students have been told that they are bad at writing. Somewhere between their first words as infants to writing papers in high school, someone communicated to them that their articulation of the worlds in and around them was inadequate and, in so doing, scarred their belief in themselves as beings who give voice to those realities. So they tweet and Snapchat into a void, desperate for someone to like what they say or acknowledge what they see, relieved to offer their articulations up to social medias that accept their misspellings, incomplete sentences, comma splices, and hashtags. Regardless of their particular passions and aptitudes, regardless of their chosen or not-yet-chosen majors, regardless of where they are from or why they are at this particular university, they want to be heard.

That, I tell my students, is what I want them to learn in my class. That they have a voice. That what they have to say matters. Of course, we will practice ways to make our thoughts more readily accessible to audiences that have the capacity to act on what they say. We will practice adding to current conversations with meaning and substance rather than just making noise. We will talk about how to take a deeper dive into the content of our thoughts and beliefs. We will learn to identify the ones that deserve and demand articulation and to distinguish them from ones that add to the noise of a very wordy world. We will wonder together about the difference between appreciating small things (like the precise color of the flowers outside our building that died in the late frost) and blathering on about insignificant things (tweets that announce to the world our every moment while preventing us from being present to any one of those moments). Grammar will come in to play. MLA or APA formatting. Works cited and in-text citations. We’ll do all of this and more. But above all, you have a voice.

* * *

Thread: Billie Holiday, “Summertime”

Somewhere between (or underneath?) deciding on a major and tweeting about their new roommates, there is the intersection of vocation and voice. This intersection is small. It’s a little underneath and over to the left or right of our dailiness. For me, it’s in proximity to my job—getting up and going to work every day, answering emails, lesson planning, slogging through the piles and piles of grading. I find it when I get underneath the busyness of my work to find the passion that motivates that work, the difference that I might make in the world, and over to the left or right of the noise of the day to articulate myself with greater authenticity and creativity and precision to the world around me. For you, the specifics may be different, but the textures are the same—it’s underneath and to the left or right of what pays the bills and the conversations and goings-on that fill your everyday.

Small though this intersection of vocation and voice may be, it is fit to burst with the power it contains. I felt this power that day with Taryn. I see it flash in my students’ eyes when they begin to see the connection between what they do and who they are and what difference they might make in the world. I hear it in the wildness and discipline, boldness and generosity of the crackle-and-hiss voice of my record player. I don’t know how to give perfect voice to this reality, but it’s there. I know it’s there. And I believe that the most important work we have to do is in found in living the questions (thank you, Rilke): Where is that intersection of voice and vocation is for me? For you? For the children and young adults whose lives our voices might affect? How can we come to a greater embodiment of voice and vocation? How do we find out our own crackle-and-hiss voice? Who can we join in a collective voicing of truth?

Photograph by Barbara Lane