Academy of the Observant Life

An excerpt from a forthcoming memoir by Charlie Peacock.

Ambrose, the Bishop of Milan in the 4th century, was a preacher/singer like Bono is today. His most famous student was Augustine, the world-weary saint who wrote a series of thirteen books called Confessions. In book nine Augustine remembered the music of his teacher this way:

The tears flowed from me when I heard your hymns and canticles, for the sweet singing of your church moved me deeply. The music surged in my ears, truth seeped into my heart, and my feelings of devotion overflowed, so that the tears streamed down (Confessions 9:6-7).

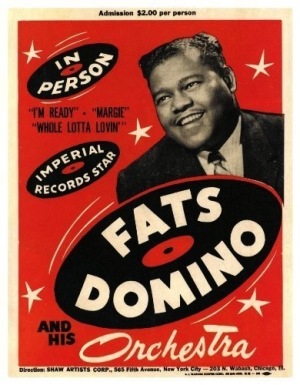

I once met a contemporary Ambrose on a trip to New Orleans, just a year before the tragedy of Katrina — I’ll call him the Bishop of Transportation. I was on the move visiting musician/actor brothers Jonathan and Richard Jackson on the set of Miramax’s teen-horror film Venom, a “straight to DVD and don’t pass Go” release. (If you watch the current television show Nashville, then you know Jonathan. He plays “dead sexy East Nashville hipster” Avery Barkley.) After our rainy visit, Ambrose, a cabbie, ferried me from the French Quarter to the airport. He talked. I listened. He was a street philosopher, a PhD with tenure in the academy of the observant life. Ambrose explained that Al Capone’s second-in-command once managed Louis Armstrong. News to me, but it made a certain kind of jazz sense. He also knew a lot about Dr. John, Pinetop Smith, and Professor Longhair. He told me that Fats Domino (born Antoine Dominique) was still living in his original neighborhood, the Lower 9th Ward — “built that big house, you know.”

Three days after Hurricane Katrina the whereabouts and fate of Fats Domino was still unknown. Yet because I met Ambrose in New Orleans a year earlier, I understood the context for the unfolding story of Katrina. Finally, Fats and other family members were rescued by boat, leaving his mansion of pink, yellow, and lavender to the dark fate of mud, mold, and ruin.

Eighty-one-year-old blues icon Clarence "Gatemouth" Brown didn’t fair as well. He lost his home in Slidell, Louisiana, and then his life in Orange, Texas. Though Brown was already seriously ill with lung cancer when he evacuated Slidell ahead of Hurricane Katrina, it’s believed that stress hastened his death. The singer’s agent Lance Cowen told the newspapers: "He lost everything except his Firebird guitar and a fiddle.” My friend, and sometime music collaborator, Sara Groves, took her tour bus to Slidell filled with diapers and formula. A young mother herself at the time, it was her way of making neighborly love real. Sara described the area along the east shore of Lake Ponchartrain as, “Unbelievable. The houses on the right side of the road were on top of the houses on the left side of the road. A mile inland there was a houseboat in the median of the highway.”

That Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown would have to cross the Sabine River from southwest Louisiana to die in the east Texas town of Orange was of great interest to me. This short trip across the river of cyprus has been common for people of color for centuries, going back to before the Louisiana Purchase and the establishment of the neutral zone, or no man’s land. My own family, the “fabulous Ashworth clan,” zig-zagged between the neutral zone on the Louisiana side and Jefferson County, Texas.

In case you’re just entering my story, Peacock is a stage name. My great-great-great grandfather, Tapley Abner Ashworth, is buried in Harris Cemetery in Orange, Texas. You can read in books and congressional records about Tapley Abner and his brothers William, Aaron, and Moses — “free persons of color,” later called Redbones. While the men were honorable citizens of the Republic of Texas, and considerable landowners, there came to be An Act Concerning Free Persons of Color which required all free persons of color to leave the Republic within two years. The Board of Land Commissioners and various citizens of Jefferson County petitioned the Senate and House of Representatives of the Republic of Texas to exempt the Ashworth families because the brothers were “industrious and orderly” — men who would never have been forced to leave “had there been no taint of blood in their veins.” Most notably, the petition informed the Senate and House that the Ashworths came by their color through “great and embarrassing circumstances.”

In 2005, during the aftermath of Katrina, the great and embarrassing circumstances belonged to the US government. And once again, race, color, status, and land were all up in the mix. Just as the governing powers didn’t know how to deal with such things back in the days of the Louisiana Purchase, they didn’t know any better in our day either. All things surrounding Katrina went from bad to worse quickly. At the time of our conversation, Ambrose the cabbie had no idea the fate that awaited him with Katrina. None of us did. I hope he lived to tell. He did know some things of great importance though, telling me “music’s good for the soul.” I agreed, thinking he had the elder Ambrose, and surely Fats Domino on his side with words like that. Music surging, truth seeping — that’s jazz right there.

Along with our love of music, the cabbie Ambrose and I had grandchildren in common. We chatted the little ones up with excitement and broad, toothy smiles. The irony of conversing with a stranger is that your individual lives always look very different and personal, but then you strip away the nuances to find a common likeness buried inside of diversity. Take away money and geography and we’re all just flesh and blood and soul. We’re all dealing with sin and forgiveness, love and hate, glory and shame. The big ideas remain. Life creates another day of history and the babies keep on coming. People dream their dreams. The young grasp at reinventing the wheel and the maturing masses learn to let go of such reinventions one breath at a time. In the book Mexico City Blues, Jack Kerouac wrote, “I wish I were off this slaving meat wheel and home in heaven, dead.” Sacramento guitarist and friend Pat Minor used to quote this verse often. Pat smoked unfiltered cigarettes like he was playing the blues and could go jaw to jaw with Jay Leno’s jaw should the need arise. Pat had a special way about him when he encountered absurdities or extraordinary foolishness. Unique to him, Pat’s six-foot-plus frame would take on the shape of a question mark. One eyebrow would rise to an Olympic height, and his smile would wrinkle outward into the world, his head bobbing as if on a spring. Then with a slow, exaggerated tone he’d ask anyone who might be listening, “What were they thinking?”

His was the art of being human, of being Pat. For twenty-seven years Pat worked at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento. He hung the shows, painted the walls, and finessed the lighting so that art might have its day. Pat once described a Persian antiquity as, “So light, it felt like a thought.”

With wisdom he added, "You always have to have reverence in your hands for everything."

The slaving meat wheel is real. People experience the repetition of every kind of enslavement everywhere and in everything. On this subject, Kerouac’s verse is spot-on. I part with him over death and heaven, though. I don’t want to be dead in heaven or dead anywhere for that matter. I’m hoping to be counted among the brave poets who stay alive on earth and in heaven. That’s my quest. Maybe this is what Paul of Tarsus was getting at when he wrote this in Philippians 1:

If I am to go on living in the body, this will mean fruitful labor for me. Yet what shall I choose? I do not know! I am torn between the two: I desire to depart and be with Christ, which is better by far; but it is more necessary for you that I remain in the body.

A quiet peace filled Ambrose’s cab and I remembered something beatific from the day before. I was shuffling down Canal Street when I heard some mad character ask, “Anybody know where I can get my watch repaired? I’m a hustler and I gots to have my watch.”

I love it. First, there’s the transparency: “I’m a hustler.” Second, modernity has so had its way with the western world that even the lives of the street hustlers are dictated by the clock. What we all need is island time, like on Whidbey Island in Puget Sound. I spent a few nights there and woke one morning needing a new book — a casual read, an adventure, or spy novel. I found the bookstore closed at 10:30 in the morning. The explanation? Island time. Shops are open from 11–5 with a long lunch in between. That’s a hustle, too — one of privilege and the freedom of an open, unhurried life. Many of us are working, hustling, hoping to get that kind of life for ourselves. And while we are up to it, others are doing an altogether different hustle. Like the fellow that sat across from me on my flight home to Nashville from New Orleans.

He was an American soldier, a traveler of the war in Iraq. He’d lost his original birth condition. Both legs were gone, replaced by prosthetic devices so high-tech you’d think NASA had designed them (maybe they did). He wore it all proudly, talking about two appearances on Fox News and dragging the then-controversial Michael Moore and Fahrenheit 9/11 through the mire. The soldier had bad days, too. That’s what he told his seatmate. She clearly understood in ways I couldn’t. Her right hand was the pattern of all flesh, but her left hand held a surprise. Fickle genes had provided her with only a tiny thumb and forefinger, and that’s it — an abbreviated hand. I stared at my tray table and wondered what the odds were that these two strangers would sit together.

Cheerily, they refused to talk defects or handicaps — that would be so 1965. Their cabin chatter was all the language of victory, of dreamy lives and positive thoughts. The soldier told the woman that Sharon and Ozzy Osbourne had visited him in the hospital — gave him some T-shirts and CDs. “They were cool,” he said. “But I don’t need Sharon Osbourne to teach me about foreign policy.”

And there you have it. There’s always something to be learned.