It is April in Paris, and I am sixteen. The grey stones shine slick with spring rain. Stripping off my jacket as I approach the bookstore, I wonder if I should also remove my shoes. This is holy ground, isn’t it?

It is April in Paris, and I am sixteen. The grey stones shine slick with spring rain. Stripping off my jacket as I approach the bookstore, I wonder if I should also remove my shoes. This is holy ground, isn’t it?

Inside, stacks of dusty books hold me in thrall. George Whitman — whom people whisper is a bastard son of Walt, a groundless rumor he may have encouraged — finds us. He is all kindness and frizzled white hair. “Do you need a place to stay?” he asks, and my breath catches in my chest as I imagine myself claiming a spot on an upstairs cot, intoxicated that I could join the ranks of writers who have stayed at Shakespeare and Co.

Of course, I am sixteen. Our mothers are around the corner. We have a very nice hotel on a quiet street in St. Germain, and only dare to dream that one day we might be starving artists. We wear our skirts and our hair long, carry journals and cameras, keep ticket stubs for scrapbooks, sign our names to a napkin from Les Deux Magots (I sign Simone de Beauvoir’s name as well).

I try — and fail — to feel at home in a beret and a scarf, but I look more like the prep school student I am than the bohemian artist I want to be. I am shamefully sure that I am too much of a good girl to ever make history. As proof of my ordinariness, my duty to stolid convention, I find myself wondering about my maidenly virtue, if I were to stay in one of those magical second floor beds.

* * *

The Shakespeare and Co. bookstore I visited in 1998 wasn’t the original, which was founded by American expat Sylvia Beach in 1918 as a lending library for English-language books, and quickly turned into a second home for writers such as James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. If you’ve read Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast, then you’ll recognize the bookstore from his descriptions.

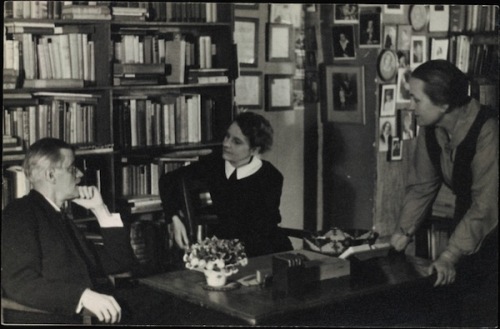

James Joyce with Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier at Shakespeare and Co. in Paris, 1920. Image courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University.

James Joyce with Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier at Shakespeare and Co. in Paris, 1920. Image courtesy of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Sylvia Beach, daughter of a Presbyterian minister from New Jersey, stocked the store according to her own taste, kept banned books available, and created a press in order to release James Joyce’s Ulysses in its entirety.

Beach’s Shakespeare and Co. closed under German occupation in 1940. (Legend has it the store closed because Beach refused to sell a German officer the last copy of Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake.) Just over a decade later, a new English-language bookshop opened in the Left Bank, George Whitman’s Les Mistral. Like the original Shakespeare and Co., it became a hub for the expat literary community, particularly Beat writers like Allen Ginsberg. In 1954 Beach told Whitman he could use the name, so after her death, Whitman renamed his bookshop Shakespeare and Co. in honor of the original.

This was the shop I visited as an adolescent, nervous about my right to even enter, sure that I didn’t belong and that my beret looked ridiculous. This was the place where George Whitman said, “Do you want to stay?” and for a half second he made me believe what I desperately wanted to believe: that I could be a writer.

Photo: Amy Lepine Peterson

Photo: Amy Lepine Peterson

It’s been fifteen years now, and I can’t be sure if my memory is quite right. Was it really George Whitman I met that day, or another shop attendant? I know I saw the second floor, but did they really offer one of those cots to me? Beyond what the photos prove was real, how much does imagination color in where memory has failed?

And even if my memory is accurate, who’s to say I understood it all properly at the time? It’s possible that if he offered me a place to stay, he was trying to take advantage of me. Or maybe I looked thin and bedraggled, truly in need of a bed and a book.

I like to think, though, that George Whitman knew that in offering us travelers one of the thirteen beds he kept upstairs, he was intentionally offering us the affirmation that we could be writers, too: that any one of us might become immortal, the next Hemingway, the next Burroughs.

* * *

It’s January in Upland. Winter here is long and cold. When I step outside, I step into silence. The wind is the loudest thing for miles, cutting across burned-out cornfields, no hedge of evergreens or buildings to protect us against its chill. The town is four square miles: one blinking stoplight, three gas stations, a college, and then a return to flat squares of farmland. When we moved here from Seattle nearly three years ago, the isolation felt like a threat, the loss of our cosmopolitan pleasures as bitter as the winter wind itself.

Paris never slept, as I found to my pleasure when I returned at 21 and took up residence in a crummy hostel. Upland, in contrast, rarely seems to wake. But you can see the stars here like you never can in Paris, and the lonesome quiet of the prairie has started to feel like a companion. Maybe even a friend.

We’ve made other friends here in the middle of nowhere: artists and potters, novelists and poets, soap-makers, gardeners, and musicians. We’ve also made friends with ourselves. I’ve taken up quilting and stargazing, and have written more essays; my husband has created an original mosaic, composed two albums’ worth of songs, and built an enormous dining room table. These days we make our own hedge of protection against the wind, gathering around that long farm table, talking about ideas, drinking a little too much, and eating for hours, as if we were at a fancy French seven-course dinner.

I threw away my beret years back, thinking it was pretentious and that I could never pull it off. But these days I find myself thinking often of Sylvia Beach and George Whitman, and of the kind of hospitality that makes art possible.

In her memoir Shakespeare and Company, Beach writes about meeting James Joyce for the first time. Joyce was new to Paris, and supported his wife and children as a language tutor. On his first visit to the bookshop, he asked Beach to help him find additional students, and he borrowed a book from the lending library. Over time, he made the shop his office, writing there on a regular basis.

A magazine in England was publishing Ulysses serially, but subscribers were shocked by its prurience, and the magazine fell on hard times. No publisher in England would touch the book, and so one day Beach simply said, “What if I publish it for you?”

My friends have novels that are too “Christian” for some publishers, but too dark, complicated, or honest for Christian publishers. Like Beach, some of them are joining together to create their own presses to help make places where the arts can flourish. I find myself wanting to join their cause, to take up the mantle of Sylvia Beach and George Whitman, even in Upland, Indiana — the unlikeliest of places.

So I listen to piano practice, and I explain how to structure an essay. I host a poetry reading and a book release party; I edit manuscripts and plot feature pieces I can write for national magazines about works of art and mystery novels created by my friends. And I’ll invite you over for dinner, like Gertrude Stein would do, and make you listen to my records and sit around my table for hours talking about your work.

I want my hospitality to tell you, quite plainly, that you have the divine spark: that you were made in the Creator’s image — that you are destined to make beautiful things as well. George Whitman’s offer of a cot to an awkward teenager said all that, years ago, and I can’t forget it.

So if you need a place to stay, we have a spare bed, and you’re the right kind of person for it. But take off your shoes: it turns out this frozen prairie in Middle America is holy ground.

Amy Lepine Peterson teaches ESL Writing and American Pop Culture at Taylor University, and spends most of her time making a home for her best-friend-husband and their two (frankly adorable) children. You can find her in the cornfields of Indiana, or online at Making All Things New.