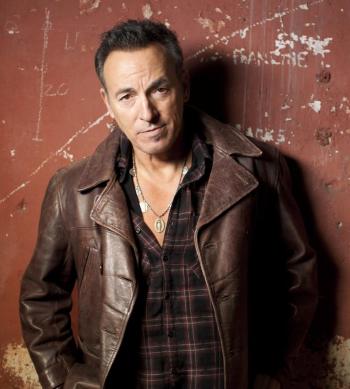

The first time I heard Wrecking Ball, the new record from Bruce Springsteen, I was driving through the middle of Kentucky on winding country roads, windows down, stereo cranked all the way up, wind whistling through my hair. I was on my way to the Abbey of Gethsemani — where Thomas Merton lived for most of his life — two days after my 30th birthday, looking forward to the time away to read, write, and reflect. With books by Merton (a first-edition copy of his memoir, Seven Storey Mountain, loaned to me by my friend Ian), Walter Brueggemann, and Wendell Berry in my bag as companions for the weekend, I found myself listening to Springsteen’s lyrics through the lens of Brueggemann’s and Berry’s words.

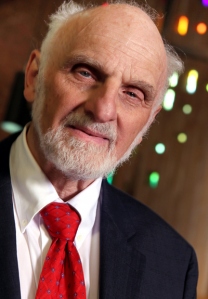

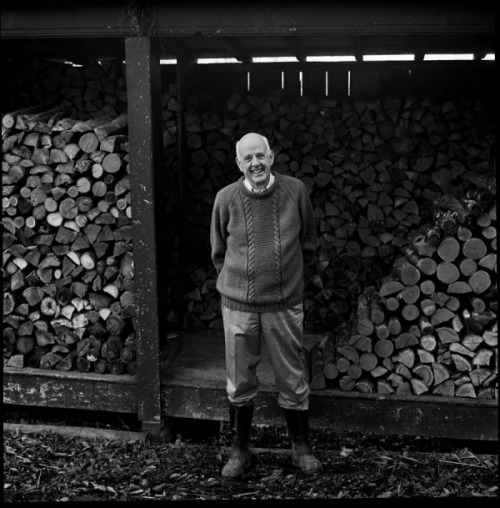

I wondered about the tension that I sometimes feel between the prophetic message of Walter Brueggemann and occasional romanticism of Wendell Berry. “God is always on the side of the poor and oppressed,” Brueggemann is fond of saying: the way he reads scripture and applies it to today’s world flows from that conviction, born from a lifetime of study and writing on the Hebrew prophets. Meanwhile, Wendell Berry’s work yearns for a simpler time and advocates a return to valuing neighborliness over consumption, and this can tend to romanticize the past. It seems willfully ignorant, or perhaps naive, about what it means to be a good neighbor in a global community, a world where your choices affect not only your neighbor across the street or the next town over, but also the individual made in the image of God who resides halfway around the world. One friend tells me that when he reads Wendell Berry, it all sounds like an old man yelling at the neighborhood kids to get off his lawn.

I wondered about the tension that I sometimes feel between the prophetic message of Walter Brueggemann and occasional romanticism of Wendell Berry. “God is always on the side of the poor and oppressed,” Brueggemann is fond of saying: the way he reads scripture and applies it to today’s world flows from that conviction, born from a lifetime of study and writing on the Hebrew prophets. Meanwhile, Wendell Berry’s work yearns for a simpler time and advocates a return to valuing neighborliness over consumption, and this can tend to romanticize the past. It seems willfully ignorant, or perhaps naive, about what it means to be a good neighbor in a global community, a world where your choices affect not only your neighbor across the street or the next town over, but also the individual made in the image of God who resides halfway around the world. One friend tells me that when he reads Wendell Berry, it all sounds like an old man yelling at the neighborhood kids to get off his lawn.

In a review of Wendell Berry’s What Matters?: Economics for a Renewed Commonwealth for Books and Culture, Alissa Wilkinson and Robert Joustra argue against the way that Berry’s writing seems to disregard the ways people seek justice outside of the model of a small community, how it can ignore the ways that the world has changed over the last hundred years, in ways good as well as bad. “This is why his poetry (and to some degree, his fiction, in its less didactic moments),” Wilkinson writes, “can ultimately teach us more than his prose. Poetry alludes where prose can merely preach.”

Still, maybe we need Berry’s prose, for in those moments where he uses the prophetic voice — a way of speaking that says nuances be damned, there’s a problem that needs to be addressed — he provides a wake-up call that cannot be ignored.

In his essay “Words Addressed to Our Condition Exactly,” essayist and novelist Scott Russell Sanders remembers reading Wendell Berry for the first time, when he was 26 years old. “Even back in my twenties,” he writes, “eager for a clear diagnosis of the world’s ailment, I realized there were more than two ways of relating to nature; yet I relished such decisive proclamations. . . . In an age of cynicism, here was an Ohio Valley neighbor who spoke with utmost seriousness about principles, virtues, and spiritual ambition. In an age of irony, here was a man who spoke with the solemn indignation of the Hebrew prophets.”

Tyler Wigg Stevenson, in his book Brand Jesus: Christianity in a Consumerist Age, argues that starting in the 60s, “The American story — which says you can shake off the bondage of your heritage — changed from a statement of possibility to a mandate: your parents’ generation cannot define you.” Indeed, Wendell Berry’s writings offer a prophetic challenge to the temptation to define oneself in this way, while Bruce Springsteen’s lyrics interrogate the struggle implicit in this statement, particularly in the context of the American Dream. They doubt whether it’s true, how you were told things would work if you followed a certain path. “My work has always been about judging the distance between American reality and the American dream — how far is that at any given moment,” Springsteen said in one interview before the record released.

While delivering the keynote address at the South by Southwest music festival earlier this year, Springsteen played the chorus to The Animals’ “We Gotta Get out of This Place” before declaring, “That’s every song I’ve ever written.” The search for a better life, built around the possibility of packing up and hitting the road, of casting off all restraints and starting a new life elsewhere is, in Springsteen’s catalogue, necessary because of the hopelessness permeating every crevice and back alley in your hometown. The future has been ravaged by the “fat cats” and those “up on Banker’s Hill” — the outside forces that destroy a community — which he writes of so often in his new album.

Wrecking Ball kicks off with “We Take Care of Our Own,” the first single from the record and the song that opened the 2012 Grammy Awards, lyrics sung with tongue firmly planted in cheek. “Wherever this flag’s flown / we take care of our own,” Bruce sings over and over in the chorus, articulating the promise of the American Dream, while the verses lament “good hearts turned to stone / the road of good intentions . . . gone dry as a bone,” and wonders “where’re the hearts that run over with mercy,” the “love that has not forsaken me.”

Wrecking Ball kicks off with “We Take Care of Our Own,” the first single from the record and the song that opened the 2012 Grammy Awards, lyrics sung with tongue firmly planted in cheek. “Wherever this flag’s flown / we take care of our own,” Bruce sings over and over in the chorus, articulating the promise of the American Dream, while the verses lament “good hearts turned to stone / the road of good intentions . . . gone dry as a bone,” and wonders “where’re the hearts that run over with mercy,” the “love that has not forsaken me.”

In the story Springsteen tells on Wrecking Ball, one finds a progression from anger — as told in “We Take Care of Our Own” and “Wrecking Ball” to, in its most explicit form, “Death to My Hometown,” anger over injustice, over the circumstances that lead to the loss of hope in the small towns of America — to hope for a better future, as in “Land of Hope and Dreams.” A song that, along with several other cuts from the album, is brimming with eschatological language. In this case, the song is built around lines from Curtis Mayfield’s song “People Get Ready”: “People get ready / there’s a train a-comin’ / you don’t need no ticket / just get on board.”

The metaphor of a train is one Springsteen has returned to frequently during his career. On the opening track of Magic, “Radio Nowhere,” a song that finds the narrator desperate for some kind of connection, he sings of “driving through the misty rain / yeah searchin’ for a mystery train,” hoping to “make a connection with you.” Important to understanding that track, I think, is the lyric change in the outro that is almost indistinguishable. “I just want to feel some rhythm,” he sings over and over before changing the line to “I just want to feel your rhythm,” with the sss sounds from the hi-hat obscuring the lyrics change from “some” to “your,” a change that has everything to do with everything Springsteen is trying to say, a line that embodies that desperate hope for some kind of personal connection, something that will make the future matter and help one make it through the night.

Last month, Wendell Berry delivered the 41st Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities. He introduced his lecture by making it clear that, “In what I will say here I speak for myself, insofar as I must take full responsibility for what I say. But I know, as the diversity of helps in the making of this lecture has informed me again, that I speak also for predecessors and allies, without whom I could not speak at all.” In “We Are Alive,” the last track on Wrecking Ball — a song built around the riff from “Ring of Fire,” one of the many musical quotations on the record — Springsteen acknowledges a similar debt to those who have gone before, to those who have fought for and served as reminders of our need to pursue justice. He reminds us of touchstones in three centuries of our history — the first major rail strike (and general strike) in our country, the death of Martin Luther King, Jr., and of the experience of some immigrants today searching for a better home: “A voice cried I was killed in Maryland in 1877 / when the railroad workers made their stand / I was killed in 1963 / one Sunday morning in Birmingham / I died last year crossing the southern desert / my children left behind in San Pablo.” All of these voices, and many more, join in the chorus Springsteen is leading, becoming part of what the scriptures call the great cloud of witnesses. “Our souls and spirits rise / to carry the fire and light the spark / to stand shoulder to shoulder and heart to heart.” Wendell Berry ended his Jefferson Lecture similarly, after enumerating the ways that we, as a country, have privileged profit and consumption over love for our neighbor: “We do not have to live as if we are alone.”

After the thunderous applause had died down, after Berry had left the stage, the night ended with the master of ceremonies thanking Berry for “presenting a thought-provoking perspective on the importance of love and affection and the social life of our country,” but he went on to say, to amused laughter from the audience, “But as an official of the United States government, I’m obligated to note that the views are those of the speaker and do not reflect that of the United States government or any agency thereof.”

“We do not have to live as if we are alone.” One would not be hard pressed to interpret a large percentage of Bruce Springsteen’s extensive catalogue of songs over the last thirty-something years as attempts to communicate the same message. The role of an artist in our world today surely includes, among other things, the task of expanding our moral imagination, a phrase first brought to my attention by American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. “The shrinking of imaginative identification which allows such things as shared humanity to be forgotten always begins at home,” Marilynne Robinson writes in “Imagination and Community,” an essay collected in her newest work When I Was a Child I Read Books.

When we become too self-focused, too intent on looking out only for ourselves, the artist can help us remember who we are and what our place is in the world. “There is at present a dearth of humane imagination for the integrity and mystery of other lives,” Robinson writes in another essay, “Austerity as Ideology.” “In consequence, the nimbus of art and learning and reflection that has dignified our troubled presence on this planet seems now like a thinning atmosphere.” It is into this climate that Springsteen’s new album has arrived, as the best-selling album in 16 different countries the week it was released. Into this “dearth of humane imagination,” he sings lyrics like these: “The hurricane blows, brings the hard rain / when the blue sky breaks / it feels like the world’s gonna change / And we’ll start caring for each other / like Jesus said that we might.”

***

After the seas are all cross’d (as they seem already

cross’d,)

After the great captains and engineers have accomplish’d

their work

After the noble inventors, after the scientists, the chemist,

the geologist, ethnologist,

Finally shall come the poet worthy of that name,

The true son of God shall come singing his songs.

—Walt Whitman, Leaves of Grass

These are the words with which Walter Brueggemann opened (and titled) his now classic work Finally Comes the Poet. In the introduction, under the heading “A subversive fiction,” Brueggemann wrote that “to address the issue of a truth greatly reduced requires us to be poets that speak out against a prose world. . . . Poetic speech is the only proclamation worth doing in a situation of reductionism.” He addressed pastors there, primarily regarding the text of scripture, but I don’t think it stretches his point too far to extend this to artists, and to the work that Springsteen accomplishes with Wrecking Ball.

When Springsteen tries to tie together the stories he tells in these eleven songs, looking forward to what follows, he turns to religious imagery, his Catholic education having shaped his imagination in ways he cannot escape. The “land of hope and dreams” he sings of on the penultimate track, the arrangement built around “People Get Ready,” is reached by a train that carries saints and sinners, losers and winners, whores and gamblers, lost souls. It carries the broken-hearted, thieves and sweet souls departed, fools and kings. It’s a place where “dreams will not be thwarted,” where, finally, “faith will be rewarded.” That sounds remarkably like the New Jerusalem promised in scripture, where everything will be made new.

After quoting a number of passages from the prophet Jeremiah, passages that promise something in the same vein as what Springsteen sings about, Brueggemann, further on in Finally Comes the Poet, wrote about what this anticipation for the day when human life is restored looks like: “When the text comes to speak about this alternative life wrought by God, the text must use poetry. There is no other way to speak. We know about that future — we know surely — but we do not know concretely enough to issue memos and blueprints. We know only enough to sing songs and speak poems. That, however, is enough. We stake our lives on such poems.”

The songs, poems, and prayers I hear from Springsteen, Berry, and Brueggemann — these lines and melodies that allude to and speak of this alternative life — are part of what keeps me returning to their work. I welcome these reminders to pursue justice, because in this way we love God, by loving “even the least of these.” The stories they tell are surely enough to stake our lives on.

Stephen Lamb lives in Nashville, Tennessee, where he works as an arranger, composer, and copyist. When he’s not writing a string arrangement or printing out another thousand pages of music for a studio session or a symphony orchestra somewhere, you can usually find him hanging out at a local coffee shop or beer garden, book or journal in hand, or enjoying conversation with friends. Sometimes he dreams about being a writer. He blogs at Rebelling Against Indifference.